Deconstruction Time Again

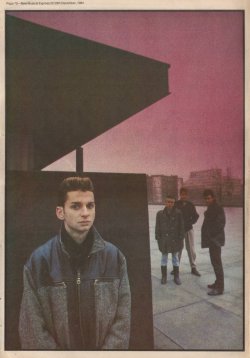

[NME, 22nd December 1984. Words: Don Watson. Pictures: Derek Ridgers.]

You thought they were prissy pinkos. But no! They drink, talk to girls, wear leather mini-skirts! Don Watson walks tall with Depeche Mode, the new Neubatens of Basildon. Photos by Derek Ridgers.

It’s just one of those winter evenings.

Depeche Mode’s “Some Great Reward” LP plays inside the room while outside the window, and behind the opposite terrace, the tower block windows light up one by one.

The telephone rings.

Cracking down the line, a strained voice echoes the sound inside the record machine: “I can’t stand another drink / It’s surprising this town doesn’t sink… Is there something to do?”

Probably not, but then there’s another temporary reprieve in the offing – a few wild nights in Berlin, the chance to chat with the nice boys from Depeche Mode.

“Depeche Mode,” crackles the voice in the phone, “who exactly are they anyway?”

Good point. Given half an hour I could name you all their singles; given half a bottle I could sing you a few as well, with a medley from the LPs as an encore. But describe a member of Depeche Mode? Well, one of them’s got a blonde fringe, but then so have I, one of them looks like an old friend of mine who looked sort of… normal. And the other two? Pass. [1]

Flicking through the NME archives for further information, with the rationale that to recognise your interviewee might not be a bad idea, something begins to emerge.

“Are you a member of Depeche Mode?” a young Basildon boy asked Paul Morley in 1981. [2]

“What happened to your fringe?” a Dublin girl asked X. Moore in 1983 (tantamount to asking Ian Paisley what happened to that nifty black beret and shades combo he used to wear to terrorist funerals). [3]

By the time I arrive at the Munich hotel, to be greeted by clutches of wide-eyed and hopeful-looking Bavarian boppers proffering pens and paper and demanding autographs, I’m beginning to twig something – NOBODY knows who Depeche Mode are.

I consider really confusing them by signing anyway, but hell, why should I do the band’s PR work? I’m not him – eiben spien ein journalist! They clearly don’t believe me.

Later I discover a genuine Mode, Andrew Fletcher – Fletch, natch! – bright-eyed, ginger-haired and blessed with possession of a pair of black NHS glasses that never rest on face or in case for too long at a time.

“We actually base our style on the NME journalists,” he explains, “in fact we were hoping to discuss a deal whereby you, X. Moore, Paul Morley and another of your choice go on the road for us, while we have a month off.”

On the road? Shiver. Well, I’m not sure you could afford the other two, and I could foresee some disagreements on band direction.

“You big in Germany then?” enquires straight man photographer Derek Ridgers, who does not, during the entire stay, get mistaken for a member of Depeche Mode.

“About six foot two,” replies Fletch gleefully.

In fact, Depeche Mode are moderately enormous in Germany. In Munich they play to a hall packed with hip and hysterical young things (and plain things), a capacity crowd of great haircuts, lousy dancers and lighter flames held aloft. In Berlin they play to a capacity crows and a selection of fireworks in a cycle track.

Fletch pauses for thought. “Are we a mega-band?” he wonders.

Depeche Mode could sell-out the world, and still be one of the least mega-bands on the planet. They may play football stadiums, but their sound will still be stamped indelibly with the mark of the youth club disco – which is, in itself neither a good or bad thing, just a fact. Depeche are the original small town boys. The question is, given that, what do they do: and the answer is quite a lot.

The stated aim of pop music in 1984 appears to be regression, its position strictly foetal. Meanwhile the music press for the most part adopts an attitude of cowed condescension: “Yes that’s all very well, but if I was a mentally retarded six-year-old, I’d want Boy George telling me that war is stupid too.”

In the Face of this, Depeche Mode are a Sound that in its own small way remains committed to the idea of pop music as a dynamic force – eclectic and even plagiaristic but always open. The difference between “People are people” and “War is stupid” as a statement may be minimal, but if you want a statement phone the bank; the difference between George’s Moonie chant and Depeche Mode’s shiny metal pop is where my interest lies.

The show in Munich is punchy, polished but still unpredictable enough to rupture the melodic surface. Dave Gahan, once the most unassuming of front men, races around the stage jerking hips and engaging the audience in call and response routines. If this were Bono I might throw up, yet in this context these gestures appear just what they are – a bizarre and rather amusing ritual.

“Full of 14 and 15-year-olds,” bemoans one backstage sweetie who might just have scraped 16.

How do you feel now you’ve sold out, Fletch?

“Sick as a parrot.”

Right.

At this point hordes of girls burst into the dressing rooms. “Depeche Mode, After Show” read the passes; scrawled below in thick black felt tip they all read “Sex”.

Dave Gahan groans, conversation is interrupted.

Depeche Mode have become a big noise, but they’ll never be faces. In an age of stultifying conformity – of the well-rounded sound, the docile look and the manufactured style – they are a charming anachronism. They have a personal anatomy that bears no relation to the reluctant facelessness of Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw, because it is not a front for mediocrity. They are not non-entities struggling to be somebodies, they simply are – gawky, inelegant, likeable, sharp.

They’ll never record a masterpiece with the quivering angst of an “Art Of Falling Apart”, but in their own clean way they continue to produce pop singles with a shiver of… well, if not the forbidden, at least the unexpected: “See You” with its echoed tones and buried vocals, “Everything Counts” with its offbeat sweetness and verbal slapstick, “Blasphemous Rumours” with its arch naivety and hidden percussive edge.

By the next day the fans who inhabit the lobby of the hotel seem to have worked out that I’m not part of the band.

The first thing I am faced with, in fact, is a TV camera (not before breakfast, please). The people behind the lens may not take me for a Mode, but they may have any number of unsavoury roles in their slice of fiction to slot me into – dealer, male groupie or leather skirt maker. For this is Bravo TV, an offshoot of Germany’s apocryphal pop mag.

“It’s no good refusing to talk to them,” says Fletch, “they’ll just go ahead and make it up anyway.

“The last time we refused an interview with them, they made up a story about Dave having to be carried off-stage at the end of every performance, taken to a separate dressing room and kept supplied with constant fluids.

“The time before that they said we hated everyone under 20, which made us very popular with their readership.”

As we make our way through the swing doors, Dave makes a theatrical fall on the hotel courtyard.

“Help! I need a cup of coffee,” he wails as the rest of the band crowd around him.

“Oh God!” shams Al, “this happens all the time.”

The camera moves in closer.

[NME, 22nd December 1984. Words: Don Watson. Pictures: Derek Ridgers.]

A lively and absorbing long article / discussion looking at Depeche Mode in the year which, more than any other, they broke out of their mould. The author actually sounds genuine when he pokes holes in the old "red rockers" stereotype just as easily as the even older one of "wimps with synths". This gives them a fair hearing as far as influences are concerned, as well as providing some amusing anecdotes about their continental following.

" Depeche Mode have become a big noise, but they’ll never be faces. In an age of stultifying conformity – of the well-rounded sound, the docile look and the manufactured style – they are a charming anachronism. They have a personal anatomy that bears no relation to the reluctant facelessness of Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw, because it is not a front for mediocrity. They are not non-entities struggling to be somebodies, they simply are – gawky, inelegant, likeable, sharp. "

You thought they were prissy pinkos. But no! They drink, talk to girls, wear leather mini-skirts! Don Watson walks tall with Depeche Mode, the new Neubatens of Basildon. Photos by Derek Ridgers.

It’s just one of those winter evenings.

Depeche Mode’s “Some Great Reward” LP plays inside the room while outside the window, and behind the opposite terrace, the tower block windows light up one by one.

The telephone rings.

Cracking down the line, a strained voice echoes the sound inside the record machine: “I can’t stand another drink / It’s surprising this town doesn’t sink… Is there something to do?”

Probably not, but then there’s another temporary reprieve in the offing – a few wild nights in Berlin, the chance to chat with the nice boys from Depeche Mode.

“Depeche Mode,” crackles the voice in the phone, “who exactly are they anyway?”

Good point. Given half an hour I could name you all their singles; given half a bottle I could sing you a few as well, with a medley from the LPs as an encore. But describe a member of Depeche Mode? Well, one of them’s got a blonde fringe, but then so have I, one of them looks like an old friend of mine who looked sort of… normal. And the other two? Pass. [1]

Flicking through the NME archives for further information, with the rationale that to recognise your interviewee might not be a bad idea, something begins to emerge.

“Are you a member of Depeche Mode?” a young Basildon boy asked Paul Morley in 1981. [2]

“What happened to your fringe?” a Dublin girl asked X. Moore in 1983 (tantamount to asking Ian Paisley what happened to that nifty black beret and shades combo he used to wear to terrorist funerals). [3]

By the time I arrive at the Munich hotel, to be greeted by clutches of wide-eyed and hopeful-looking Bavarian boppers proffering pens and paper and demanding autographs, I’m beginning to twig something – NOBODY knows who Depeche Mode are.

I consider really confusing them by signing anyway, but hell, why should I do the band’s PR work? I’m not him – eiben spien ein journalist! They clearly don’t believe me.

Later I discover a genuine Mode, Andrew Fletcher – Fletch, natch! – bright-eyed, ginger-haired and blessed with possession of a pair of black NHS glasses that never rest on face or in case for too long at a time.

“We actually base our style on the NME journalists,” he explains, “in fact we were hoping to discuss a deal whereby you, X. Moore, Paul Morley and another of your choice go on the road for us, while we have a month off.”

On the road? Shiver. Well, I’m not sure you could afford the other two, and I could foresee some disagreements on band direction.

“You big in Germany then?” enquires straight man photographer Derek Ridgers, who does not, during the entire stay, get mistaken for a member of Depeche Mode.

“About six foot two,” replies Fletch gleefully.

In fact, Depeche Mode are moderately enormous in Germany. In Munich they play to a hall packed with hip and hysterical young things (and plain things), a capacity crowd of great haircuts, lousy dancers and lighter flames held aloft. In Berlin they play to a capacity crows and a selection of fireworks in a cycle track.

Fletch pauses for thought. “Are we a mega-band?” he wonders.

Depeche Mode could sell-out the world, and still be one of the least mega-bands on the planet. They may play football stadiums, but their sound will still be stamped indelibly with the mark of the youth club disco – which is, in itself neither a good or bad thing, just a fact. Depeche are the original small town boys. The question is, given that, what do they do: and the answer is quite a lot.

The stated aim of pop music in 1984 appears to be regression, its position strictly foetal. Meanwhile the music press for the most part adopts an attitude of cowed condescension: “Yes that’s all very well, but if I was a mentally retarded six-year-old, I’d want Boy George telling me that war is stupid too.”

In the Face of this, Depeche Mode are a Sound that in its own small way remains committed to the idea of pop music as a dynamic force – eclectic and even plagiaristic but always open. The difference between “People are people” and “War is stupid” as a statement may be minimal, but if you want a statement phone the bank; the difference between George’s Moonie chant and Depeche Mode’s shiny metal pop is where my interest lies.

The show in Munich is punchy, polished but still unpredictable enough to rupture the melodic surface. Dave Gahan, once the most unassuming of front men, races around the stage jerking hips and engaging the audience in call and response routines. If this were Bono I might throw up, yet in this context these gestures appear just what they are – a bizarre and rather amusing ritual.

“Full of 14 and 15-year-olds,” bemoans one backstage sweetie who might just have scraped 16.

How do you feel now you’ve sold out, Fletch?

“Sick as a parrot.”

Right.

At this point hordes of girls burst into the dressing rooms. “Depeche Mode, After Show” read the passes; scrawled below in thick black felt tip they all read “Sex”.

Dave Gahan groans, conversation is interrupted.

Depeche Mode have become a big noise, but they’ll never be faces. In an age of stultifying conformity – of the well-rounded sound, the docile look and the manufactured style – they are a charming anachronism. They have a personal anatomy that bears no relation to the reluctant facelessness of Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw, because it is not a front for mediocrity. They are not non-entities struggling to be somebodies, they simply are – gawky, inelegant, likeable, sharp.

They’ll never record a masterpiece with the quivering angst of an “Art Of Falling Apart”, but in their own clean way they continue to produce pop singles with a shiver of… well, if not the forbidden, at least the unexpected: “See You” with its echoed tones and buried vocals, “Everything Counts” with its offbeat sweetness and verbal slapstick, “Blasphemous Rumours” with its arch naivety and hidden percussive edge.

By the next day the fans who inhabit the lobby of the hotel seem to have worked out that I’m not part of the band.

The first thing I am faced with, in fact, is a TV camera (not before breakfast, please). The people behind the lens may not take me for a Mode, but they may have any number of unsavoury roles in their slice of fiction to slot me into – dealer, male groupie or leather skirt maker. For this is Bravo TV, an offshoot of Germany’s apocryphal pop mag.

“It’s no good refusing to talk to them,” says Fletch, “they’ll just go ahead and make it up anyway.

“The last time we refused an interview with them, they made up a story about Dave having to be carried off-stage at the end of every performance, taken to a separate dressing room and kept supplied with constant fluids.

“The time before that they said we hated everyone under 20, which made us very popular with their readership.”

As we make our way through the swing doors, Dave makes a theatrical fall on the hotel courtyard.

“Help! I need a cup of coffee,” he wails as the rest of the band crowd around him.

“Oh God!” shams Al, “this happens all the time.”

The camera moves in closer.

[1] - You might have thought that another seventeen years in the limelight would change all that. But no. Huge swathes of this 2001 article are given over to pondering the band members' virtual anonymity.

[2] - That's here.

[3] - And although it's not actually in it, that'll be in connection with this article.

Last edited: