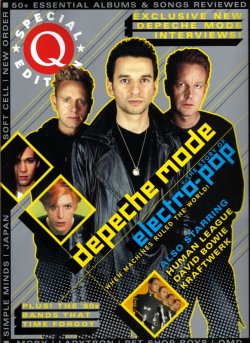

A New Life

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Dave Thompson. Pictures: Joe Bangay / Redferns / Uncredited.]

need pages 50 and continued transcription

They were pissed on from a great height at one of their first gigs. Yet by the end of 1981, synth-wielding Essexmen Depeche Mode had become pop stars. Then it was all over.

The splashing sound wasn’t immediately audible and it blended in so well with the noises coming from the stage that most thought it was part of the show. Then came the first cries of disgust as the audience looked up to see a flood of urine arcing down from the balcony. So it was that in January 1981 Depeche Mode, the band on stage, discovered the true nature of the music industry. They were being pissed on from a great height.

Later, it turned out, it wasn’t really urine. The Cabaret Futura, in London’s Soho, played host to the wildest fringes of the art scene, and the Event Group – guerrilla performance artists with an eye for hysterical outrage – was among the wildest of them all. This night, as Cabaret Futura proprietor Richard Strange recalls, was the night they chose to do “something unspeakable with hoses and fake urine, while the band played underneath.”

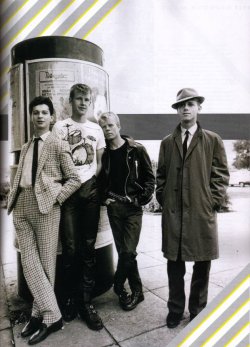

Strange still owns the tapes he made at the Cabaret, and his recording of Depeche Mode remains one of his favourites to this day; a reminder of a time when the band – Martin Gore, David Gahan, Andy Fletcher and Vince Clarke – were “all cherubic-faced and full of nervy swagger”. The band, Strange concludes, “glisten”. [1]

Back then, Depeche Mode had been a band for less than a year. Yet they’d already secured residencies at the Top Alex in Southend and the Bridgehouse, Canning Town, East London, while a song from their first demo tape, Photographic, was lined up for inclusion on what would become the defining document of early-’80s English electronica, DJ Stevo’s Some Bizzare album.

Raised in Basildon, Essex, Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher formed their first band, No Romance In China, in 1977, although they had little time for punk, preferring a repertoire of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Clarke, though, was constantly wondering how to broaden the group’s largely acoustic sound: a question answered one night in 1979 when another local band, Norman And The Worms, turned up for a youth club gig with a new addition to their musical arsenal, guitar-playing bank teller Martin Gore’s Moog Prodigy synthesizer.

Synths were in the news back then anyway, as Gary Numan’s Are “Friends” Electric? had put the instrument into the charts that summer. A second single, Cars, compounded its success. Suddenly, you couldn’t turn a light on without shorting out a thousand would-be synthesizer wizards. The Human League, Ultravox, Cabaret Voltaire, Fad Gadget… all had been experimenting on the fringes for some time. Now, though, they were getting noticed. Martin Gore wanted some of this attention, even if, as he later confessed, “I’d had my own synth for about a month before I realised you could change the sound. You know that sound that goes Waaauuugh? I was stuck on that one for ages.”

Soon Clarke had invested in a drum machine, and he and Gore were regularly rehearsing – or at least, studying synth catalogues in readiness for the day when they’d buy another. When Fletcher, too, gravitated to their side, they already had a new band name waiting: Composition Of Sound.

“I don’t think you’d call it a group,” one of the trio’s schoolmates later recalled. “It was more like a hard core of friends who’d get together to dick around with their instruments [Fletcher’s bass, Clarke’s guitar, Gore’s synth and the drum machine] and a loose outer circle that would egg them on. I don’t think Composition Of Sound played more than three gigs, and they were all disasters.”

The gigs, climaxed by a burbling version of Lt Pigeon’s ’70s novelty hit Mouldy Old Dough, imbued the trio with the confidence they needed to persevere, and persuaded them that the band’s basic line-up wasn’t working. Clarke abandoned guitar for his own synth, Fletcher joined him and, in spring 1980, a fourth member arrived: vocalist Dave Gahan. Though Fletcher did later claim, “We weren’t even sure that it was him we wanted… we got Dave on the strength of him singing Bowie’s Heroes at a jam session with some other band. But there were so many other people singing.”

Gahan soon gifted the band with a name he’d seen on a French fashion magazine cover: Dépêche Mode (translation: fast fashion). Given the speed with which the group’s career would soon be moving, it was an apt choice.

Depeche Mode’s first task was to make something of the original songs in their repertoire. The synth, after all, was the ultimate DIY instrument and insured that, as Fletcher noted, “You don’t have to be a great music to… play and get a message out. We certainly didn’t know anything about music.”

However, Clarke did know something about songwriting, turning out what Richard Strange still calls “wonderful three-minute anthems”, including the three numbers that would comprise Depeche Mode’s first demo, recorded towards the end of 1980: an untitled instrumental, another piece that would eventually surface as the theme to TV’s The Other Side Of The Tracks, and Photographic, the number that caught Stevo’s ear as he pursued the dream of launching his own label.

Stevo already had the basics of the label’s opening shot in place: contributions from Blancmange, The The and Soft Cell – unknowns one and all. Depeche Mode were no more or less regarded than any of them, but they really weren’t keen on the compilation idea, especially after Stevo told them what he intended calling it. The Some Bizzare Album? “But we’re not a bizarre band,” protested Clarke.

However, the group were aware that the album might bring them to the attention of somebody more in tune with the music industry than the handful of offers they’d fielded so far from the Nigerian Rastafarian who wanted to dress them up as aliens and play the nightclubs of Lagos, and supermarket magnate (and Southend United FC chairman) Anton Johnson. Their own attempts to attract conventional offers had resulted in failure and rejection.

Day-tripping around the London labels, Gahan and Clarke dropped by Rough Trade. The proffered tape went down well, but in those days of firm label identities nobody saw Depeche Mode as a Rough Trade band. They did, though, suggest the band contact Daniel Miller, whose label, Mute, they were distributing.

Since launching the previous year, with Miller’s own TVOD / Warm Leatherette single (released in the guise of The Normal), Mute had positioned itself at the vanguard of the experimental electronics scene. Germany’s outré DAF, Robert Rental and San Francisco art terrorist Boyd Rice’s disturbingly ugly Non alter-ego were all Mute triumphs. However, Miller had also shown an ear for less confrontational synth music, when he created the Silicon Teens and their grinning synth deconstruction of a string of old pop classics.

Granted an audience with Miller, Depeche Mode realised they could tell what he thought before he even spoke. “He looked at us,” Gahan shuddered, “and said, Yeeuch. We just thought, Bastard.”

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Dave Thompson. Pictures: Joe Bangay / Redferns / Uncredited.]

The first of three instalments of Depeche Mode history in a Q Special Edition, this section covering up to Vince's departure at the end of 1981. While the story will be familiar to most ardent Mode fans, the piece has some interesting anecdotes, and takes a step back from the band to look more than many articles do at the musical climate that influenced them.

" For once, the equipment was on its best behaviour, the audience were intent on enjoying themselves, and Mouldy Old Dough did not receive the loudest cheer of the evening. Even more surprising than that, though, was the sight of Daniel Miller dancing wildly at the side of the stage. "

need pages 50 and continued transcription

They were pissed on from a great height at one of their first gigs. Yet by the end of 1981, synth-wielding Essexmen Depeche Mode had become pop stars. Then it was all over.

The splashing sound wasn’t immediately audible and it blended in so well with the noises coming from the stage that most thought it was part of the show. Then came the first cries of disgust as the audience looked up to see a flood of urine arcing down from the balcony. So it was that in January 1981 Depeche Mode, the band on stage, discovered the true nature of the music industry. They were being pissed on from a great height.

Later, it turned out, it wasn’t really urine. The Cabaret Futura, in London’s Soho, played host to the wildest fringes of the art scene, and the Event Group – guerrilla performance artists with an eye for hysterical outrage – was among the wildest of them all. This night, as Cabaret Futura proprietor Richard Strange recalls, was the night they chose to do “something unspeakable with hoses and fake urine, while the band played underneath.”

Strange still owns the tapes he made at the Cabaret, and his recording of Depeche Mode remains one of his favourites to this day; a reminder of a time when the band – Martin Gore, David Gahan, Andy Fletcher and Vince Clarke – were “all cherubic-faced and full of nervy swagger”. The band, Strange concludes, “glisten”. [1]

Back then, Depeche Mode had been a band for less than a year. Yet they’d already secured residencies at the Top Alex in Southend and the Bridgehouse, Canning Town, East London, while a song from their first demo tape, Photographic, was lined up for inclusion on what would become the defining document of early-’80s English electronica, DJ Stevo’s Some Bizzare album.

Raised in Basildon, Essex, Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher formed their first band, No Romance In China, in 1977, although they had little time for punk, preferring a repertoire of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Clarke, though, was constantly wondering how to broaden the group’s largely acoustic sound: a question answered one night in 1979 when another local band, Norman And The Worms, turned up for a youth club gig with a new addition to their musical arsenal, guitar-playing bank teller Martin Gore’s Moog Prodigy synthesizer.

Synths were in the news back then anyway, as Gary Numan’s Are “Friends” Electric? had put the instrument into the charts that summer. A second single, Cars, compounded its success. Suddenly, you couldn’t turn a light on without shorting out a thousand would-be synthesizer wizards. The Human League, Ultravox, Cabaret Voltaire, Fad Gadget… all had been experimenting on the fringes for some time. Now, though, they were getting noticed. Martin Gore wanted some of this attention, even if, as he later confessed, “I’d had my own synth for about a month before I realised you could change the sound. You know that sound that goes Waaauuugh? I was stuck on that one for ages.”

Soon Clarke had invested in a drum machine, and he and Gore were regularly rehearsing – or at least, studying synth catalogues in readiness for the day when they’d buy another. When Fletcher, too, gravitated to their side, they already had a new band name waiting: Composition Of Sound.

“I don’t think you’d call it a group,” one of the trio’s schoolmates later recalled. “It was more like a hard core of friends who’d get together to dick around with their instruments [Fletcher’s bass, Clarke’s guitar, Gore’s synth and the drum machine] and a loose outer circle that would egg them on. I don’t think Composition Of Sound played more than three gigs, and they were all disasters.”

The gigs, climaxed by a burbling version of Lt Pigeon’s ’70s novelty hit Mouldy Old Dough, imbued the trio with the confidence they needed to persevere, and persuaded them that the band’s basic line-up wasn’t working. Clarke abandoned guitar for his own synth, Fletcher joined him and, in spring 1980, a fourth member arrived: vocalist Dave Gahan. Though Fletcher did later claim, “We weren’t even sure that it was him we wanted… we got Dave on the strength of him singing Bowie’s Heroes at a jam session with some other band. But there were so many other people singing.”

Gahan soon gifted the band with a name he’d seen on a French fashion magazine cover: Dépêche Mode (translation: fast fashion). Given the speed with which the group’s career would soon be moving, it was an apt choice.

Depeche Mode’s first task was to make something of the original songs in their repertoire. The synth, after all, was the ultimate DIY instrument and insured that, as Fletcher noted, “You don’t have to be a great music to… play and get a message out. We certainly didn’t know anything about music.”

However, Clarke did know something about songwriting, turning out what Richard Strange still calls “wonderful three-minute anthems”, including the three numbers that would comprise Depeche Mode’s first demo, recorded towards the end of 1980: an untitled instrumental, another piece that would eventually surface as the theme to TV’s The Other Side Of The Tracks, and Photographic, the number that caught Stevo’s ear as he pursued the dream of launching his own label.

Stevo already had the basics of the label’s opening shot in place: contributions from Blancmange, The The and Soft Cell – unknowns one and all. Depeche Mode were no more or less regarded than any of them, but they really weren’t keen on the compilation idea, especially after Stevo told them what he intended calling it. The Some Bizzare Album? “But we’re not a bizarre band,” protested Clarke.

However, the group were aware that the album might bring them to the attention of somebody more in tune with the music industry than the handful of offers they’d fielded so far from the Nigerian Rastafarian who wanted to dress them up as aliens and play the nightclubs of Lagos, and supermarket magnate (and Southend United FC chairman) Anton Johnson. Their own attempts to attract conventional offers had resulted in failure and rejection.

Day-tripping around the London labels, Gahan and Clarke dropped by Rough Trade. The proffered tape went down well, but in those days of firm label identities nobody saw Depeche Mode as a Rough Trade band. They did, though, suggest the band contact Daniel Miller, whose label, Mute, they were distributing.

Since launching the previous year, with Miller’s own TVOD / Warm Leatherette single (released in the guise of The Normal), Mute had positioned itself at the vanguard of the experimental electronics scene. Germany’s outré DAF, Robert Rental and San Francisco art terrorist Boyd Rice’s disturbingly ugly Non alter-ego were all Mute triumphs. However, Miller had also shown an ear for less confrontational synth music, when he created the Silicon Teens and their grinning synth deconstruction of a string of old pop classics.

Granted an audience with Miller, Depeche Mode realised they could tell what he thought before he even spoke. “He looked at us,” Gahan shuddered, “and said, Yeeuch. We just thought, Bastard.”

Last edited: