Yet these are songs with a very definite and sometimes very perverse, downbeat identity of their own.

"Well, I think a lot of people are taken in by the myth that our music is totally bleak and desolate. Steve Wright, whenever he plays our records, says, I hate that band, aren't they the most depressing thing that's ever happened to music? Comments like that, people get taken in by. So I try not to let the pressure get to me, and I don't think about the consequences of a song."

Come off it. You must have expected some flak for 'Personal Jesus'?

"I thought it would get more than it did, really," he replies. "It was played all over Europe, America and England with no great trouble. The only problem was with the newspaper personal column adverts, which said 'Your own personal Jesus' and gave a telephone number.

"Imagine someone about to top themselves and they see it in the paper - my last saviour, my last chance. And it's Depeche Mode. Especially if they're a Steve Wright listener." [1]

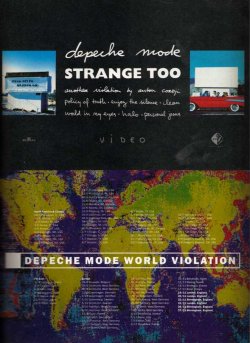

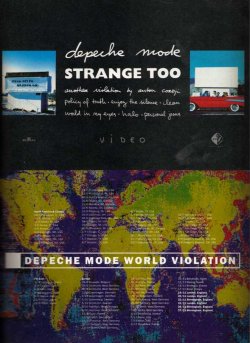

Martin's dance euphemisms aside, 'Violator' is also the album where Depeche Mode finally find out what the hi-hat button is for. For the first time, there's a strong and undisguisable House pulsebeat in evidence throughout the LP.

Yet for a couple of years pundits have been keen to stress Depeche Mode's early input into House and techno. This culminated in a fascinating piece in The Face last year, which followed the band through Detroit clubland as they met techno innovators including Rhythim Is Rhythim supremo Derrick May. May revealed that Depeche Mode's approach to sampling, and their increasing prominence in European electronic music, had given him and his contemporaries on the cutting edge of dance music plenty of ideas. [2]

The Face, however, trailed the story on its cover with the headline, Did Depeche Mode Detonate House? They didn't, of course, and no one was claiming they did. But the implication that they were claiming credit for creating the decade's most important musical form has dogged Depeche Mode ever since.

Martin Gore is sanguine about it all.

"We've been cited a lot in recent years as being this big influence on House music," he grins. "But I really think it was in our approach rather than the sound itself. In some ways we do push boundaries in music. We've always tried to be on the so-called forefront of technology, and I suppose the way we work has been quite influential. I even think it's helped, particularly in America, to change the whole format of music.

"But I don't agree that there are a lot of House references on 'Violator' - though you might say 'World In My Eyes' has a slight techno feel. And in some ways you can't help but be influenced by House - after all, it's played everywhere you go these days."

Like at Depeche Mode concerts, for instance.

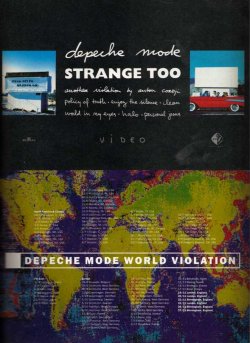

For World Violation, the band has undertaken a rolling programme of renovation on some of their back catalogue. 'Behind The Wheel', the paranoid road song from 'Music For The Masses' which they perform as an encore, now boasts a mighty House breakdown as it segues into their idiosyncratic cover of 'Route 66'. And 'Everything Counts' has been restructured techno-style to devastating effect, demonstrating Depeche Mode's growing ease with more subtle dance forms.

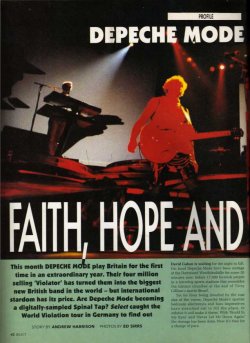

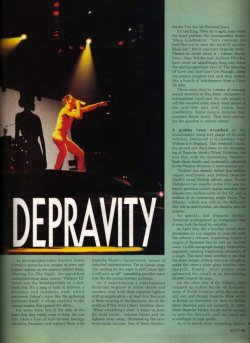

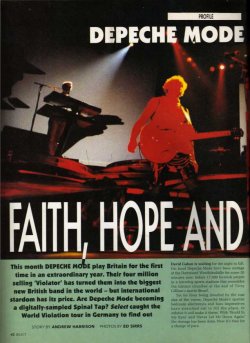

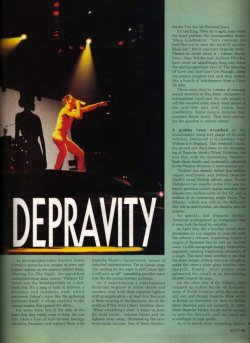

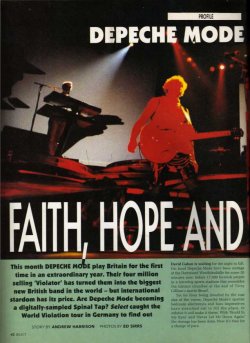

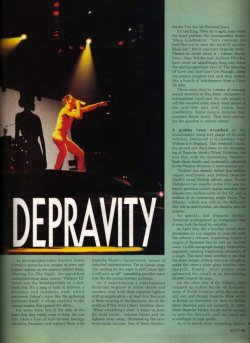

But, believe it or not, World Violation is first and foremost a rock 'n' roll show on a panoramic scale. Perhaps it's just the volume, or the shock of finding such solitary music in a context of size and excess, but in 1990 Depeche Mode win by simple power. It's not simply stunning - at times it's frightening.

'Personal Jesus' is a case in point. On record it snarls and spits, the perfect antithesis to the redundant pretty-boy image of Depeche Mode that still lingers in British minds.

Onstage the song becomes monstrous. For 17,000 German kids, David Gahan becomes their personal Jesus. And anyone who can stand amid that, see their arms spread wide, hear them chanting "Reach out and touch faith" in unison, and say they're not worried, is lying.

[1] - This wasn't the only piece of officially-sanctioned mischief in promotion of the band at this time. They also tried (successfully) to fix the following year's Brit Awards.

Fan Club Newsletter - c. January 1991. The incriminating evidence of the Fan Club's (successful) attempt to fix the 1990 Brit Awards: a letter urging all fans to take part in a multiple voting scam! Dear Fanclub member This is your chance to help Depeche Mode win an award in the 1990...

dmremix.pro

[2] - Read the article here.

Modus Operandum [The Face, February 1989. Words: John McCready. Pictures: Anton Corbijn / Bart Everly.]

dmremix.pro

dmremix.pro

dmremix.pro