You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

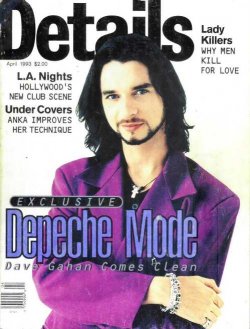

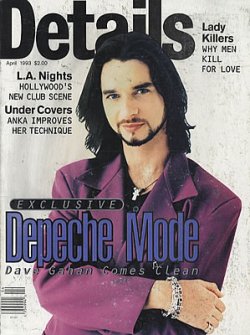

Depeche Mode In The Mode (Details, 1993)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1993 details in the mode

A detailed interview in which all the band members get the opportunity to speak candidly about both the making of Songs Of Faith And Devotion and the changes in their personal lives. I never understood Dave's perspective on his first divorce until I read what he has to say here. At times the interviewer's approach can become uncomfortable as he doesn't quite seem to know when to leave a sensitive matter alone, but overall the band open up considerably, making for a rewarding read.

" “I hope,” Gahan tells me, “that Joanne falls in love and she can be as happy in that area of life as I am, because then she’ll know and understand why I had to do it. It was for very selfish reasons.” "

Many thanks to Gina Gomez for kindly supplying the scans of this article.

Dave Gahan looks me over suspiciously. “I remember you reviewed one of our singles once,” he says. “Can’t remember if it was good or bad.” He escorts me into a playback room in London’s Olympic Studios to listen to seven of the tracks Depeche Mode have spent ten arduous months making. Dave tells me to sit between the two enormous speakers on the mixing desk, because that’s the best place to hear it. He doesn’t sit next to me; he’s heard it all a thousand times before. So I sit there alone and listen, scribbling notes, wondering what he would like me to say. Gahan is a bundle of nervous intensity, nodding his head in time to the music, scrutinizing me for a reaction.

When it’s over he asks me what I think of it.

I enthuse. I seem to pass the test. Gahan stands up, clutching a can of Budweiser, and says, “I was watching you and I could tell you got something.” He starts talking about this album, how it’s the best thing he’s been involved with, how it’s not been easy, about how it’s partly all wrapped up in stuff he’s been going through and partly to do with the way the world is at the moment. “It’s something that’s needed,” he tells me. “It’s a positive thing.”

For Dave Gahan, this album is therapy. The last few years have been strange and painful.

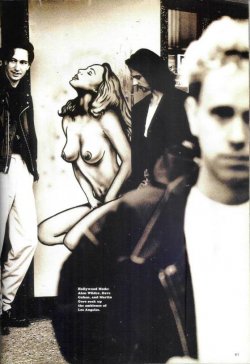

The album is pretty much finished. This is the third and final recording session. They started 1992 in Madrid, moved to Hamburg, and now they’re back in London. Today they’ve been finishing a rhythm track for “Rush”, a loose pounding of sequencers and guitars that’s a million miles from the clean electronic music they started out with thirteen years ago. Alan Wilder is concentrating on a screen full of numbers. Wearing a black woollen hat pulled down to his ears, Martin Gore sits in front of a mixing desk with Flood, the producer who worked with the group on their 1990 LP, Violator. Occasionally Andy Fletcher, who doesn’t have much to do with the music at this stage, sticks his head in to see how it’s going. Two weeks more and it’s all over.

Depeche Mode know that after a very long while they are teetering on the brink of something very large indeed. Each time they release a record they sell more, moving on from being the odd English cult artists who went Top 20 in the U.S. in 1984 with “People Are People” to filling stadiums and selling six million copies of Violator.

Dave Gahan has changed since Violator. Visually he is unrecognisable. That, originally, was the point. After the tour he needed a break. He moved to Los Angeles and grew his hair to his shoulders and made the goatee he’s flirted with in the past a more permanent fixture. He began to prefer people calling him David, though no-one really does. He started listening to Jane’s Addiction, Soundgarden, and Neil Young. “Now I’m just a total and absolute Neilhead.”

The biggest difference is in the way he acts. Before, he shared his other band members’ diffidence; now, he’s self-possessed and hyperactive with enthusiasm. I’m so amazed at the transformation that I tell him so. He lowers his voice and says, “Every single aspect of my life has changed in the last couple of years. Everything. I’d like to think that I’m a much better person than I was before.” He looks me in the eye. “I’ve been through a lot of stuff, William.”

A lot of things have happened to Dave Gahan. He comes from Basildon, a postwar town twenty miles northeast of London, significantly off the tourist maps and, in the late ‘70s, brim full of bored teenagers scuffling on the streets. Dave Gahan was one of them. His dad left home when he was about six months old, returning only briefly for a few years when Dave was seven, after his stepfather died. In Gahan’s early teenage years he got into what he describes as “a dodgy phase” stealing motorbikes; it was just what boys did in that part of Basildon. He was saved from getting into anything worse when he met Vince Clarke, Andy Fletcher, and Martin Gore, from the other, nicer side of town. The three of them were in a group called Composition Of Sound and played synthesizers. Painfully aware of a lack of charisma, they knew they needed a frontman. One day they turned up to rehearse in the local scout hall and heard Gahan running through a version of David Bowie’s “Heroes” with another band.

Depeche Mode’s first champion, producer Daniel Miller, used to be a film editor. He had a minor late-‘70s hit with “T.V.O.D.”, a primitive electronic single, so he formed his own label, Mute, and started releasing synth-pop cover versions under the banner of Silicon Teens. When he came across four real teenagers playing sweetly harmonized electronic music in a pub in east London, it was too good to be true.

It was 1981, the year of the British New Romantic movement. In those days Dave Gahan wore baggy suits and cute bow ties. A neatly coiffured New Romantic fringe drooped in front of his eyes and a stud shone from his pierced nose. Depeche Mode had a couple of hits, became pinups, and seemed to be nothing more than microprocessed bubblegum. But by the end of the year Vince Clarke, the band’s songwriter, had left (to form Yaz and, later, Erasure), and Martin took over. Gore began spending time in Berlin and, though he downplays it, was inspired by industrial noisemakers like Einsturzende Neubaten. Subsequently, Depeche Mode fashioned a harder electronic backdrop for Gore’s increasingly sophisticated songs about teenage suicide and twisted romanticism.

By the middle of the decade, Gahan too had undergone a transformation. He was no longer the slight teenager who on the group’s first tour had stood awkwardly onstage, waiting for somebody to cue up the backing tapes. Now he had a new stage routine, full of pirouettes, kicks, mike stand swinging, and sweat. Audiences began to swoon for his wiggling, leather-clad bottom.

At the time, Dave was going out with a Basildon girl named Joanne. For a while she ran the Mode fan club. In 1985 they married. In 1987 they had a son, Jack. In 1991 they started getting divorced.

Dave Gahan sits on the sofa in the studio. He wants to talk about the new album, about the divorce and his new marriage, about why everything is better now. “You start out with all the right intentions when you’re in a band, and it’s not that you lose those ideals – you just get wrapped up in the band. I thought it was time to readdress my life because there were aspects of it that were just so wrong and I had to change.”

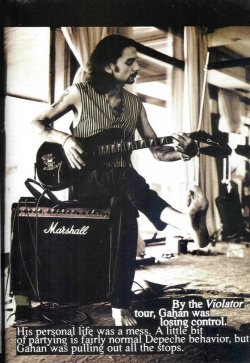

By the Violator tour, Gahan was losing control. His personal life was a mess. A little bit of partying is fairly normal Depeche behaviour, but Gahan was pulling out the stops. The rest of the band were becoming worried. “I think he just felt that performing was the only thing he could do right,” Andy Fletcher remembers. “He was very emotional with all of us. I personally tended to steer clear of him.”

For years Dave’s marriage was falling into the familiar boy-marries-girl-becomes-rock-god trap. He was sleeping around on the road. A lot. He felt awful about it, but he couldn’t make himself stop. “You make yourself blind and you go out there. It’s great to meet lots of different girls and have fun, but then you realise what a shit you are and how you’re destroying other people’s lives – or life – with it.”

Last edited:

Did you feel guilty about it?

He groans and smiles self-consciously. “Absolutely. And it had been building up for years. I think…” He pauses. “Well, I know, well… I think pretty much I know… that my wife, my previous wife, was completely faithful to me. And I’d go back to her and… not lie, because Joanne wouldn’t even ask me things.”

Presumably she suspected.

“I’m sure she did. She wasn’t stupid.”

Things came to a head in 1990 when Gahan fell in love. Teresa Conroy was a publicist who’d worked for producer Rick Rubin. In 1988 she worked on Depeche Mode’s Music For The Masses tour. In those days she had bleached-blonde hair and wore punky clothes. She travelled with the band, setting up interviews and ticket giveaways on local radio stations. After the tour, Gahan headed back to Joanne and Jack in England. But during ’89, when he was in Milan recording Violator, he’d call Teresa up, often drunk, and talk about what he was doing.

They met again at rehearsals for the Violator tour. Gahan realized he had fallen in love with Teresa, and it was like being smashed on the head with a hammer. “You look at yourself in the mirror one morning and suddenly everything’s very, very different and the whole perspective has suddenly changed. Last night wasn’t just ‘I wanted to get laid’ – I didn’t want to be that person anymore. Teresa brought out some emotions in me that I hadn’t discovered, like love,” he says, touchingly.

I remind him he once said that even though he sang about love, he didn’t fall in love himself.

He thinks for a bit and then says, “Well, I think I was just denying my true feelings a lot of the time, having to lie my way through a lot of my life with people I was supposed to respect and love and care for. So I blew that completely.”

The new LP is Depeche Mode’s Joshua Tree, the moment when a cult band transforms itself with a loud declaration of self-confidence. There are still moments of minor key introversion, like in the sinister love song “In Your Room”, but much of it is rich, loud, bluesy, electronic rock. Dave Gahan’s increasing influence on the group is clear in the euphoric stadium rock of “Rush”. And there are spirituals like “Get Right With Me”, complete with gospel choir, and “Higher Love”, which Fletch appositely describes as “our Tears For Fears number”. Plus the low-key Martin Gore moment, where he steps out of the shadows and sings the ballad “One Caress” to a ringing string arrangement.

The new album is called Songs Of Faith And Devotion. It’s not the first time Martin has revelled in his love for religious imagery, but the record might also be about the last few years of Dave Gahan’s life. Gore denies that he actually wrote the album for Gahan’s situation, but its themes of love and salvation fit pretty well. In 1991 Martin became a father. Since then, he says, his songs are more “uplifting and positive”. In the words of the ever-pragmatic Andy Fletcher, the new songs are “a bit more emotional and less pervy”.

Seven years ago, I sat next to Fletcher at a meal. He was fretting about the future. “When Martin stops writing songs,” he said, “it’s all over.” It was as if he were worried that because Gore’s songwriting talent had emerged so miraculously, apparently from nowhere, that it might suddenly disappear. Martin was sitting across the table, drinking. Someone from his record company leaned over and warned that any minute now Martin was going to start taking his clothes off. “He does that when he’s drunk,” she insisted.

Martin Gore is a strange, elusive man. “I was probably a weird child,” he says, and you perch on the edge of your seat to hear just how weird he was. Then he says, “Because I quite liked school and stuff.”

He groans and smiles self-consciously. “Absolutely. And it had been building up for years. I think…” He pauses. “Well, I know, well… I think pretty much I know… that my wife, my previous wife, was completely faithful to me. And I’d go back to her and… not lie, because Joanne wouldn’t even ask me things.”

Presumably she suspected.

“I’m sure she did. She wasn’t stupid.”

Things came to a head in 1990 when Gahan fell in love. Teresa Conroy was a publicist who’d worked for producer Rick Rubin. In 1988 she worked on Depeche Mode’s Music For The Masses tour. In those days she had bleached-blonde hair and wore punky clothes. She travelled with the band, setting up interviews and ticket giveaways on local radio stations. After the tour, Gahan headed back to Joanne and Jack in England. But during ’89, when he was in Milan recording Violator, he’d call Teresa up, often drunk, and talk about what he was doing.

They met again at rehearsals for the Violator tour. Gahan realized he had fallen in love with Teresa, and it was like being smashed on the head with a hammer. “You look at yourself in the mirror one morning and suddenly everything’s very, very different and the whole perspective has suddenly changed. Last night wasn’t just ‘I wanted to get laid’ – I didn’t want to be that person anymore. Teresa brought out some emotions in me that I hadn’t discovered, like love,” he says, touchingly.

I remind him he once said that even though he sang about love, he didn’t fall in love himself.

He thinks for a bit and then says, “Well, I think I was just denying my true feelings a lot of the time, having to lie my way through a lot of my life with people I was supposed to respect and love and care for. So I blew that completely.”

The new LP is Depeche Mode’s Joshua Tree, the moment when a cult band transforms itself with a loud declaration of self-confidence. There are still moments of minor key introversion, like in the sinister love song “In Your Room”, but much of it is rich, loud, bluesy, electronic rock. Dave Gahan’s increasing influence on the group is clear in the euphoric stadium rock of “Rush”. And there are spirituals like “Get Right With Me”, complete with gospel choir, and “Higher Love”, which Fletch appositely describes as “our Tears For Fears number”. Plus the low-key Martin Gore moment, where he steps out of the shadows and sings the ballad “One Caress” to a ringing string arrangement.

The new album is called Songs Of Faith And Devotion. It’s not the first time Martin has revelled in his love for religious imagery, but the record might also be about the last few years of Dave Gahan’s life. Gore denies that he actually wrote the album for Gahan’s situation, but its themes of love and salvation fit pretty well. In 1991 Martin became a father. Since then, he says, his songs are more “uplifting and positive”. In the words of the ever-pragmatic Andy Fletcher, the new songs are “a bit more emotional and less pervy”.

Seven years ago, I sat next to Fletcher at a meal. He was fretting about the future. “When Martin stops writing songs,” he said, “it’s all over.” It was as if he were worried that because Gore’s songwriting talent had emerged so miraculously, apparently from nowhere, that it might suddenly disappear. Martin was sitting across the table, drinking. Someone from his record company leaned over and warned that any minute now Martin was going to start taking his clothes off. “He does that when he’s drunk,” she insisted.

Martin Gore is a strange, elusive man. “I was probably a weird child,” he says, and you perch on the edge of your seat to hear just how weird he was. Then he says, “Because I quite liked school and stuff.”

Last edited:

Martin Gore is that sort of weird.

He came from a working-class background, the other side of Basildon from Dave Gahan. At Nicholas School, a large, grim public school, he was a likeable boy who liked to do the right thing. Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher went to the same school, as did Alison Moyet, who later formed Yaz with Clarke, and Perry Bamonte, keyboard player with The Cure. Bamonte remembers Gore as “very, very introverted.” One typically Gore-esque incident occurred five minutes before the bell rang in math. Bamonte was begging Martin to let him look at his answers so he could copy them. Gore turned each time he asked and looked blankly at him. “He just flatly refused,” says Bamonte. “It wasn’t the done thing.”

At thirteen, he was given an acoustic guitar, and he played it to death, He enjoyed being alone. “I didn’t use to go out very much between about sixteen and eighteen; I actually gave up drink for two years.” When Depeche Mode were having their first U.P. success with Vince Clarke’s bright electro-pop songs, Martin was still Mr. Ordinary working diligently at a local bank and going to church at the local Methodist chapel. It was only when their songwriter Clarke quit the band after their first album that Gore was thrust into the role of Depeche Mode songwriter and suddenly started to turn out the strangely subversive pop songs that have become the backbone of the group.

Andy, his closest friend in the band, admits that he doesn’t really see the connection between Martin and his songs. “He’s a really normal person. He likes to drink, he likes playing football, he likes really normal things, yet when he gets into a creating mode he seems to come up with these wonderful songs which make him this hero in some people’s eyes. It does amaze me; there’s nothing in his background to illustrate why this should happen.”

Gahan, more naturally extroverted, once put forward the theory that a lot of it came from the fact that Gore had missed out on his teens. When Gahan was out stealing motorbikes, Gore was up in his bedroom strumming Simon and Garfunkel songs.

The best Gore songs are about relationships. His words and melodies can be deceptively simple, but they celebrate the abnormality of love, treading the line between darkness and a camp humour. “Strangelove” and “Enjoy The Silence” revel in a claustrophobic subservience to love; “Little 15” and “A Question Of Time” look at innocence on the edge of corruption; “Master And Servant” and “Behind The Wheel” deal with the imagery of submission.

Gore is horrified by the ideas people get about him. He laughs nervously. “I should imagine from reading the lyrics,” he ventures, “they’d think I was dark and moody with quite a perverted sense of things.” He speaks with the slightest of lisps.

Gore’s least favourite subject is himself. He looks pained when he’s asked to talk about it. He sighs and shakes his head. If you ask him where he gets all these sexual power images, he comes to a shuddering, embarrassed halt and puts on his ‘next question’ face. His least favourite question of all time is whether “Master And Servant” has an autobiographical element. He blurts, “That was used metaphorically!”

But don’t songs like that make people wonder if you’re interested in that sort of sexuality?

“It comes up so often in songs that I must be,” Martin answers flippantly.

Do you practise it?

“What do you mean by ‘that sort of sexuality’? Where you put yourself in dominant or submissive roles?”

Yes.

Martin answers briefly, “I think that’s personal stuff, really.”

Are you interested in pornography?

He exhales. “Yeah.” Pause. “If it’s well done. It always amazes me that so much pornography is done badly. If it’s done well…” He trails off. “You have to choose your words carefully here, you’re always treading on dodgy ground.”

In the mid-‘80s, fetish clubs became fashionable in London. “I used to go,” Gore acknowledges. “I do like the imagery. I found that the atmosphere in those clubs was very friendly. I’m sure I did get some ideas from going to those kinds of places. Around that time, much to the disquiet of Gahan, Gore started wearing black nail polish, lipstick, pearl and rhinestone necklaces, and black leather miniskirts onstage.

When was the first time you wore one?

Martin scowls.

You hate that question deeply, I say.

“That’s because it gets brought up in every single interview.”

Do you like the idea of androgyny?

“I think so. Maybe it’s to do with my dislike of normality. I’ve always thought a macho image really boring.”

Does that lead to speculation that you’re gay?

“That is probably more universal. I think a lot of people think that I’m gay, which doesn’t offend me or worry me in the slightest. People can think what they like.”

He came from a working-class background, the other side of Basildon from Dave Gahan. At Nicholas School, a large, grim public school, he was a likeable boy who liked to do the right thing. Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher went to the same school, as did Alison Moyet, who later formed Yaz with Clarke, and Perry Bamonte, keyboard player with The Cure. Bamonte remembers Gore as “very, very introverted.” One typically Gore-esque incident occurred five minutes before the bell rang in math. Bamonte was begging Martin to let him look at his answers so he could copy them. Gore turned each time he asked and looked blankly at him. “He just flatly refused,” says Bamonte. “It wasn’t the done thing.”

At thirteen, he was given an acoustic guitar, and he played it to death, He enjoyed being alone. “I didn’t use to go out very much between about sixteen and eighteen; I actually gave up drink for two years.” When Depeche Mode were having their first U.P. success with Vince Clarke’s bright electro-pop songs, Martin was still Mr. Ordinary working diligently at a local bank and going to church at the local Methodist chapel. It was only when their songwriter Clarke quit the band after their first album that Gore was thrust into the role of Depeche Mode songwriter and suddenly started to turn out the strangely subversive pop songs that have become the backbone of the group.

Andy, his closest friend in the band, admits that he doesn’t really see the connection between Martin and his songs. “He’s a really normal person. He likes to drink, he likes playing football, he likes really normal things, yet when he gets into a creating mode he seems to come up with these wonderful songs which make him this hero in some people’s eyes. It does amaze me; there’s nothing in his background to illustrate why this should happen.”

Gahan, more naturally extroverted, once put forward the theory that a lot of it came from the fact that Gore had missed out on his teens. When Gahan was out stealing motorbikes, Gore was up in his bedroom strumming Simon and Garfunkel songs.

The best Gore songs are about relationships. His words and melodies can be deceptively simple, but they celebrate the abnormality of love, treading the line between darkness and a camp humour. “Strangelove” and “Enjoy The Silence” revel in a claustrophobic subservience to love; “Little 15” and “A Question Of Time” look at innocence on the edge of corruption; “Master And Servant” and “Behind The Wheel” deal with the imagery of submission.

Gore is horrified by the ideas people get about him. He laughs nervously. “I should imagine from reading the lyrics,” he ventures, “they’d think I was dark and moody with quite a perverted sense of things.” He speaks with the slightest of lisps.

Gore’s least favourite subject is himself. He looks pained when he’s asked to talk about it. He sighs and shakes his head. If you ask him where he gets all these sexual power images, he comes to a shuddering, embarrassed halt and puts on his ‘next question’ face. His least favourite question of all time is whether “Master And Servant” has an autobiographical element. He blurts, “That was used metaphorically!”

But don’t songs like that make people wonder if you’re interested in that sort of sexuality?

“It comes up so often in songs that I must be,” Martin answers flippantly.

Do you practise it?

“What do you mean by ‘that sort of sexuality’? Where you put yourself in dominant or submissive roles?”

Yes.

Martin answers briefly, “I think that’s personal stuff, really.”

Are you interested in pornography?

He exhales. “Yeah.” Pause. “If it’s well done. It always amazes me that so much pornography is done badly. If it’s done well…” He trails off. “You have to choose your words carefully here, you’re always treading on dodgy ground.”

In the mid-‘80s, fetish clubs became fashionable in London. “I used to go,” Gore acknowledges. “I do like the imagery. I found that the atmosphere in those clubs was very friendly. I’m sure I did get some ideas from going to those kinds of places. Around that time, much to the disquiet of Gahan, Gore started wearing black nail polish, lipstick, pearl and rhinestone necklaces, and black leather miniskirts onstage.

When was the first time you wore one?

Martin scowls.

You hate that question deeply, I say.

“That’s because it gets brought up in every single interview.”

Do you like the idea of androgyny?

“I think so. Maybe it’s to do with my dislike of normality. I’ve always thought a macho image really boring.”

Does that lead to speculation that you’re gay?

“That is probably more universal. I think a lot of people think that I’m gay, which doesn’t offend me or worry me in the slightest. People can think what they like.”

Last edited:

Downstairs in the studio canteen, the group is eating lasagne and talking end-of-album business. Alan Wilder is making the case for leading off the LP with “I Feel You”. Alan is the one who learned classical keyboards and played with go-nowhere groups like Daphne And The Tenderspots and The Hitmen before he answered the ad in the paper after Vince Clarke had left: “Name band, Synthesizer, must be under twenty-one.” He got the spot even though he was twenty-two. Wilder toured in ’82 and became an official member the following year. The eldest of the group at thirty-three, he sees himself as a pure musician. He writes symphonies in his sleep, though he can never quite remember them in the morning, and regards touring, promotion, and videos as a distraction from the studio. In the beginning he contributed a few B-side songs to Depeche Mode singles, but these days he leaves his writing to his side project, Recoil; he has produced an LP for Nitzer Ebb and will soon work with Curve.

Fletch appears, clutching a wad of CD packaging samples. He is the odd-job man, the group ambassador to the music industry, a regular reader of Billboard and The Economist. Infinitely sensible, he worked as an insurance clerk until he was sure that Depeche Mode were a going concern. As the years pass by, he’s less involved in music, the more he gets the management tasks. This hardly bothers him. “I take no interest in the making of the music,” Fletcher says.

He drops the CD samples on the table. “I don’t know which one’s best,” he says. “I don’t buy CDs. You have to tell me.”

Alan turns to me and says, by way of explanation, “He doesn’t listen to music.”

Fletch smiles and nods. He has a house by the Thames where he can fish in the river from his own garden and owns a stake in the restaurant. Like Gore, he had a daughter this year. In November he got married to his girlfriend, Grainne.

Fletcher tells the others he has budget proposals for the upcoming videos. “You got Anton’s?” asks Dave.

Over the last few years, photographer Anton Corbijn, who, like coproducer Flood, works closely with U2, has joined the group’s inner circle. He provides brilliantly moody images that allow the group to thrive in relative anonymity on video.

“How much?” asks Gahan.

“A hundred thousand,” says Fletch.

“Pounds or dollars?”

“Pounds.”

“Fucking hell,” Gahan exclaims.

“And it’s only black-and-white,” Fletch explains. Big laugh.

Many years ago I visited Depeche Mode at a studio in a small English village when they were recording “It’s Called A Heart.” [1] After Martin Gore has finished writing a song, I’d been told, he tends to get bored with the recording process. By the time I arrived, he was bored stupid. He told me that he and Andy would walk around the village streets, hoping someone would recognise them so he’d have someone to talk to.

Still, Martin is a big song fan. Though Depeche Mode are clearly among the progenitors of the industrial scene, he doesn’t like the formlessness of most noise music these days. He likes music that can bring him to tears. Songs by Leonard Cohen, John Lennon, Neil Young, and Kurt Weill when sung by Lotte Lenya.

On his and Fletch’s thirtieth birthdays Gore formed a group especially for their party. They were called the Sexist Boys and also featured Wayne Hussey from the Mission. In lipstick, wig, and beads, Gore played, “Hello Hello, I’m back again” by Gary Glitter, “Dancing Queen” by Abba, and “20th Century Boy” by T. Rex.

One of the elements he likes to include in his own songs is what he calls his “little twist”. In one of the more fragile songs, “Somebody”, he starts by dreaming up the perfect, all-enveloping lover, but right at the song’s climax he brings in the little twist and turns the tearjerker on its head. “Though things like this make me sick / In a case like this, I’ll get away with it.”

The story goes that he recorded “Somebody” in the nude. Is that true? I ask.

His guard comes up again. He frowns and says, “Er, yeah. I think it is, yeah,” as if it’s something he can’t clearly recall.

And did it make any difference?

“There was probably less rustling.” He laughs, suddenly and loudly.

When Depeche Mode began recording Songs Of Faith And Devotion in February of 1992, Dave Gahan had been living with Teresa in L.A. for most of the previous year. But a lot of 1991 was taken up with the divorce from Joanne. If that wasn’t enough, he heard one day that his estranged father had died. He had hardly known his father, but it seemed that connections with his past were disappearing. “In the space of six months,” he recalls, “everything just piled on top of me.”

Fletch appears, clutching a wad of CD packaging samples. He is the odd-job man, the group ambassador to the music industry, a regular reader of Billboard and The Economist. Infinitely sensible, he worked as an insurance clerk until he was sure that Depeche Mode were a going concern. As the years pass by, he’s less involved in music, the more he gets the management tasks. This hardly bothers him. “I take no interest in the making of the music,” Fletcher says.

He drops the CD samples on the table. “I don’t know which one’s best,” he says. “I don’t buy CDs. You have to tell me.”

Alan turns to me and says, by way of explanation, “He doesn’t listen to music.”

Fletch smiles and nods. He has a house by the Thames where he can fish in the river from his own garden and owns a stake in the restaurant. Like Gore, he had a daughter this year. In November he got married to his girlfriend, Grainne.

Fletcher tells the others he has budget proposals for the upcoming videos. “You got Anton’s?” asks Dave.

Over the last few years, photographer Anton Corbijn, who, like coproducer Flood, works closely with U2, has joined the group’s inner circle. He provides brilliantly moody images that allow the group to thrive in relative anonymity on video.

“How much?” asks Gahan.

“A hundred thousand,” says Fletch.

“Pounds or dollars?”

“Pounds.”

“Fucking hell,” Gahan exclaims.

“And it’s only black-and-white,” Fletch explains. Big laugh.

Many years ago I visited Depeche Mode at a studio in a small English village when they were recording “It’s Called A Heart.” [1] After Martin Gore has finished writing a song, I’d been told, he tends to get bored with the recording process. By the time I arrived, he was bored stupid. He told me that he and Andy would walk around the village streets, hoping someone would recognise them so he’d have someone to talk to.

Still, Martin is a big song fan. Though Depeche Mode are clearly among the progenitors of the industrial scene, he doesn’t like the formlessness of most noise music these days. He likes music that can bring him to tears. Songs by Leonard Cohen, John Lennon, Neil Young, and Kurt Weill when sung by Lotte Lenya.

On his and Fletch’s thirtieth birthdays Gore formed a group especially for their party. They were called the Sexist Boys and also featured Wayne Hussey from the Mission. In lipstick, wig, and beads, Gore played, “Hello Hello, I’m back again” by Gary Glitter, “Dancing Queen” by Abba, and “20th Century Boy” by T. Rex.

One of the elements he likes to include in his own songs is what he calls his “little twist”. In one of the more fragile songs, “Somebody”, he starts by dreaming up the perfect, all-enveloping lover, but right at the song’s climax he brings in the little twist and turns the tearjerker on its head. “Though things like this make me sick / In a case like this, I’ll get away with it.”

The story goes that he recorded “Somebody” in the nude. Is that true? I ask.

His guard comes up again. He frowns and says, “Er, yeah. I think it is, yeah,” as if it’s something he can’t clearly recall.

And did it make any difference?

“There was probably less rustling.” He laughs, suddenly and loudly.

When Depeche Mode began recording Songs Of Faith And Devotion in February of 1992, Dave Gahan had been living with Teresa in L.A. for most of the previous year. But a lot of 1991 was taken up with the divorce from Joanne. If that wasn’t enough, he heard one day that his estranged father had died. He had hardly known his father, but it seemed that connections with his past were disappearing. “In the space of six months,” he recalls, “everything just piled on top of me.”

Last edited:

The Dave Gahan who flew to the modern, glass-fronted villa in Madrid that Depeche Mode had rented to live and record the album in was surprisingly different from the one they had known. The first session was a disaster. Having soaked up the West Coast rock ambience, Dave was keen on making a more raucous, aggressive record. There were arguments. “A lot of the time,” Dave confesses, “it was hard for them to even want to be in the same room as me.”

In April, a month before his thirtieth birthday, Gahan flew back to the U.S. and married Teresa at the Graceland Wedding Chapel in Las Vegas, witnessed by a large but unconvincing late-period Elvis lookalike supplied by the chapel. None of the rest of the band were present. [2] Dave wore a dark see-through shirt that showed off the tattoos that he’d recently had done on his chest: above his right nipple a large, dark, hippie “Om” symbol (“which represents every sound in the universe”) to go with the one that Teresa already had on her chest, and on the other side a large, dark phoenix to symbolise his own spiritual rebirth.

In the Depeche Mode documentary, 101, you can see Teresa, young-looking, in denim, pink lipstick, and blonde hair. By the wedding she was a thin-cheeked brunette vamp.

Your wife’s in 101, isn’t she? I ask.

“Yeah,” he says, misunderstanding what I’d said. “So is Teresa.”

No, I say, that’s what I meant: Teresa’s in the video.

Gahan catches himself, then grins. “She’d rather you didn’t mention that.”

But he’s right. Joanne’s there, too, looking like the rock’n’roll wife, flying out for the big end-of-tour gig, sitting backstage smiling, a little out of place.

“I hope,” Gahan tells me, “that Joanne falls in love and she can be as happy in that area of life as I am, because then she’ll know and understand why I had to do it. It was for very selfish reasons.”

I find myself making a platitudinous thirty-something comment about how sometimes you need to be selfish.

“I have a son as well,” he says. Jack, aged five, lives with his ex-wife. “It’s a heartache. I want to influence him, but I’m not there, so get real, you know? I don’t want him to grow up with the same feelings I had when my stepfather died, wondering what was going on. I want Jack to know that he has a father.”

When Gahan talks about his past he talks like he’s crawled out of some big dark hole. Were drinking and drugs part of it?

He takes a breath and says, hesitantly, “Drinking? Yeah. When you’re in a band, you’re in a gang. And when you go out, you rule. You hit a town and take over. You can go to any club. Whatever you need you can get. And you do.”

A couple of minutes later I ask him the question a little more directly. Did you have a drug dependency?

“Mmmm,” Gahan pauses. After a second he says, “Not really.” Then more emphatically, “No, no. I was drinking way too much, but then I think most people do when they get to that age. A little drink turned into a big one.”

The next day on my way to meet the band I am asked discreetly and politely by Depeche Mode’s publicist not to ask any more questions about drugs.

The second day in the studio with Depeche Mode, the group are acting warily. When I walk into the studio where Flood, Gore and Gahan are working, the conversation dries. Gahan reaches for a bottle of Aqua Libra and takes a swig out of it.

Depeche Mode get anxious about exposing themselves. The first time I met them was in 1985, at one of those turn-up-to-be-seen parties full of tanned radio DJs. Depeche Mode were sitting in the corner unhappily getting drunk. When I said I was surprised to see them there, Andy and Martin told me forlornly that their record plugger told then it would be a good idea. [3]

In 1988 they hired D. A. Pennebaker to shoot 101, a film that covered their U.S. tour to its final date at the Rose Bowl. Pennebaker’s most famous film, Don’t Look Back, is full of candid footage that contributed hugely to the image of Bob Dylan as a mordant, messianic wordsmith. 101 is notable for absence of offstage footage. The longest sequence is one in which Alan Wilder explains how his keyboard works.

Depeche Mode has always been a small, self-managed, independent operation. If you look at tour credits over the years, you’ll see the same names. It took Flood a great deal of persuasion to get the band to let him use an orchestra and backing singers on the album. Depeche Mode treat outsiders with suspicion.

The prospect of working with a journalist in the studio a second day is making them twitchy. Gahan has one of his last vocals to do for “Rush”, and he’s acting nervous. The atmosphere lightens only momentarily when Flood tells people to watch his calls when he’s out of the room because he’s expecting a call from The Edge. “Name-dropper,” Gahan taunts.

Before he disappears into the recording booth, he takes me out of the room and tells me that last night, lying in bed, he began to wonder if he’d said too much. He spoke to Teresa about it; she said as long as he was honest, she was sure it was O.K. “A lot of what we were talking about last night,” he says. “… I mean, to be honest, I’d had a couple of beers. Sometimes I feel maybe a bit foolish.”

The recording booth is blacked out, illuminated only by a couple of candles. I can’t see Gahan in there. He’s trying to get the timing of a line right. “When I come up,” his voice fills the studio control room, “I rush for you.” But his voice is cracking, and he flubs it a couple of times.

“Perhaps,” whispers the publicist, “we should think about heading off.”

I shake hands with the group and wave at an invisible Gahan through the glass but I can’t see whether he can see me or not.

As I’m walking down the stairs outside into fresh air, a voice, amplified with reverb, comes booming at me from the control room.

“Be kind,” David Gahan calls after me.

In April, a month before his thirtieth birthday, Gahan flew back to the U.S. and married Teresa at the Graceland Wedding Chapel in Las Vegas, witnessed by a large but unconvincing late-period Elvis lookalike supplied by the chapel. None of the rest of the band were present. [2] Dave wore a dark see-through shirt that showed off the tattoos that he’d recently had done on his chest: above his right nipple a large, dark, hippie “Om” symbol (“which represents every sound in the universe”) to go with the one that Teresa already had on her chest, and on the other side a large, dark phoenix to symbolise his own spiritual rebirth.

In the Depeche Mode documentary, 101, you can see Teresa, young-looking, in denim, pink lipstick, and blonde hair. By the wedding she was a thin-cheeked brunette vamp.

Your wife’s in 101, isn’t she? I ask.

“Yeah,” he says, misunderstanding what I’d said. “So is Teresa.”

No, I say, that’s what I meant: Teresa’s in the video.

Gahan catches himself, then grins. “She’d rather you didn’t mention that.”

But he’s right. Joanne’s there, too, looking like the rock’n’roll wife, flying out for the big end-of-tour gig, sitting backstage smiling, a little out of place.

“I hope,” Gahan tells me, “that Joanne falls in love and she can be as happy in that area of life as I am, because then she’ll know and understand why I had to do it. It was for very selfish reasons.”

I find myself making a platitudinous thirty-something comment about how sometimes you need to be selfish.

“I have a son as well,” he says. Jack, aged five, lives with his ex-wife. “It’s a heartache. I want to influence him, but I’m not there, so get real, you know? I don’t want him to grow up with the same feelings I had when my stepfather died, wondering what was going on. I want Jack to know that he has a father.”

When Gahan talks about his past he talks like he’s crawled out of some big dark hole. Were drinking and drugs part of it?

He takes a breath and says, hesitantly, “Drinking? Yeah. When you’re in a band, you’re in a gang. And when you go out, you rule. You hit a town and take over. You can go to any club. Whatever you need you can get. And you do.”

A couple of minutes later I ask him the question a little more directly. Did you have a drug dependency?

“Mmmm,” Gahan pauses. After a second he says, “Not really.” Then more emphatically, “No, no. I was drinking way too much, but then I think most people do when they get to that age. A little drink turned into a big one.”

The next day on my way to meet the band I am asked discreetly and politely by Depeche Mode’s publicist not to ask any more questions about drugs.

The second day in the studio with Depeche Mode, the group are acting warily. When I walk into the studio where Flood, Gore and Gahan are working, the conversation dries. Gahan reaches for a bottle of Aqua Libra and takes a swig out of it.

Depeche Mode get anxious about exposing themselves. The first time I met them was in 1985, at one of those turn-up-to-be-seen parties full of tanned radio DJs. Depeche Mode were sitting in the corner unhappily getting drunk. When I said I was surprised to see them there, Andy and Martin told me forlornly that their record plugger told then it would be a good idea. [3]

In 1988 they hired D. A. Pennebaker to shoot 101, a film that covered their U.S. tour to its final date at the Rose Bowl. Pennebaker’s most famous film, Don’t Look Back, is full of candid footage that contributed hugely to the image of Bob Dylan as a mordant, messianic wordsmith. 101 is notable for absence of offstage footage. The longest sequence is one in which Alan Wilder explains how his keyboard works.

Depeche Mode has always been a small, self-managed, independent operation. If you look at tour credits over the years, you’ll see the same names. It took Flood a great deal of persuasion to get the band to let him use an orchestra and backing singers on the album. Depeche Mode treat outsiders with suspicion.

The prospect of working with a journalist in the studio a second day is making them twitchy. Gahan has one of his last vocals to do for “Rush”, and he’s acting nervous. The atmosphere lightens only momentarily when Flood tells people to watch his calls when he’s out of the room because he’s expecting a call from The Edge. “Name-dropper,” Gahan taunts.

Before he disappears into the recording booth, he takes me out of the room and tells me that last night, lying in bed, he began to wonder if he’d said too much. He spoke to Teresa about it; she said as long as he was honest, she was sure it was O.K. “A lot of what we were talking about last night,” he says. “… I mean, to be honest, I’d had a couple of beers. Sometimes I feel maybe a bit foolish.”

The recording booth is blacked out, illuminated only by a couple of candles. I can’t see Gahan in there. He’s trying to get the timing of a line right. “When I come up,” his voice fills the studio control room, “I rush for you.” But his voice is cracking, and he flubs it a couple of times.

“Perhaps,” whispers the publicist, “we should think about heading off.”

I shake hands with the group and wave at an invisible Gahan through the glass but I can’t see whether he can see me or not.

As I’m walking down the stairs outside into fresh air, a voice, amplified with reverb, comes booming at me from the control room.

“Be kind,” David Gahan calls after me.

[2] - You can see a picture taken at the wedding here, in Bong 17.

[3] - This is the article already referred to - Zig Zag, August 1985.

In the Mode from Magazine Details. April 1993. Written by William Shaw.

Transcribed by Francisco J. Rodríguez.

>From Magazine Details April 1993

Exclusive Depeche Mode

David Gagan Comes Clean by William Shaw

Transcribe by Franciso J. Rodr?guez

IN THE MODE

Depeche Mode are (1) techno pioneers. (2) synthpop pervs, (3) The Second Coming]

During the making of their new LP, Songs of Faith and Devotion, the band lived out the record's themes of darkness and salvation. William Shaw joined the fun.

Dave Gahan looks me over suspiciously, '?I remember you reviewed one of our singles once,'? he says. 'Can't remember if it was good or bad.' He escorts me into a playback room in London'?s Olympic Studios to listen to seven of the tracks Depeche Mode have spentten arduous months making. Dave tells me to sit between the two enormous speakers on the mixing desk, because that'?s the best place to hear it. He doesn't sit next to me; he's heard it all a thousand times before. So I sit there alone and listen, scribbling notes, wondering what he would like me to say. Gahan is a bundle of nervous intensity, noddling his head in time to the music, scrutinizing en for a reaction.

When it'?s over he asks me what I think of it.

I enthuse. I seem to pass the test. Gahan stands up, clutching a can of Budweiser, and says, '?I was watching you and I could tell you got something. '? He starts talking abouit this album, how it'?s the best thing he'?s been involved with, how it'?s not been easy, about how it'?s partly all wrapped up in stuff he'?s been going through and partly to do with the way the world is at the moment. '?It'?s something that'?s needed,'? he tells me, '?It'?s a positive thing.'?

For Dave Gahan, this album is therapy. The last few years have been strange and painful.

The album is pertty much finished. This is the third and final recording session. They started 1992 in Madrid, moved to Hamburg, and now they'?re back in London. Today they'?ve been finiching a rhythm track for '?Rush,'? a loose poundig of sequencers and guitars that'?s million miles from the clean electronic music they started out with thirteen years ago. Alan Wilder is concentrating on a screen full of numbers, Wearing a black woolen hat pulled down to his ears, Martin Gore sits in front of a mixing desk with Flood, the producer who worked with the group on their 1990 LP, Violator.

Occasionally Andy Fletcher, who doesn'?t have much to do with the music at this stage, sticks his head in to see how it'?s going. Two weeks more and it'?s all over.

Depeche Mode know that after a very long while thay are teetering on the brink of something very large indeed. Each time they release a record they sell more, moving on from being the odd English cult artists who went Top 20 in the U.S. in 1984 with '?People Are People'? to felleing stadiums and selling six million copies of Violator.

Dave Gahan has changed since Violator. Visually he is unrecognizable. That, originally, was the point. After the tour he needed a break. He moved to Los Angeles and grew his hair to his shoulders and made the goatee he'?s flirted wiht in the past a more permanent fixture. He began to prefer people calling him David, though no one really does. He started listening to Jane'?s Addiction, Soundgarden, and Neil Young. '? Now I'?m just a total and absolute Neilhead.'?

The biggest difference is in the way he acts. Before, he shared his other band members'? diffidence; now, he'?s self-possessed and hyperactive with enthusiasm. I'?m so amazed at the transformation that i tell him so. He lowers his voice and says, '?Every single aspecto of my life has changed in the las couple of years. Everyting. I'?d like to think that I'?m a much better person than i was before. '? He looks me in the eye. '?I'?ve been through a los of stuff, William'?.

A lot of things have happened to Dave Gahan. He comes from Basildon, a postwar town twenty miles northeast of London, significantly off the tourist maps and, in the late '?70s, brim full of bored teenagers scuffling on the streets. Dave Gahan was one of them. His dad left home when he was about six months old, returning only briefly for a few years when Dave was seven, after his stepfather died. In Gahan'?s early teenage years he got into what he describes as '?a dodgy phase'? stealing motorbikes; it was just what boys did in that part of Basildon. He was saved from getting into anything worse when he met Vince Clark, Andy Fletcher, and Martin Gore, From the other, nicer side of town. The three of them were in a group called Composition of Sound and Played synthesizers. Painfully aware of a lack of charisma, they knew they needed a frontman. One day they turned up to rehearse in the local scout hall and heard Gahan running through a version of David Bowie'?s '?Hero'? with another band.

Depeche Mode'?s fist champion, producer Daniel Miller, used to be a film editor. he had a minor late '?70s hit with '?T.V.O.D.,'? a primitive electronic single, so he formed his own label, Mute, and started releasing synthpop cover versions under the banner of Silicon Teens. When he came across four real teenagers playing sweetly harmonized electronic music in a pub in east London, it was too good to be true.

It was 1981, the year of the British New Romantic Movement. In those days Dave Gahan wore baggy suits and cute bow ties. A neatly coiffeured New Romantic fringe drooped in front of his eyes and a stud shone form his pierced nose. Depeche Mode had a couple of hits, became pinups, and seemed to be nothing more than microprocessed bubblegum. But by the end of the year Vince Clarke, the band'?s songwriter, had left (to form Yaz and, Later Erasure), and Marting Took over. Gore began spending time in Berlin and, Though he downplays it, was inspired by industrial noisemakers like Einsturzende Neubauten. Subsequently, Depeche Mode fashioned a harder electronic backdrop for Gore;s increasingly sophisticated songs about teenage suicide and twisted romanticism.

By the middle of the decade, Gahan too had undergone a transformation. He was no longer the slight teenager who on the group'?s first tour had stood awkwardly onstage, waiting for somebody to cue up the backing tapes. Now he had a new stage routine, full of pirouettes, kicks, mike stand swinging, and sweat. Audiences began to swoon for his wiggling, leather clad bottom.

At the time, Dave was going out with a Basildon girl named Joanne. For a while she ran the Mode Fan Club. In 1985 they maried. In 1987 they had a son, Jack. In 1991 they started getting devorced.

Transcribed by Francisco J. Rodríguez.

>From Magazine Details April 1993

Exclusive Depeche Mode

David Gagan Comes Clean by William Shaw

Transcribe by Franciso J. Rodr?guez

IN THE MODE

Depeche Mode are (1) techno pioneers. (2) synthpop pervs, (3) The Second Coming]

During the making of their new LP, Songs of Faith and Devotion, the band lived out the record's themes of darkness and salvation. William Shaw joined the fun.

Dave Gahan looks me over suspiciously, '?I remember you reviewed one of our singles once,'? he says. 'Can't remember if it was good or bad.' He escorts me into a playback room in London'?s Olympic Studios to listen to seven of the tracks Depeche Mode have spentten arduous months making. Dave tells me to sit between the two enormous speakers on the mixing desk, because that'?s the best place to hear it. He doesn't sit next to me; he's heard it all a thousand times before. So I sit there alone and listen, scribbling notes, wondering what he would like me to say. Gahan is a bundle of nervous intensity, noddling his head in time to the music, scrutinizing en for a reaction.

When it'?s over he asks me what I think of it.

I enthuse. I seem to pass the test. Gahan stands up, clutching a can of Budweiser, and says, '?I was watching you and I could tell you got something. '? He starts talking abouit this album, how it'?s the best thing he'?s been involved with, how it'?s not been easy, about how it'?s partly all wrapped up in stuff he'?s been going through and partly to do with the way the world is at the moment. '?It'?s something that'?s needed,'? he tells me, '?It'?s a positive thing.'?

For Dave Gahan, this album is therapy. The last few years have been strange and painful.

The album is pertty much finished. This is the third and final recording session. They started 1992 in Madrid, moved to Hamburg, and now they'?re back in London. Today they'?ve been finiching a rhythm track for '?Rush,'? a loose poundig of sequencers and guitars that'?s million miles from the clean electronic music they started out with thirteen years ago. Alan Wilder is concentrating on a screen full of numbers, Wearing a black woolen hat pulled down to his ears, Martin Gore sits in front of a mixing desk with Flood, the producer who worked with the group on their 1990 LP, Violator.

Occasionally Andy Fletcher, who doesn'?t have much to do with the music at this stage, sticks his head in to see how it'?s going. Two weeks more and it'?s all over.

Depeche Mode know that after a very long while thay are teetering on the brink of something very large indeed. Each time they release a record they sell more, moving on from being the odd English cult artists who went Top 20 in the U.S. in 1984 with '?People Are People'? to felleing stadiums and selling six million copies of Violator.

Dave Gahan has changed since Violator. Visually he is unrecognizable. That, originally, was the point. After the tour he needed a break. He moved to Los Angeles and grew his hair to his shoulders and made the goatee he'?s flirted wiht in the past a more permanent fixture. He began to prefer people calling him David, though no one really does. He started listening to Jane'?s Addiction, Soundgarden, and Neil Young. '? Now I'?m just a total and absolute Neilhead.'?

The biggest difference is in the way he acts. Before, he shared his other band members'? diffidence; now, he'?s self-possessed and hyperactive with enthusiasm. I'?m so amazed at the transformation that i tell him so. He lowers his voice and says, '?Every single aspecto of my life has changed in the las couple of years. Everyting. I'?d like to think that I'?m a much better person than i was before. '? He looks me in the eye. '?I'?ve been through a los of stuff, William'?.

A lot of things have happened to Dave Gahan. He comes from Basildon, a postwar town twenty miles northeast of London, significantly off the tourist maps and, in the late '?70s, brim full of bored teenagers scuffling on the streets. Dave Gahan was one of them. His dad left home when he was about six months old, returning only briefly for a few years when Dave was seven, after his stepfather died. In Gahan'?s early teenage years he got into what he describes as '?a dodgy phase'? stealing motorbikes; it was just what boys did in that part of Basildon. He was saved from getting into anything worse when he met Vince Clark, Andy Fletcher, and Martin Gore, From the other, nicer side of town. The three of them were in a group called Composition of Sound and Played synthesizers. Painfully aware of a lack of charisma, they knew they needed a frontman. One day they turned up to rehearse in the local scout hall and heard Gahan running through a version of David Bowie'?s '?Hero'? with another band.

Depeche Mode'?s fist champion, producer Daniel Miller, used to be a film editor. he had a minor late '?70s hit with '?T.V.O.D.,'? a primitive electronic single, so he formed his own label, Mute, and started releasing synthpop cover versions under the banner of Silicon Teens. When he came across four real teenagers playing sweetly harmonized electronic music in a pub in east London, it was too good to be true.

It was 1981, the year of the British New Romantic Movement. In those days Dave Gahan wore baggy suits and cute bow ties. A neatly coiffeured New Romantic fringe drooped in front of his eyes and a stud shone form his pierced nose. Depeche Mode had a couple of hits, became pinups, and seemed to be nothing more than microprocessed bubblegum. But by the end of the year Vince Clarke, the band'?s songwriter, had left (to form Yaz and, Later Erasure), and Marting Took over. Gore began spending time in Berlin and, Though he downplays it, was inspired by industrial noisemakers like Einsturzende Neubauten. Subsequently, Depeche Mode fashioned a harder electronic backdrop for Gore;s increasingly sophisticated songs about teenage suicide and twisted romanticism.

By the middle of the decade, Gahan too had undergone a transformation. He was no longer the slight teenager who on the group'?s first tour had stood awkwardly onstage, waiting for somebody to cue up the backing tapes. Now he had a new stage routine, full of pirouettes, kicks, mike stand swinging, and sweat. Audiences began to swoon for his wiggling, leather clad bottom.

At the time, Dave was going out with a Basildon girl named Joanne. For a while she ran the Mode Fan Club. In 1985 they maried. In 1987 they had a son, Jack. In 1991 they started getting devorced.

Dave sits on the sofa in the studio. He wants to talk about the new album, about the divorce and his new marriage, about why everything is better now. '?You start out with all the right intentions when you'?ra in a band, and it'?s not that you lose those ideals - you just get wrapped up in the band. I thought it was time to readdress my life because there were aspects of it that were just so wrong and i had to change'?.

By the Violator tour, Gahan was losing control. His personal life was a mess. A little bit of partying is fairly normal Depeche behavior, but Gahan was pilling out all the stops. The rest of the band were becoming worried. '?I think he just felt that performing was the only thing he could do right, '?Andy Fletcher remembers. '?He was very emotional with all of us. I personally tended to steer clear of him.'?

For years Dave'?s mariage was falling into the familiar boy marries girl becomes rock-god trap. He was sleeping around on the road. A lot. He felt awful about if, but couldn'?t make himself stop. '?You make yourself blind and you go out there. It'?s great to meet lots of different girls and have fun, but then you realize what a chit you are and how you'?re destroying other people'?s lives-or life- wiht it.'?

Did you really feel guilty about it?

He groans and smiles self-consciously. '?absolutely, and it had been building up for years. I think. . . '? he puses, '?Well, I know, well. . . I think pretty much I know. . . that my wife, my previous wife was completely faithful to me. And I'?d go back to her and. . . not lie, because Joanne wouldn'?t even ask me things.'?

Presumably she suspected.

'?I'?m sure shi did. She wasn'?t stupid.'?

Things came to a head in 1990 when Gahan fell in love, teresa Conroy was a publicist who'?d worked for producer Rick Rubin. In 1988 she worked on Depeche Mode'?s Music for the Mases tour. In those days she had bleached-blonde hair and wore punky clothes. She traveled with the band, setting up interviews and ticket giveaways on local radio stations. After the tour, Gahan headed back to Joanne and Jack in England. But during '?89, when he was in Milan recording Violator, he'?d call Teresa up, ofthen drunk, and talk about what he was doing.

They met again at rekersals for the Violator tour. Gahan realized he had fallen in love with Teresa, and it was like being smashed on the head with a hammer. '?You look at yourself in the mirror one morning and suddenly everything'?s very, very different ant the whole perspective has suddenly changed. Last night wasn'?t just '? I wanted to get laid'? - I didn'?t want to be that person anymore. Teresa brought out some emotions in me that I hadn'?t discovered, like love,'? he says, tochingly.

I remind him he once said that every though he sang about love, he didn'?t

fall in love himself.

He thinks for a bit and then says, '?Well, I think I was just denying my true feelings a lot of the time, having to lie my way through a lot of my life with people I was supposed to respect and love and care for. So I blew that completely.'?

The new Lp is Depeche Mode'?s Joshua Tree, the moment when a cult band transforms itself with a loud declaration of self confidence. There are still moments of minor key introversion, like in the sinister love song '?In Your Room,'? but much of it is rich, loud, bluesy, electronic roch. Dave Gahan'?s increasing influence on the group is clear in the euphoric stadium roch of '?Ruch,'? and there are spirituals like '?Get Right With Me,'? Complete with gospel choir, and '?Higher Love,'? which Fletch appositely describes as '?our Tear for Fears number.'? Plus the low - key Martin Gore moment, where he steps out of the shadows and sings the ballad '?One Caress'? to a ringing string arrangement.

The new album is called Songs of Faid and Devotion. It'?s not the first time Martin has revelled in his love for religious imagery, but the record might also be about the last few years of Deve Gahan'?s life. Gore denies that he actully wrote the album for Gahan'?s situation, but its themes of love and salvation fit pretty well. In 1991 Martin Became a father. Since then, he says, his songs are more '?uplifting and positive.'? In the words of the ever pragmatic Andy Fletcher, the new songs are '?a bit more emotional and les pervy.'?

Seven years ago, I sat next to Fletcher at a meal. He was fretting about the future. '?When Martin stops writing songs,'? he said, '?it'?s all over.'? It was as if he were worried that because Gore'?s songwriting talent had emerged so micaculously, apparently from nowher, that it might suddenly disapeear. Martin was sitting across the table, drinking. Someone from his record company leaned over and warned that any minute now Martin was going to start taking his clothes off. '?He does that when he'?s drunk,'? she insisted.

Martin Gore is a strange, elusive man. '?I was probably a wierd child,'? he says, and you perch on the edge of your seat to hear just how weird he was. Yhen he says, '?Because I quite liked school and stuff.'?

Marin Gore is that sort of weird.

He came from a working-class background, the other side of Basildon from Dave Gahan. At Nicholas School, a large, grim public school. He was a likable bou who like todo the right thing. Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher went to the same school, ad did Alison Moyet, who later formed Yaz with Clark, and Perry Bamonte, keyboard player with the Cure. Bamonte remembers Gore as '?very, very introverted.'? One typically Gore-esque incident occurred five minutes before the bell rang in math. Gore turned each time he asked and looked blankly at him. '?He just flatly refused, '? says Bamonte, '?It wasn'?t the done thing.'?

By the Violator tour, Gahan was losing control. His personal life was a mess. A little bit of partying is fairly normal Depeche behavior, but Gahan was pilling out all the stops. The rest of the band were becoming worried. '?I think he just felt that performing was the only thing he could do right, '?Andy Fletcher remembers. '?He was very emotional with all of us. I personally tended to steer clear of him.'?

For years Dave'?s mariage was falling into the familiar boy marries girl becomes rock-god trap. He was sleeping around on the road. A lot. He felt awful about if, but couldn'?t make himself stop. '?You make yourself blind and you go out there. It'?s great to meet lots of different girls and have fun, but then you realize what a chit you are and how you'?re destroying other people'?s lives-or life- wiht it.'?

Did you really feel guilty about it?

He groans and smiles self-consciously. '?absolutely, and it had been building up for years. I think. . . '? he puses, '?Well, I know, well. . . I think pretty much I know. . . that my wife, my previous wife was completely faithful to me. And I'?d go back to her and. . . not lie, because Joanne wouldn'?t even ask me things.'?

Presumably she suspected.

'?I'?m sure shi did. She wasn'?t stupid.'?

Things came to a head in 1990 when Gahan fell in love, teresa Conroy was a publicist who'?d worked for producer Rick Rubin. In 1988 she worked on Depeche Mode'?s Music for the Mases tour. In those days she had bleached-blonde hair and wore punky clothes. She traveled with the band, setting up interviews and ticket giveaways on local radio stations. After the tour, Gahan headed back to Joanne and Jack in England. But during '?89, when he was in Milan recording Violator, he'?d call Teresa up, ofthen drunk, and talk about what he was doing.

They met again at rekersals for the Violator tour. Gahan realized he had fallen in love with Teresa, and it was like being smashed on the head with a hammer. '?You look at yourself in the mirror one morning and suddenly everything'?s very, very different ant the whole perspective has suddenly changed. Last night wasn'?t just '? I wanted to get laid'? - I didn'?t want to be that person anymore. Teresa brought out some emotions in me that I hadn'?t discovered, like love,'? he says, tochingly.

I remind him he once said that every though he sang about love, he didn'?t

fall in love himself.

He thinks for a bit and then says, '?Well, I think I was just denying my true feelings a lot of the time, having to lie my way through a lot of my life with people I was supposed to respect and love and care for. So I blew that completely.'?

The new Lp is Depeche Mode'?s Joshua Tree, the moment when a cult band transforms itself with a loud declaration of self confidence. There are still moments of minor key introversion, like in the sinister love song '?In Your Room,'? but much of it is rich, loud, bluesy, electronic roch. Dave Gahan'?s increasing influence on the group is clear in the euphoric stadium roch of '?Ruch,'? and there are spirituals like '?Get Right With Me,'? Complete with gospel choir, and '?Higher Love,'? which Fletch appositely describes as '?our Tear for Fears number.'? Plus the low - key Martin Gore moment, where he steps out of the shadows and sings the ballad '?One Caress'? to a ringing string arrangement.

The new album is called Songs of Faid and Devotion. It'?s not the first time Martin has revelled in his love for religious imagery, but the record might also be about the last few years of Deve Gahan'?s life. Gore denies that he actully wrote the album for Gahan'?s situation, but its themes of love and salvation fit pretty well. In 1991 Martin Became a father. Since then, he says, his songs are more '?uplifting and positive.'? In the words of the ever pragmatic Andy Fletcher, the new songs are '?a bit more emotional and les pervy.'?

Seven years ago, I sat next to Fletcher at a meal. He was fretting about the future. '?When Martin stops writing songs,'? he said, '?it'?s all over.'? It was as if he were worried that because Gore'?s songwriting talent had emerged so micaculously, apparently from nowher, that it might suddenly disapeear. Martin was sitting across the table, drinking. Someone from his record company leaned over and warned that any minute now Martin was going to start taking his clothes off. '?He does that when he'?s drunk,'? she insisted.

Martin Gore is a strange, elusive man. '?I was probably a wierd child,'? he says, and you perch on the edge of your seat to hear just how weird he was. Yhen he says, '?Because I quite liked school and stuff.'?

Marin Gore is that sort of weird.

He came from a working-class background, the other side of Basildon from Dave Gahan. At Nicholas School, a large, grim public school. He was a likable bou who like todo the right thing. Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher went to the same school, ad did Alison Moyet, who later formed Yaz with Clark, and Perry Bamonte, keyboard player with the Cure. Bamonte remembers Gore as '?very, very introverted.'? One typically Gore-esque incident occurred five minutes before the bell rang in math. Gore turned each time he asked and looked blankly at him. '?He just flatly refused, '? says Bamonte, '?It wasn'?t the done thing.'?

At thirteen, he was given an acoustic guitar, and he played it to death. He enjoyed being alone. '? I didn'?t use to go out very much between about sixteen and eighteem; I actually gave up drink for two years, '?when DM were having thier first U.K. success with Vince Clarke'?s bright electropop songs, Marting was still Mr. Ordinary working diligently at a local bank and going to church at the local Mechodist chapel. It was only when their songwriter Clarke quit the band after their first album that Gore was thrust into the role of Depeche Mode'?s songwriter and suddenly started to turn out the strangely subversive pop songs that have become the backbone of the group.

Andy. His closest friend in the band, admits he doesn'?t really see the connection between Martin and his songs. '?He'?s a realy normal person. He likes to drink, he likes playing football, he likes really normal things, yet when he gets into a creating mode he seems to come upwith these wonderful songs which make This hero in some people'?s eyes. It does amaze me; there'?s nothing in his background to illustrate why this should happen.'?

Gahan, more naturally extroverted, once put forward the theory that a lot of it came from the fact that Gore had missed out on his teens. When Gahan was out stealing motorbikes, Gore was up in his bedroom strumming Simon and Garfunkel songs.

The best Gore songs are about relationchips. His words and melodies can be deceptively simple, but they celebrate the abnormality of love, treading a line between darkness and a camp humor. '?Strangelove'? and '?Enjoy the Silence'? revel in a claustrophobic subservience to love; '?Little 15'? and '?A Question of Time'? look at innocence on the edge of corruption; '?Master and Sevant'? and '?Behind the Wheel'? deal with the imagery of submission.

Gore is horrified by the ideas people get about him. He Laughs nervously. '?I should imagine from reading the lyrics,'? he ventures, '?they'?d think I was dark and moody with quite a perverted sense of things.'? He speaks with the slightest of lisps.

Gore'?s least favorite subject is himself. He looks pained when he'?s asked to talk about it. He sighs and shakes his head. If you ask him where he gets all these sexual power images, he comes to a shuddering, embarrassed halt and puts on his '?next question'? face. His least favorite question of all time is whether '?Master and Servant'? has an autobiographical element. He blurts, '?That was used metaphorically!'?

But don'?t songs like that make people wonder if you'?re interested in that sort of sexuality?

'?It comes up so often in songs that I must be,'? Martin answers flippantly.

Do you practice it?

'?What do you mean by '?that sort of sexuality'?? Where you put yourself in

dominant or submissive roles?'?

Yes.

Martin answers briefly , '?I think that'?s personal stuff, really.'?

Are you interested in pornography?

He exhales. '?Yeah.'? Pause. '?If it'?s well done. It always amazes me that so much pornography is done badly. If it'?s done well...'? He trails off. '? You have to choose your words carefully here, you'?re always treading on dodgy ground.'?

--

In the mid-80s, fetish clubs became fashionable in London, "Iused to go," Gore acknowledges. "Ido like the imagery. I found that the atmosphere in those clubs was very friendly. I'm sure I did get some ideas from going to those kinds of places." Around that time, much to the diwquiet of Gahan, Gore started wearing black nail polish, lipstick, pearl and rhinestone necklaces, and black leather minishkirts onstage.

When was the first time you wore one?

Martin scowls.

You hate that question deeply, Isay.

"That's because it gets brought up in every single interview."

Do you like the idea of androgyny?

"I think so. Maybe it's to do with my dislike of normality. I've always

thought a macho image really boring."

Does that lead to speculation that you're gay?

"That is probably more universal, I think a lot of people think that I'm gay, whichi doesn't offend me or worry me in the slightet. People can think what they like."

Downstairs in the studio canteen, the group is eating lasagna and talking endof-album business. Alan Wilder is making tha case for leading off the LP with "I Feel You." Alan is the one who learned classical keyboards and played with go-nowhere groups like Daphne and the Tenderspots and the Hitmen before he answered the ad in the paper after Vince Clarke had left: "Name band, Synthesizer, must be under twenty one." He got the spot even though he was twenty two. Wilder toured in '82 and became an official member the following hear. The oldesr of the group at thity three, he sees himself as a pure musician. He writes symphonies in his sleep, though he can never quite remember them in the morning, and regards tourig, promotion, and videos as a distraction from the studio.In the beginning he contributed a few B-side songs to Depeche Mode singles, but these days he leaves his writing to his side prohect, Recoil; he has produced an LP for Nitzerebb and will soon work with Curve.

Fletch appears, clutching a wad of CD packaging samples. He is the odd-job man, the group ambassador to the music industry, a regular reader of billboard and the Economist. Infinitely sensible, he worked as an insurace clerk until he was sure that Depeche Mode were a going concern. As the years pass by, the less he's involved in music, the more he gets the management tasks. This hardly bothers him. "Itake no interest in the making of the music," Fletcher says.

He Drops the CD samples on the table. "I don't buy CD.s . You have to tell me."

Alan turns to me and says, by the way of explanation, "He doesn't listen to music."

Fletch smiles and nods. He has a house by the thames where he can fish in the river from his own garden and owns a stake in a restaurant. Like Gore, he had a daughter this year, In Nivember he got married to his girlfriend, Grainne.

Fletch tells the others he has budget proposals for the upcoming videos, "You got Anton's?" ask Dave.

Over the last few years, photographer Anton Corbijn, who like coproducer Flood, works closely with U2, has joined the group's inner circle. He provides brilliantly moody images that allow the group to thrive in relative anonymity on video.

"How much?" asks Gahan.

"A hundred thousand," says fletch.

"Pounds or dollars?"

"Pounds."

"Fucking hell," Gahan exclaims.

"And it's only black and white," Fletch explains. Big Laugh.

Andy. His closest friend in the band, admits he doesn'?t really see the connection between Martin and his songs. '?He'?s a realy normal person. He likes to drink, he likes playing football, he likes really normal things, yet when he gets into a creating mode he seems to come upwith these wonderful songs which make This hero in some people'?s eyes. It does amaze me; there'?s nothing in his background to illustrate why this should happen.'?

Gahan, more naturally extroverted, once put forward the theory that a lot of it came from the fact that Gore had missed out on his teens. When Gahan was out stealing motorbikes, Gore was up in his bedroom strumming Simon and Garfunkel songs.

The best Gore songs are about relationchips. His words and melodies can be deceptively simple, but they celebrate the abnormality of love, treading a line between darkness and a camp humor. '?Strangelove'? and '?Enjoy the Silence'? revel in a claustrophobic subservience to love; '?Little 15'? and '?A Question of Time'? look at innocence on the edge of corruption; '?Master and Sevant'? and '?Behind the Wheel'? deal with the imagery of submission.

Gore is horrified by the ideas people get about him. He Laughs nervously. '?I should imagine from reading the lyrics,'? he ventures, '?they'?d think I was dark and moody with quite a perverted sense of things.'? He speaks with the slightest of lisps.

Gore'?s least favorite subject is himself. He looks pained when he'?s asked to talk about it. He sighs and shakes his head. If you ask him where he gets all these sexual power images, he comes to a shuddering, embarrassed halt and puts on his '?next question'? face. His least favorite question of all time is whether '?Master and Servant'? has an autobiographical element. He blurts, '?That was used metaphorically!'?

But don'?t songs like that make people wonder if you'?re interested in that sort of sexuality?

'?It comes up so often in songs that I must be,'? Martin answers flippantly.

Do you practice it?

'?What do you mean by '?that sort of sexuality'?? Where you put yourself in

dominant or submissive roles?'?

Yes.

Martin answers briefly , '?I think that'?s personal stuff, really.'?

Are you interested in pornography?

He exhales. '?Yeah.'? Pause. '?If it'?s well done. It always amazes me that so much pornography is done badly. If it'?s done well...'? He trails off. '? You have to choose your words carefully here, you'?re always treading on dodgy ground.'?

--