- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

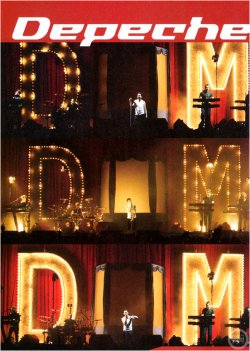

Depeche Mode / Producer Mark Bell: Studio Excitement

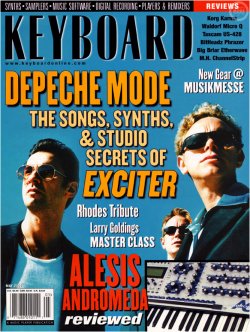

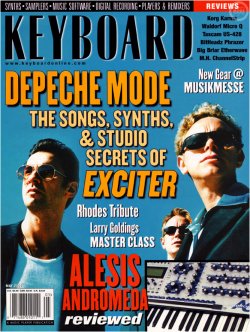

[Keyboard, May 2001, Words: Robert L. Doerschuk. Pictures: Anton Corbijn.]

Back in 1980, when the prototype version of Depeche Mode took form in Basildon, England, eagle-eyed British journalists looked them over and decided they fit into the trendy New Romantic sub-genre, though some punk residue cast a shadow or two over their look and sound. What made them different was their commitment to dragging synthesizers away from the sterile dance-oriented pop of Kraftwerk into a more song-driven, mainstream context.

That was a lifetime ago. In the intervening decades they've released 14 albums, the most recent, 'Ultra', in 1997. That's a substantial body of creative work, and the band can boast more than a few chart-surfing hits. Yet, aside from the sheer endurance, what may impress fans most about these guys is the fact that through the long parade of trends in pop music, they've kept their sound intact and vital.

Need proof? Flash back to 1983, after co-founder Vince Clarke packed up his peppy sequences and split to form Yaz. The band is riding high with 'Everything Counts'. Now kidnap some unsuspecting fans from the local vinyl shop, zoom them to the present, and play them parts of 'Exciter', the milky drones and slithery, slow-mo synth lines of 'Shine', or the Munster-like, lead-footed plod from 'Dead of Night'. Whatever track you pick, your victims will flash a knowing look and say, "So, you got the new Depeche Mode."

Rather than get lost in a struggle to reinvent themselves, this band - like Louis Armstrong, the Stones, and Philip Glass - has made it their mission to keep doing what they do best, and to do it better than ever. 'Exciter', with its unsettling chord changes, darkly glistening timbres, inexpressive yet somehow affecting vocals, and allergy to punchy backbeats, argues that they've succeeded once again.

You say they're stagnating? Standing still? Not for a minute. They're being true to their vision. In spirit, Depeche Mode is an artifact dating back to a time when electronic pop was new, when the artists who explored it were drawn more by its potential than by any instinct to conform. They've influenced many, particularly in ambient circles, yet no one has put all the pieces together - the craft of their songs, the experimental spirit of their arrangements - with as much consistency and originality as Depeche Mode themselves.

We explored these issues one afternoon in March with two thirds of Depeche Mode, Andrew Fletcher and Martin Gore. A few days later, 'Exciter' producer Mark Bell agreed to answer email questions about his involvement and perspective on the project; his thoughts appear on page 38.

Does 'Exciter' have any particular identity for you, as you consider it in the context of your catalog?

Gore: This record is far too close at the moment. We've been working on it for the last year and a half. I still find it really hard to judge any of our records. We just work on them far too much, and play them far too much. We're the last persons you should ask, with the least perspective.

Fletcher: For us, we remember distinct periods of our career that stick out. But we don't really conceptualize too much. We do things very naturally. When we started out, the electronic purists said there were rules we had to stick to. We didn't really use guitars, even though the guitar was my first instrument; I started playing it when I was 13. I hadn't even attempted keyboards until I was at least 16 or 17. But we got over that quite quickly, and we tend to do things more naturally these days.

Has your approach to writing changed as the musical tools available to you have evolved?

Gore: This time around, it was actually very different from the way we worked in the past. I've always worked on the demos on my own, in my studio at home. This time around, I had six months where I basically did nothing. I just kept putting it off and putting it off: "I'm not inspired. I don't feel like I've got the songs in me." It became a real chore. So I decided, for the first time, to get a couple of friends in, just to kick-start me. I got Gareth Jones, an engineer we've worked with quite a bit in the past, to come in and work with me, and one of my friends, Paul Freegard, who's sort of a keyboard programmer.

Just having them there made me start writing. They would sit in the studio, waiting to work, so I'd say, "Give me two hours and I'll come back with a song that we can start on." That was really important for me. Had I not had them there, I think I would have just kept putting it off. Even though I had the rest of the band dying to work, and the record company desperate for us to start putting something out, that meant nothing until I had two people sitting in the studio, waiting to work.

Do you still write both on guitar and on keys?

Gore: I generally start either on acoustic guitar or on piano, just to get the chord structure and the words and the vocal melody together before I even think about where I'm going to take the song.

So you don't hear the arrangement, or think about the instruments you'd like to use, when you're writing?

Gore: I don't work like that. It's really trial and error with me. We worked with Mark Bell, who's probably most famous for the last couple of records he worked on with Bjork ['Homogenic' and 'Selma Songs']. He's just so good with sounds. He can visualize sounds in his head. He goes to a keyboard, and he creates that sound. It's not even just about the keyboard sound - it's the whole vision of a song. I just can't do that. I really have to test something out. If it works, keep it in; if it doesn't, take it out.

Can you point to a song on 'Exciter' that might have gone in a very different direction without Mark's input on arrangements?

Fletcher: 'I Feel Loved' is a good example.

Gore: 'I Feel Loved' had a dance theme to it. It was already hinting at a dance-floor thing. But when I actually did the demo, I think it was about 109 beats per minute, and Mark sped it up to 128. We got in a percussion player, and it ended up sounding like Hamilton Bohannon [laughs]. Even though the basic song is quite similar [to the demo], it's definitely taken on a different meaning. Apart from that, Mark added this really great [TC Works] Mercury. There are all these great virtual synths at the moment, but the Mercury is fantastic. Mark used it to get that aggressive, growly sound over the top, that really took it somewhere else.

'I Feel Loved' is one of the few songs on 'Exciter' that has a steady backbeat feel.

Gore: I think it's the only track on the album that actually might get played in a club. It makes me laugh when people say we're a dance band. I can't remember the last time we did anything that might be aimed at the dance floor, apart from the occasional remix. They used to put stickers on our albums that said, "Dance Record". I don't know how long that went on...

Fletcher: 'I Feel You' [from 'Songs of Faith and Devotion', 1993] had that.

Gore: The first three or four albums had that, and it used to make me laugh.

On 'I Feel Loved' the steady rhythm seems to tie the song together through its many textural changes.

Gore: The whole album is very diverse. I think it's okay for us now, 21 years after we started, to actually embrace disco and say that we feel comfortable putting out a record that has four on the floor. There probably would have been a point in the past where we would have shied away from that.

By the same token, the guitar sounds on 'Exciter' work within the electronic timbres of each song as an orchestrational element.

Gore: One of the things about Mark [Bell] is, we've done albums in the past where we'd be working on trying to get something like that over two days. But Mark's got a very relaxed attitude toward the guitar sounds. Perhaps that's why it sounds like that.

[Keyboard, May 2001, Words: Robert L. Doerschuk. Pictures: Anton Corbijn.]

Specialist interview looking in close detail at the studio technicalities of the making of Exciter. Most of the album's songs are examined down to the intricacies of how certain sounds were made, and Martin and Andy discuss their working processes and the equipment and software used. Producer Mark Bell is also briefly interviewed. Although the average reader will probably lose interest half way through, this article is outstanding for musicians.

" I think we were considered circus freaks, really, out on a limb somewhere, doing something that had no emotion and was absolutely cold. But we never, ever, considered it that way at all. We've managed to get a lot of emotion out of samplers and synthesizers. "

Back in 1980, when the prototype version of Depeche Mode took form in Basildon, England, eagle-eyed British journalists looked them over and decided they fit into the trendy New Romantic sub-genre, though some punk residue cast a shadow or two over their look and sound. What made them different was their commitment to dragging synthesizers away from the sterile dance-oriented pop of Kraftwerk into a more song-driven, mainstream context.

That was a lifetime ago. In the intervening decades they've released 14 albums, the most recent, 'Ultra', in 1997. That's a substantial body of creative work, and the band can boast more than a few chart-surfing hits. Yet, aside from the sheer endurance, what may impress fans most about these guys is the fact that through the long parade of trends in pop music, they've kept their sound intact and vital.

Need proof? Flash back to 1983, after co-founder Vince Clarke packed up his peppy sequences and split to form Yaz. The band is riding high with 'Everything Counts'. Now kidnap some unsuspecting fans from the local vinyl shop, zoom them to the present, and play them parts of 'Exciter', the milky drones and slithery, slow-mo synth lines of 'Shine', or the Munster-like, lead-footed plod from 'Dead of Night'. Whatever track you pick, your victims will flash a knowing look and say, "So, you got the new Depeche Mode."

Rather than get lost in a struggle to reinvent themselves, this band - like Louis Armstrong, the Stones, and Philip Glass - has made it their mission to keep doing what they do best, and to do it better than ever. 'Exciter', with its unsettling chord changes, darkly glistening timbres, inexpressive yet somehow affecting vocals, and allergy to punchy backbeats, argues that they've succeeded once again.

You say they're stagnating? Standing still? Not for a minute. They're being true to their vision. In spirit, Depeche Mode is an artifact dating back to a time when electronic pop was new, when the artists who explored it were drawn more by its potential than by any instinct to conform. They've influenced many, particularly in ambient circles, yet no one has put all the pieces together - the craft of their songs, the experimental spirit of their arrangements - with as much consistency and originality as Depeche Mode themselves.

We explored these issues one afternoon in March with two thirds of Depeche Mode, Andrew Fletcher and Martin Gore. A few days later, 'Exciter' producer Mark Bell agreed to answer email questions about his involvement and perspective on the project; his thoughts appear on page 38.

Does 'Exciter' have any particular identity for you, as you consider it in the context of your catalog?

Gore: This record is far too close at the moment. We've been working on it for the last year and a half. I still find it really hard to judge any of our records. We just work on them far too much, and play them far too much. We're the last persons you should ask, with the least perspective.

Fletcher: For us, we remember distinct periods of our career that stick out. But we don't really conceptualize too much. We do things very naturally. When we started out, the electronic purists said there were rules we had to stick to. We didn't really use guitars, even though the guitar was my first instrument; I started playing it when I was 13. I hadn't even attempted keyboards until I was at least 16 or 17. But we got over that quite quickly, and we tend to do things more naturally these days.

Has your approach to writing changed as the musical tools available to you have evolved?

Gore: This time around, it was actually very different from the way we worked in the past. I've always worked on the demos on my own, in my studio at home. This time around, I had six months where I basically did nothing. I just kept putting it off and putting it off: "I'm not inspired. I don't feel like I've got the songs in me." It became a real chore. So I decided, for the first time, to get a couple of friends in, just to kick-start me. I got Gareth Jones, an engineer we've worked with quite a bit in the past, to come in and work with me, and one of my friends, Paul Freegard, who's sort of a keyboard programmer.

Just having them there made me start writing. They would sit in the studio, waiting to work, so I'd say, "Give me two hours and I'll come back with a song that we can start on." That was really important for me. Had I not had them there, I think I would have just kept putting it off. Even though I had the rest of the band dying to work, and the record company desperate for us to start putting something out, that meant nothing until I had two people sitting in the studio, waiting to work.

Do you still write both on guitar and on keys?

Gore: I generally start either on acoustic guitar or on piano, just to get the chord structure and the words and the vocal melody together before I even think about where I'm going to take the song.

So you don't hear the arrangement, or think about the instruments you'd like to use, when you're writing?

Gore: I don't work like that. It's really trial and error with me. We worked with Mark Bell, who's probably most famous for the last couple of records he worked on with Bjork ['Homogenic' and 'Selma Songs']. He's just so good with sounds. He can visualize sounds in his head. He goes to a keyboard, and he creates that sound. It's not even just about the keyboard sound - it's the whole vision of a song. I just can't do that. I really have to test something out. If it works, keep it in; if it doesn't, take it out.

Can you point to a song on 'Exciter' that might have gone in a very different direction without Mark's input on arrangements?

Fletcher: 'I Feel Loved' is a good example.

Gore: 'I Feel Loved' had a dance theme to it. It was already hinting at a dance-floor thing. But when I actually did the demo, I think it was about 109 beats per minute, and Mark sped it up to 128. We got in a percussion player, and it ended up sounding like Hamilton Bohannon [laughs]. Even though the basic song is quite similar [to the demo], it's definitely taken on a different meaning. Apart from that, Mark added this really great [TC Works] Mercury. There are all these great virtual synths at the moment, but the Mercury is fantastic. Mark used it to get that aggressive, growly sound over the top, that really took it somewhere else.

'I Feel Loved' is one of the few songs on 'Exciter' that has a steady backbeat feel.

Gore: I think it's the only track on the album that actually might get played in a club. It makes me laugh when people say we're a dance band. I can't remember the last time we did anything that might be aimed at the dance floor, apart from the occasional remix. They used to put stickers on our albums that said, "Dance Record". I don't know how long that went on...

Fletcher: 'I Feel You' [from 'Songs of Faith and Devotion', 1993] had that.

Gore: The first three or four albums had that, and it used to make me laugh.

On 'I Feel Loved' the steady rhythm seems to tie the song together through its many textural changes.

Gore: The whole album is very diverse. I think it's okay for us now, 21 years after we started, to actually embrace disco and say that we feel comfortable putting out a record that has four on the floor. There probably would have been a point in the past where we would have shied away from that.

By the same token, the guitar sounds on 'Exciter' work within the electronic timbres of each song as an orchestrational element.

Gore: One of the things about Mark [Bell] is, we've done albums in the past where we'd be working on trying to get something like that over two days. But Mark's got a very relaxed attitude toward the guitar sounds. Perhaps that's why it sounds like that.

Last edited: