- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

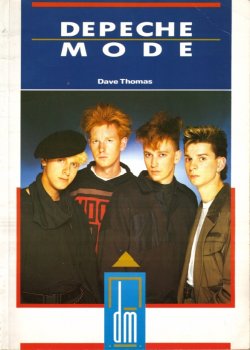

Depeche Mode

[Bobcat Books, London 1986. Words: Dave Thomas. Cover picture: London Features International Ltd / Barry Plummer]

Few instruments can claim to have made a greater impact on popular music than the synthesizer. The electric guitar, of course, outranks the synth in historical terms and arguably, rock'n'roll music might never have existed, but for the tireless inventiveness of Leo Fender and Les Paul. Then there are the many and various developments in recording techniques, the absence of any one of which could have changed the entire course of popular music. But it was the synth which truly revolutionised rock and, more than any other instrument, propelled the beast headlong into the 1980s.

The synthesizer, in its simplest form, is an electronic device which can create and shape sound patterns. It was first developed in the late 1920s, but it wasn't until the mid-sixties that its possibilities as a musical instrument were truly explored - by Dr. Robert Moog, an American electronics engineer after whom one of the world's most popular synthesizers is named. He attached a keyboard to a synthesizer for the first time, and by 1071 the Mini-Moog, a portable instrument which swiftly found favour among leading rock bands of the day, was on sale. Less than fifteen years before, Columbia Studios had been forced to clear out an entire room in order to install a similar device.

Roxy Music, Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream, The Who and Hawkwind were all among the early pioneers of the instrument. In 1974, Kraftwerk enjoyed a massive hit on both sides of the Atlantic with 'Autobahn', a record which was almost exclusively electronic, and three years later David Bowie and Brian Eno were to employ the instrument to quite devastating effect on Bowie's 'Low' and 'Heroes' albums. Simultaneously, Ultravox, Japan and Rikki & The Last Days Of Earth introduced the synthesizers to the Punk/New Wave and by the end of the decade these two points had come together in the flower of a whole new generation of young musicians.

As the 1970s progressed, so the price of synths dropped. After opening the decade as little more than a rich man's plaything, a decent synth could now be purchased for little more than a the cost of a good guitar. It was also easier to play, another attraction for the budding musician who was unwilling to spend a fortune in time and sticking plasters trying to master a fretted instrument. And finally, with a synth, the most extraordinary sounds were available at the touch of a button.

It was this which first attracted Daniel Miller to the instrument. As guitarist in a school band he constantly outraged fellow musicians by playing guitar not with fingers and chords, but by hitting it with bits of metal, experimenting with sound. At art school in Guildford has talent might have lain in film making - one effort, a 20 minute comedy called 'Don't Sit Too Close' won a National Film Festival award - but his mind was on blending electronics with popular music. And as a DJ in Switzerland in 1976, he might have outwardly enjoyed playing Abba and Boney M to the tourists, but inside he was seething, impatiently watching the development of Punk music in England and plotting the day when the synth, with its unlimited scope for the untrained musician, would be accepted as the logical punk instrument. "A synth meant you didn't even need to know how to hold a guitar in order to express yourself," he said.

By 1979 Daniel Miller had proved his point. 'TVOD', the first release on his Mute label, had sold over 40,000 copies - not enough to make Daniel, who as The Normal was responsible for the record, a rich man, but more than enough to encourage him in his dream of providing a regular outlet for other non-musicians who, like himself, used pure electronics to generate sound. Artists such as Fad Gadget and Boyd Rice kept release schedules ticking and within 18 months of starting out, Mute Records was firmly established as the prodigal of the independent British music scene.

[Bobcat Books, London 1986. Words: Dave Thomas. Cover picture: London Features International Ltd / Barry Plummer]

Short paperback biography of the band. The author spends a disproportionate amount of time covering the very early years and begins with a detailed examination of the music scene which led to Depeche Mode's appearance. The time after 1981 seems to be written more as a chore, covering little more than the names and dates of releases. Consequently this book is useful as a very basic overview only of their early career. On the other hand, if you are interested in their absolute beginnings or the music world generally in the late seventies, there is plenty to immerse yourself in here.

Few instruments can claim to have made a greater impact on popular music than the synthesizer. The electric guitar, of course, outranks the synth in historical terms and arguably, rock'n'roll music might never have existed, but for the tireless inventiveness of Leo Fender and Les Paul. Then there are the many and various developments in recording techniques, the absence of any one of which could have changed the entire course of popular music. But it was the synth which truly revolutionised rock and, more than any other instrument, propelled the beast headlong into the 1980s.

The synthesizer, in its simplest form, is an electronic device which can create and shape sound patterns. It was first developed in the late 1920s, but it wasn't until the mid-sixties that its possibilities as a musical instrument were truly explored - by Dr. Robert Moog, an American electronics engineer after whom one of the world's most popular synthesizers is named. He attached a keyboard to a synthesizer for the first time, and by 1071 the Mini-Moog, a portable instrument which swiftly found favour among leading rock bands of the day, was on sale. Less than fifteen years before, Columbia Studios had been forced to clear out an entire room in order to install a similar device.

Roxy Music, Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream, The Who and Hawkwind were all among the early pioneers of the instrument. In 1974, Kraftwerk enjoyed a massive hit on both sides of the Atlantic with 'Autobahn', a record which was almost exclusively electronic, and three years later David Bowie and Brian Eno were to employ the instrument to quite devastating effect on Bowie's 'Low' and 'Heroes' albums. Simultaneously, Ultravox, Japan and Rikki & The Last Days Of Earth introduced the synthesizers to the Punk/New Wave and by the end of the decade these two points had come together in the flower of a whole new generation of young musicians.

As the 1970s progressed, so the price of synths dropped. After opening the decade as little more than a rich man's plaything, a decent synth could now be purchased for little more than a the cost of a good guitar. It was also easier to play, another attraction for the budding musician who was unwilling to spend a fortune in time and sticking plasters trying to master a fretted instrument. And finally, with a synth, the most extraordinary sounds were available at the touch of a button.

It was this which first attracted Daniel Miller to the instrument. As guitarist in a school band he constantly outraged fellow musicians by playing guitar not with fingers and chords, but by hitting it with bits of metal, experimenting with sound. At art school in Guildford has talent might have lain in film making - one effort, a 20 minute comedy called 'Don't Sit Too Close' won a National Film Festival award - but his mind was on blending electronics with popular music. And as a DJ in Switzerland in 1976, he might have outwardly enjoyed playing Abba and Boney M to the tourists, but inside he was seething, impatiently watching the development of Punk music in England and plotting the day when the synth, with its unlimited scope for the untrained musician, would be accepted as the logical punk instrument. "A synth meant you didn't even need to know how to hold a guitar in order to express yourself," he said.

By 1979 Daniel Miller had proved his point. 'TVOD', the first release on his Mute label, had sold over 40,000 copies - not enough to make Daniel, who as The Normal was responsible for the record, a rich man, but more than enough to encourage him in his dream of providing a regular outlet for other non-musicians who, like himself, used pure electronics to generate sound. Artists such as Fad Gadget and Boyd Rice kept release schedules ticking and within 18 months of starting out, Mute Records was firmly established as the prodigal of the independent British music scene.