1. “Stop that bloody clacking! I’m trying to watch the telly! Why can’t you find normal hobbies?”

Vince Clarke’s mum would regularly interrupt early Depeche Mode rehearsals to complain about the noise.

Back in the summer of 1980, Depeche Mode were about as far from Pasadena Rose Bowl glory as it is possible to be. Rehearsing in Vince’s drafty garage, their ambitions extended no further than hustling a gig at a newly-opened club called Crocs in Rayleigh, so called because a live crocodile inhabited a pool in the middle of the dance-floor.

The three founder members all lived in Basildon, a plain and characterless Essex town with a population of 180,000.

Vince Clarke (born 3.7.60) had formed one half of a gospel duo. He also played, apparently without enthusiasm, in another band called No Romance In China, who were once described by one witness as “an unlikely cross between The Monkees and Uriah Heep with a little George Formby thrown in for good measure!”

Andy “Fletch” Fletcher (8.7.60) attended Boys’ Brigade meetings with Vince. [1] He was an obsessive Deep Purple fan. His burning ambition as an adolescent was to possess one of Ritchie Blackmore’s plectrums. Martin “Curly-Top” Gore had attended the same school as Fletch. His schooldays were distinguished only by his prowess on the cricket field. A regular member of the school cricket team, his spin-bowling was apparently the toast of South Basildon. Gore’s musical obsessions included Roxy Music, The Rubettes and Sparks. He had played guitar for two local bands, The French Look and Norman & The Worms, the latter of which performed a new wave version of “Skippy The Bush Kangaroo”.

Clarke, Fletcher and Gore decided to form a band the day Johnny Logan’s “What’s Another Year” made it to number one in the charts, in May 1980. Vince played guitar, sang and operated the drum machine, Fletch played bass guitar, Gore played lead guitar.

Initially, they were undecided as to their direction. Their shilly-shallying was perhaps typical of new bands starting out in the first months of the Eighties, a time of endless musical cul-de-sacs. By the end of the Seventies, punk’s hectic charge had violently diffused. The post-punk hinterland was littered with reckless experimentalists, skinny-tie new-wavers, dim traditionalists, waggish absurdists, hopeful stylemongers, earnest politicists…

1980 was the year of Curtis’ death, Lennon’s assassination, massive youth unemployment, riots in Switzerland, CND and music biz recession. It was the year of Talking Heads’ “Remain In Light”, Dexy’s “Young Soul Rebels” and Echo And The Bunnymen’s “Crocodiles”. It was also the year of Oi, Spandau, Ze, Postcard, Factory, Adam, new rockabilly and new HM. A confusing, bewildering 12 months of crazed transition.

Most importantly for three unworldly Basildon striplings it was the year when electronic went pop in a big way.

Before Vince, Fletch and Gore discovered the synthesiser, they first had to choose a name. Early possibilities were The Lemon Peels, Changes, Airport Coffee, Peter Bonetti’s Boots (they were all Chelsea FC fans), The Runny Smiles and The Glow Worms. Eventually, after much prolonged debate they settled on Vince’s favourite, Composition Of Sound. Under this name, they played their first gig as a three-piece, at Scamps in Southend.

By the time they were doing the rounds of local parties, both Vince and Gore had traded in their guitars for synthesisers. Through the summer of 1980, the Depeche Mode sound was forged. When Vince received a call from an old school-friend enquiring about the progress of the band, Vince would proudly announce, “We’ve just gone electronic”.

By the start of 1980, synthesiser bands were beginning to edge into the mainstream. In a sense, the advent of the synth was an inevitable development of the post-punk years. It was cheap, convenient and (best of all) relatively easy to learn to play. The ultimate DIY instrument.

Synthesisers had been commercially available since 1964, but had made little impression on rock and pop until The Beatles added some very discreet synthesiser sounds to their 1969 album, “Abbey Road”. The early Seventies witnessed the first truly innovative use of the synthesiser in rock, most notably in the music of Suicide, Can and Kraftwerk. We’ll leave Vangelis, ELP, Pink Floyd, Tangerine Dream and Jean-Michel Jarre out of this. Ditto Hot Butter (“Popcorn”) and Chicory Tip (“Son Of My Father”).

It might be argued that electro-pop as we know it was born in May 1975, when Kraftwerk scored a hit with “Autobahn”. Their revolutionary use of synths, electronic percussion, sequencers and tape looks would prove to have an enormous influence on the music of the late Seventies and Eighties. While Bowie and Moroder openly admitted their debt, Kraftwerk’s hypnotic pulsebeat was used as a blueprint for electro, hip hop and House.

Firstly though, Suicide and Kraftwerk were to act as catalysts for many of the bands that emerged in the immediate post-punk melee. When Kraftwerk’s Ralf Hutter said in 1977, “Already the guitar is a relic of the Middle Ages and the synth is the instrument of the future,” he must have touched a crucial nerve in many bedrooms and garages.

As early as 1978, synth / electronic groups were making a considerable impression. Cabaret Voltaire, Dalek I (Love You), Deutsche Amerikanische Freundschaft (DAF), Ultravox, Yellow Magic Orchestra and (even) Tubeway Army might have been hastily shunned by punk purists but, together, they were rationalising the possibilities of electronic pop.

The following two years would see the emergence of Human League, Japan, Fad Gadget, OMD, Soft Cell and Blancmange. None of this could have escaped the notice of the three members of Composition Of Sound back in Basildon.

“We’re learning fast,” Martin Gore would say later. “We really started paying attention to what was happening out there. Out in Basildon, all we could do was watch, wait and learn. To us, the synth was a punk instrument. It was an instant DIY tool. Because it was still fairly new, its potential seemed limitless. It gave us a chance to explore.”

Composition Of Sound began gigging regularly, quickly achieving their ambition of headlining at Rayleigh’s Crocs on its special Saturday night electronic showcase. Here they were spotted by a Some Bizzare supreme, Stevo, then a guiding light on the emergent Futurist scene. Only his fiercest exhortations could persuade them to contribute a track to the compilation of new and unsigned talent he was then putting together, eventually to appear as the “Some Bizzare” album in February 1981.

With Vince Clarke growing increasingly uneasy in his role as frontman it was decided to recruit a vocalist. The band were ignorant of the time-honoured small ad in Melody Maker process, so they decided to wait until the right man came along. [2] While waiting to rehearse in a local scout-hut, they heard Dave Gahan crooning “Heroes” with another band. Andy Fletcher would later claim that they invited Gahan to join them there and then, Gahan himself would insist, “They only asked me to join because Vince thought I looked so pretty in my Marks & Spencer jumper and my corduroy trousers. Bastard!”

Gahan was born in Epping on May 9, 1962, and had lived in Basildon since early childhood. He passed through a largely ill-spent youth, earning himself three appearances in juvenile court, “for nicking cars and motorbikes, setting cars alight, spraying walls, vandalism and loads of other wrongful doings!” After leaving school, he passed through 20 jobs in six months, including sweeping the floors in a local supermarket, labouring on a building site and office-clerk for North Sea Gas. When he joined the group, he was studying window design at Southend Technical College. His favourite groups at the time were The Lurkers, The Damned and Sham 69.

Shortly after joining, Gahan suggested a change of name. One afternoon in the rehearsal room, he was browsing through a French fashion magazine when he saw a headline that read, Depeche Mode, roughly translated as, “hurried fashion”.

[1] - No, Andy was born in 1961. In 1986, a not-particularly-inspired biography of Depeche Mode was published.

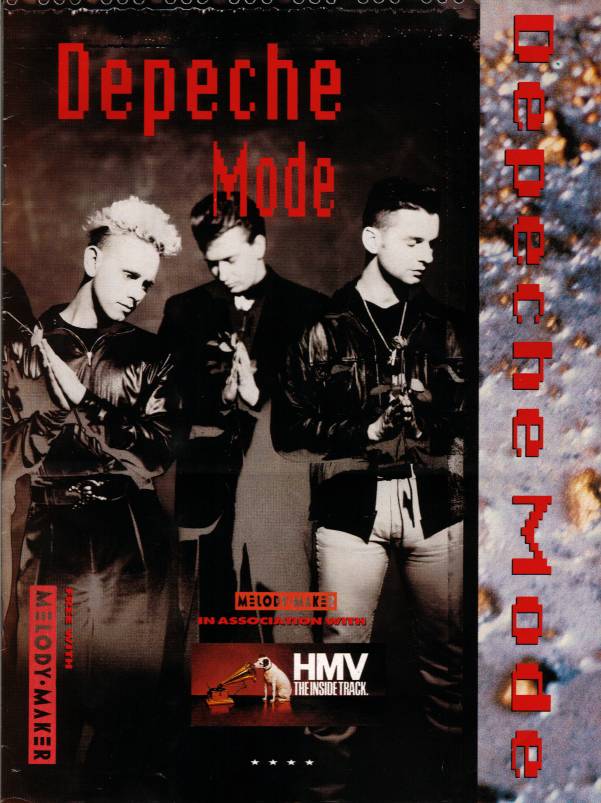

Depeche Mode [Bobcat Books, London 1986. Words: Dave Thomas. Cover picture: London Features International Ltd / Barry Plummer] Short paperback biography of the band. The author spends a disproportionate amount of time covering the very early years and begins with a detailed examination of the...

dmremix.pro

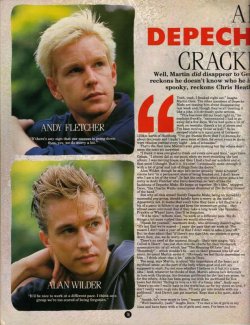

For almost a decade this was the only book available on the band, and some journalists relied on it rather more than they ought to, especially for magazine-format mini "biographies" that did little more than rehash the 1986 book with little or no other research (here's a fine example from 1987).

Depeche Mode Magazine - Living In The Machine Age [Circuit Communications, 1987. Words: Mike Martin. Pictures: All Action Photographic / Pictorial Press / Rex Features.] " For the past 7 years, Depeche Mode have continued to conjure up a potent blend of contagious melodies, irresistible rhythms...

dmremix.pro

The present item is another in this mercifully short series: I can tell straight away which authors have used the 1986 book as their main reference by whether or not they get Andy's year of birth correct.

[2] - It wasn't so much ignorance as the sensible conviction that a stranger drafted in from out of the area wouldn't gel as well with the three existing band members, whatever their capabilities.