- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

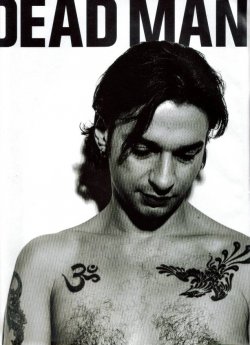

Dead Man Talking

[Arena, April 1997. Words: Gareth Grundy. Pictures: Jake Chessum / Various.]

It’s a rock’n’roll cliché: singer finds stardom and descends into drugs hell. It’s also true. Welcome to the world of Dave Gahan.

"Don’t put too much coke in there, man,” says Dave Gahan to the drug dealer loading his syringe with a blend of cocaine and heroine. “I’m not feeling well.” It’s almost 1am on May 28, 1996, and Gahan, lead singer of Depeche Mode, is sitting in his hotel bathroom at the Sunset Marquis in Los Angeles. Outside, a girl he’s just met in the hotel bar mills about, oblivious to her new friend’s activities.

Back in the bathroom, Gahan injects the cocktail into his arm and looks into the dealer’s eyes. Immediately he knows that something is wrong. Something is very wrong. He passes out ten minutes later and begins to have a heart attack. The dealer tries to revive him. Failing, he drags Gahan into the bedroom where the girl panics, picks up the phone and dials for an ambulance. Terrified of being arrested, the dealer puts the receiver down and refuses to let her make the call. They struggle. She pushes him over and he runs off, only to return minutes later to collect his syringes and some, but not all, of his merchandise.

With the dealer finally gone, the girl makes the call and waits for the paramedics. She throws water and wet towels on Gahan, without effect. She tries to pick him up. Gahan is only slight but he is still too heavy for her to lift. She notices that his hands are turning blue. The colour is beginning to spread up his forearms.

An ambulance arrives at 1.15am and takes Gahan to LA’s Cedars Sinai hospital where his heart stops beating for two minutes before he is revived by doctors. He is then handcuffed to a policeman who accordingly reads him his rights and arrests him for possession of the cocaine found in his hotel room, and for being under the influence of heroin.

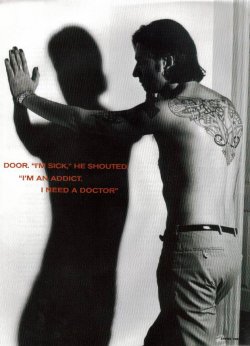

At dawn, Gahan is released from hospital and taken into custody by the LA Sheriff’s department, who lock him in a cell with five other people. Still woozy from the attack and terrified by his new surroundings, Gahan begins banging on his cell door.

“I’m sick,” he shouts. “I’m an addict. I need a doctor.”

A cop gives him a towel and tells him to wipe the sweat off his body. TV crews camp outside the jail and, four hours later, when Gahan is released on $10,000 bail, he’s met by a phalanx of cameras. He uses the opportunity to apologise to his mother.

Dave Gahan was born in Epping on May 9, 1962, but grew up in nearby Basildon. His mother, Sylvia, was in the Salvation Army and sent Gahan to Sunday School every week. He’d play truant and return home lying about what a great time he’d had. His father, Len, left home when he was just six months old. He reappeared when Gahan was five – after his stepfather had died – and stayed for about a year before disappearing again, this time for good.

Gahan was a tearaway as a youngster, notching up juvenile court appearances for stealing cars, vandalism and graffiti. His drug experimentation began as a teenager after thieving some barbiturates which his mother had been prescribed for epilepsy. Soon afterwards he graduated to speed. “A gang of us would go out together and buy a big bag of amphetamines,” he says. “We’d go to a party or club in London and catch the milk train home.” [1]

He left school in 1978 and went through 20 jobs within six months. The following year, he took heroin for the first time, in a King’s Cross squat, but was too enamoured of speed for it to make a lasting impression. Speed was the punk drug and Gahan was in deep, following the Damned and the Clash around the country.

At the turn of the decade, Gahan began frequenting the nascent London club scene. Although he applied to Southend Art College to study display design, he returned more interested in music and auditioned, in 1980, to be the singer for a Basildon synth band called Composition Of Sound. The group’s members – Vince Clarke (who went on to form Yazoo and then Erasure), Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher, all from the polite side of town – had heard Gahan singing Bowie’s “Heroes” at a jam session with another band in the local scout hut. He passed the audition and even came up with a better name, borrowed from the cover of a French fashion magazine: Depeche Mode.

Gahan was 18. Now he’s 34. In the intervening years Depeche Mode (with Alan Wilder, who replaced Clarke after the first album) conquered the world. Their last album, 1993’s Songs Of Faith And Devotion, went to number one in 17 countries. Today, Dave Gahan will tell you that he’s lucky to be alive. He’s not being melodramatic. For the last two and a half years, during which he was addicted to heroin, he didn’t care whether he lived or died. “I was on a death trip,” he says. “For a very long time”.

By late 1990, the pressures of being in Depeche Mode were affecting Dave Gahan’s personal life. Fans were camped outside his house, some even hired private detectives to follow him around. To cap it all, his five-year-old marriage – to Joanne, one-time head of the Mode fan club and mother of his three-year-old son, Jack – was on the rocks.

[Arena, April 1997. Words: Gareth Grundy. Pictures: Jake Chessum / Various.]

An exceptional feature-length piece chronicling, with merciless precision, Dave's fall from grace and rehabilitation. While some articles of this sort milk the salacious details for all they're worth, the writer here has stuck to a relentless, unblinking narrative with very little commentary, not even from Dave himself. The result is harrowing, but just try stopping half way through.

" As he begins posing for photos, Jonathan Kessler enters the room, still in trainers and tracksuit bottoms after his morning run. He asks Gahan if he’s OK.

“Yeah!” he declares, loud enough for everyone to hear.

Then he looks at Kessler, smiles weakly and shakes his head."

It’s a rock’n’roll cliché: singer finds stardom and descends into drugs hell. It’s also true. Welcome to the world of Dave Gahan.

"Don’t put too much coke in there, man,” says Dave Gahan to the drug dealer loading his syringe with a blend of cocaine and heroine. “I’m not feeling well.” It’s almost 1am on May 28, 1996, and Gahan, lead singer of Depeche Mode, is sitting in his hotel bathroom at the Sunset Marquis in Los Angeles. Outside, a girl he’s just met in the hotel bar mills about, oblivious to her new friend’s activities.

Back in the bathroom, Gahan injects the cocktail into his arm and looks into the dealer’s eyes. Immediately he knows that something is wrong. Something is very wrong. He passes out ten minutes later and begins to have a heart attack. The dealer tries to revive him. Failing, he drags Gahan into the bedroom where the girl panics, picks up the phone and dials for an ambulance. Terrified of being arrested, the dealer puts the receiver down and refuses to let her make the call. They struggle. She pushes him over and he runs off, only to return minutes later to collect his syringes and some, but not all, of his merchandise.

With the dealer finally gone, the girl makes the call and waits for the paramedics. She throws water and wet towels on Gahan, without effect. She tries to pick him up. Gahan is only slight but he is still too heavy for her to lift. She notices that his hands are turning blue. The colour is beginning to spread up his forearms.

An ambulance arrives at 1.15am and takes Gahan to LA’s Cedars Sinai hospital where his heart stops beating for two minutes before he is revived by doctors. He is then handcuffed to a policeman who accordingly reads him his rights and arrests him for possession of the cocaine found in his hotel room, and for being under the influence of heroin.

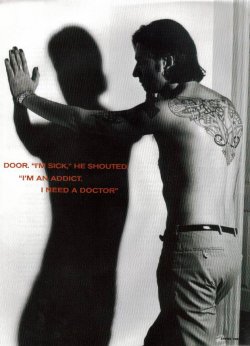

At dawn, Gahan is released from hospital and taken into custody by the LA Sheriff’s department, who lock him in a cell with five other people. Still woozy from the attack and terrified by his new surroundings, Gahan begins banging on his cell door.

“I’m sick,” he shouts. “I’m an addict. I need a doctor.”

A cop gives him a towel and tells him to wipe the sweat off his body. TV crews camp outside the jail and, four hours later, when Gahan is released on $10,000 bail, he’s met by a phalanx of cameras. He uses the opportunity to apologise to his mother.

Dave Gahan was born in Epping on May 9, 1962, but grew up in nearby Basildon. His mother, Sylvia, was in the Salvation Army and sent Gahan to Sunday School every week. He’d play truant and return home lying about what a great time he’d had. His father, Len, left home when he was just six months old. He reappeared when Gahan was five – after his stepfather had died – and stayed for about a year before disappearing again, this time for good.

Gahan was a tearaway as a youngster, notching up juvenile court appearances for stealing cars, vandalism and graffiti. His drug experimentation began as a teenager after thieving some barbiturates which his mother had been prescribed for epilepsy. Soon afterwards he graduated to speed. “A gang of us would go out together and buy a big bag of amphetamines,” he says. “We’d go to a party or club in London and catch the milk train home.” [1]

He left school in 1978 and went through 20 jobs within six months. The following year, he took heroin for the first time, in a King’s Cross squat, but was too enamoured of speed for it to make a lasting impression. Speed was the punk drug and Gahan was in deep, following the Damned and the Clash around the country.

At the turn of the decade, Gahan began frequenting the nascent London club scene. Although he applied to Southend Art College to study display design, he returned more interested in music and auditioned, in 1980, to be the singer for a Basildon synth band called Composition Of Sound. The group’s members – Vince Clarke (who went on to form Yazoo and then Erasure), Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher, all from the polite side of town – had heard Gahan singing Bowie’s “Heroes” at a jam session with another band in the local scout hut. He passed the audition and even came up with a better name, borrowed from the cover of a French fashion magazine: Depeche Mode.

Gahan was 18. Now he’s 34. In the intervening years Depeche Mode (with Alan Wilder, who replaced Clarke after the first album) conquered the world. Their last album, 1993’s Songs Of Faith And Devotion, went to number one in 17 countries. Today, Dave Gahan will tell you that he’s lucky to be alive. He’s not being melodramatic. For the last two and a half years, during which he was addicted to heroin, he didn’t care whether he lived or died. “I was on a death trip,” he says. “For a very long time”.

By late 1990, the pressures of being in Depeche Mode were affecting Dave Gahan’s personal life. Fans were camped outside his house, some even hired private detectives to follow him around. To cap it all, his five-year-old marriage – to Joanne, one-time head of the Mode fan club and mother of his three-year-old son, Jack – was on the rocks.

[1] - This is the one complaint I have with the article - from how the writer jumps from his mid-1990s drug problems to his early experimenting, and then (as you'll see) misses out the 1980s entirely, you'd be forgiven for thinking that Dave was some hardcore drug fiend all his years. He wasn't - for a large chunk of the 1980s he not only stayed away from the drugs (of any description), but was somewhat prudish in tone, regarding Martin's heavy partying as something he'd long grown out of. It was in 1987 when he started to head downhill again, doing cocaine on the Music For The Masses tour.