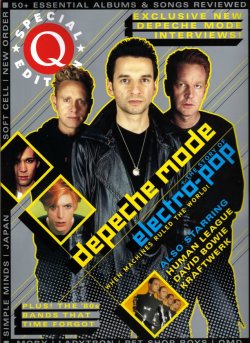

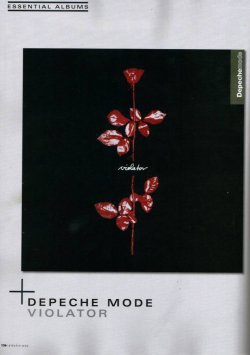

Depeche Mode Violator (Essential Albums)

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Toby Manning.]

A review of Violator which manages to be glowing and eloquent while keeping its feet on the ground. The author at times almost falls into familiar pitfalls (Martin's black ancestry, Martin writing about Dave), but overall this is very worthwhile as it throws some new light on a much loved album we thought we already knew.

Violator has to be one of the most unlikely Ecstasy albums ever made. Yet Despite Depeche Mode consuming copious quantities of the stuff during its making, the drug is the album’s motor. Right down, paradoxically, to its gloom, as songwriter Martin Gore suffered such unbearable comedowns that it coloured his entire creative process.

While Ecstasy may have induced uncharacteristic behaviour elsewhere – camaraderie on the football terraces; topless British men hugging each other; white males dancing – in Depeche Mode’s case it simply enhanced what was already present. The band, seemingly divorced from the acid house revolution then in full swing in the UK, had recently discovered they were dance music heroes, hugely influential on the Detroit techno scene. Indeed, when they’d visited the city, this whitest and uncoolest of bands had been mobbed by black techno fans. [1] This experience led them to employing house producer Francois Kevorkian to mix their album, buffing their extant dance elements up with a contemporary techno sheen.

Equally, Violator’s dark muscularity was part of a process that began with 1983’s proto-industrial Construction Time Again, found its feet with Black Celebration, adding guitars to the mix on 1987’s Music For The Masses, and now gained additional grit with the employment of goth / industrial producer Flood (Soft Cell, Nine Inch Nails). All of which points to the fact that Violator is Depeche Mode in excelsis: the distillation of their craft, with Ecstasy the emulsifier. Furthermore, their amped-up, arena-friendly sound, gothic wordplay – and, naturally, the new guitars – chimed with the American audience they had been tirelessly targeting. Gahan, with some bemusement, observed, “All of a sudden it’s cool to like Depeche Mode.” Nevertheless, despite the huge success of their 101 tour, theirs was still perceived as an underground success. Violator would change all that.

Recorded in a variety of studios in Italy, Denmark, and the UK, the Violator sessions got off to a bad start in Milan as partying overtook recording. The first signs that the band’s hedonism might become a problem started to become apparent: Gahan’s behaviour was particularly erratic, while Andy Fletcher’s hypochondria and compulsions hit critical mass, culminating in him fleeing to check himself into rehab clinic The Priory.

All this uncertainty – topped off with those Ecstasy comedowns – may account for lyrics that distil Gore’s angst-ridden concerns: religion (Personal Jesus), sex (Blue Dress) and guilt (Halo). Precision-tailored to the music (assisted by the perfect diction of Gahan and Gore himself), Gore clusters rhyme upon rhyme without ever sounding forced: “When I need a drug in me / and it brings out the thug in me / feel something tugging me.” These lyrics – from The Sweetest Perfection – clearly refer to Gahan, who had begun to show drug-induced personality changes, to become, in Fletcher’s words, more of “a spanner”: in Milan he’d randomly picked a fight with 10 local youths.

As for the music, the trailer single in late ’89, Personal Jesus, announced Depeche Mode’s ever more muscular, guitar-oriented intent. The song contains hints of blues and glam in its brutally simple riff and stomping rhythm, the former perhaps not related to Gore’s shock discovery just prior to the sessions that his father was black [2]; the latter probably the result of the glam tendencies on Gore’s covers album, Counterfeit, recorded earlier that year. The song would later be very effectively covered by Johnny Cash.

The album itself opens in purposeful fashion: World In My Eyes shows off Depeche Mode’s new dancey facility, with its propulsive beat and techno polyrhythms. Despite being the only track not mixed by Kevorkian, Enjoy The Silence is dancier still: a four-to-the-floor full-fat disco pump that invokes a darker, gothier New Order (as if in acknowledgement, the Violator tour would feature New Order side-project Electronic as support). It would become their biggest American hit. Policy Of Truth would be another substantial hit, another dance floor stormer featuring horns, slithering bass, abrasive guitars and – harmonised by Gahan and Gore – a contrastingly wistful, slightly melancholy melody. Even more haunting, Waiting For The Night’s bed of pulsing synths prefigures dance duo Leftfield’s 1992 epic Song Of Life.

The album ends on two brooding ballads: Blue Dress – sung, like Sweetest Perfection, by Gore – seemingly reflecting on the simplicity of male sexuality; and Clean, a bass-heavy, Pink Floyd-ian throbber, its title gaining resonance in the light of Gahan’s heroin addiction. He gives the song the album’s most powerful vocal, stretching from bass boom to high yearning keen. It’s a bleak, commanding end to a colossal album.

Violator went on to sell seven million copies and helped create the dominant ethos of “Alternative” for the next decade: arena-sized gothic angst, decadence and drugs. As such, Violator’s success opened up mainstream space for explicitly Mode-influenced groups like Nine Inch Nails and for grunge.

Gore says, “I think Violator’s probably up there with our best album, so if I can do something like that again I’d be very happy.” Happy? Judging by the effect Ecstasy had on him, happiness is not something that comes easily to Gore. Nor indeed, when gloom produces something as glorious as Violator, anything you’d wish upon him.

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Toby Manning.]

A review of Violator which manages to be glowing and eloquent while keeping its feet on the ground. The author at times almost falls into familiar pitfalls (Martin's black ancestry, Martin writing about Dave), but overall this is very worthwhile as it throws some new light on a much loved album we thought we already knew.

" Violator is Depeche Mode in excelsis: the distillation of their craft, with Ecstasy the emulsifier. "

Violator has to be one of the most unlikely Ecstasy albums ever made. Yet Despite Depeche Mode consuming copious quantities of the stuff during its making, the drug is the album’s motor. Right down, paradoxically, to its gloom, as songwriter Martin Gore suffered such unbearable comedowns that it coloured his entire creative process.

While Ecstasy may have induced uncharacteristic behaviour elsewhere – camaraderie on the football terraces; topless British men hugging each other; white males dancing – in Depeche Mode’s case it simply enhanced what was already present. The band, seemingly divorced from the acid house revolution then in full swing in the UK, had recently discovered they were dance music heroes, hugely influential on the Detroit techno scene. Indeed, when they’d visited the city, this whitest and uncoolest of bands had been mobbed by black techno fans. [1] This experience led them to employing house producer Francois Kevorkian to mix their album, buffing their extant dance elements up with a contemporary techno sheen.

Equally, Violator’s dark muscularity was part of a process that began with 1983’s proto-industrial Construction Time Again, found its feet with Black Celebration, adding guitars to the mix on 1987’s Music For The Masses, and now gained additional grit with the employment of goth / industrial producer Flood (Soft Cell, Nine Inch Nails). All of which points to the fact that Violator is Depeche Mode in excelsis: the distillation of their craft, with Ecstasy the emulsifier. Furthermore, their amped-up, arena-friendly sound, gothic wordplay – and, naturally, the new guitars – chimed with the American audience they had been tirelessly targeting. Gahan, with some bemusement, observed, “All of a sudden it’s cool to like Depeche Mode.” Nevertheless, despite the huge success of their 101 tour, theirs was still perceived as an underground success. Violator would change all that.

Recorded in a variety of studios in Italy, Denmark, and the UK, the Violator sessions got off to a bad start in Milan as partying overtook recording. The first signs that the band’s hedonism might become a problem started to become apparent: Gahan’s behaviour was particularly erratic, while Andy Fletcher’s hypochondria and compulsions hit critical mass, culminating in him fleeing to check himself into rehab clinic The Priory.

All this uncertainty – topped off with those Ecstasy comedowns – may account for lyrics that distil Gore’s angst-ridden concerns: religion (Personal Jesus), sex (Blue Dress) and guilt (Halo). Precision-tailored to the music (assisted by the perfect diction of Gahan and Gore himself), Gore clusters rhyme upon rhyme without ever sounding forced: “When I need a drug in me / and it brings out the thug in me / feel something tugging me.” These lyrics – from The Sweetest Perfection – clearly refer to Gahan, who had begun to show drug-induced personality changes, to become, in Fletcher’s words, more of “a spanner”: in Milan he’d randomly picked a fight with 10 local youths.

As for the music, the trailer single in late ’89, Personal Jesus, announced Depeche Mode’s ever more muscular, guitar-oriented intent. The song contains hints of blues and glam in its brutally simple riff and stomping rhythm, the former perhaps not related to Gore’s shock discovery just prior to the sessions that his father was black [2]; the latter probably the result of the glam tendencies on Gore’s covers album, Counterfeit, recorded earlier that year. The song would later be very effectively covered by Johnny Cash.

The album itself opens in purposeful fashion: World In My Eyes shows off Depeche Mode’s new dancey facility, with its propulsive beat and techno polyrhythms. Despite being the only track not mixed by Kevorkian, Enjoy The Silence is dancier still: a four-to-the-floor full-fat disco pump that invokes a darker, gothier New Order (as if in acknowledgement, the Violator tour would feature New Order side-project Electronic as support). It would become their biggest American hit. Policy Of Truth would be another substantial hit, another dance floor stormer featuring horns, slithering bass, abrasive guitars and – harmonised by Gahan and Gore – a contrastingly wistful, slightly melancholy melody. Even more haunting, Waiting For The Night’s bed of pulsing synths prefigures dance duo Leftfield’s 1992 epic Song Of Life.

The album ends on two brooding ballads: Blue Dress – sung, like Sweetest Perfection, by Gore – seemingly reflecting on the simplicity of male sexuality; and Clean, a bass-heavy, Pink Floyd-ian throbber, its title gaining resonance in the light of Gahan’s heroin addiction. He gives the song the album’s most powerful vocal, stretching from bass boom to high yearning keen. It’s a bleak, commanding end to a colossal album.

Violator went on to sell seven million copies and helped create the dominant ethos of “Alternative” for the next decade: arena-sized gothic angst, decadence and drugs. As such, Violator’s success opened up mainstream space for explicitly Mode-influenced groups like Nine Inch Nails and for grunge.

Gore says, “I think Violator’s probably up there with our best album, so if I can do something like that again I’d be very happy.” Happy? Judging by the effect Ecstasy had on him, happiness is not something that comes easily to Gore. Nor indeed, when gloom produces something as glorious as Violator, anything you’d wish upon him.

[1] - This article examines their visit to Detroit and their effect on house music in more detail.

[2] - I'm not so sure about this. As I understand it, Martin only found out about his real father's ethnicity in 1991, when he was expecting his first child: his mother told him at this point to pre-empt any possible surprises when the baby was born. As to the assumption that if Martin's music sounds black, that must be because of his black DNA more than any other influences, Martin's musical vocation began when he came across a stack of 1950s records in his mother's cupboard and was instantly hooked. A few years ago, an otherwise good article in Revolver gave in to the temptation to play up the race aspect in this way, and the ludicrous conclusion (Goodnight Lovers as a "racial lament", anyone? - thought not), for me, lost the article a lot of credibility. By contrast, in the next sentence the author passes without comment over Martin's glam influences, evidently on the assumption that he grew up with them.