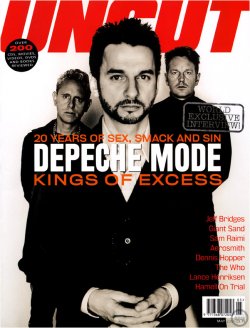

ENJOY THE SILENCE: 20 YEARS OF DEPECHE MODE ALBUMS

SPEAK & SPELL

(May 1981, UK 10)

Clipped, zippy, Fisher Price Europop with helium harmonics, hi-NRG beats and a faintly homoerotic subtext. Mellifluous ditties like 'New Life' and 'Boys Say Go' would sound comically slight by the late Eighties, but history has lent this debut an innocent charm. [3]

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Soft Cell, Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret; Human League, Dare; Ultravox, Rage In Eden.

A BROKEN FRAME

(September 1982, UK 8)

Vince Clarke's upbeat pop sensibilities still linger but Martin Gore's minor chords and lyrical unease prevail. A stark, early Factory Records feel can't salvage these transitional, uncertain songs.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Duran Duran, Rio; Michael Jackson, Thriller.

CONSTRUCTION TIME AGAIN

(August 1983, UK 6) лл

The arrival of the sampler and Gore's new industrial direction combine into an anthology of totalitarian work songs and satirical observations on pop success - most notably 'Everything Counts'. Ungainly tempos still spoil the broth.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Japan, Oil On Canvas; Eurythmics, Sweet Dreams; Einsturzende Neubaten, Kollaps.

SOME GREAT REWARD

(September 1984, UK 5 / US 51) ллл

Tougher beats and metallic textures abound as Gore conceives his first subversive pop masterpiece in 'Master And Servant', 'Blasphemous Rumours' and the achingly personal piano ballad 'Somebody'. Chunky, funky, mid-Eighties production packs a satisfying punch.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Welcome To The Pleasuredome; Madonna, Like A Virgin.

THE SINGLES 81-85

October 1985, UK 6)

From Basildon to Berlin and back again - all the hits and the end of an era in Mode history, as America looms over the horizon.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Blancmange, Believe You Me, The Jesus And Mary Chain, Psychoc Candy; Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, Crush.

BLACK CELEBRATION

(March 1986, UK 4 / US 90)

Impressive use of sampled sound collages, stacked vocal harmonies and symphonic arrangements characterise the Mode's most fully rounded opus to date and US breakthrough. Diversity rules, as Gahan croons like Morrissey and Gore flirts with Brechtian cabaret.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Erasure, Wonderland; The The, Infected; Sigue Sigue Sputnik, Dress For Excess.

MUSIC FOR THE MASSES

(September 1987, UK 10 / US 35)

A commercial setback in Britain but a major leap forward abroad, especially America, this slick collection of brooding pop travelogues finds the Mode on the border between cult act and mainstream phenomenon.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: INXS, Kick; U2, The Joshua Tree; The Jesus And Mary Chain, Darklands.

101

(March 1989, UK 5 / US 45)

A double-live album rounding off a decade of Mode action but these retooled hits add little to their studio blueprints. The monochrome grandeur and sly observation of the film which spawned it is lost in clinical, two-dimensional reproduction.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: U2, Rattle And Hum; New Order, Technique.

VIOLATOR

(March 1990, UK 2 / US 7)

A coming-of-age landmark and major unit shifter, this distillation of pure-pop sensibilities with propulsive motorik rhythms and dry, buoyant, disco-friendly production shows the Mode graduation to consummate albums act rather than great singles band.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Massive Attack, Blue Lines; Pet Shop Boys, Behaviour.

SONGS OF FAITH AND DEVOTION

(March 1993, UK 1 / US 1)

Another fully rounded epic, brimming with transcendent cyber-gospel and ravaged Biblical soundscapes, this widescreen experiment in soulful self-laceration lifts the Mode to a higher musical level and defies the traumatic circumstances surrounding its conception.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Nirvana, In Utero; Nine Inch Nails, The Downward Spiral; PJ Harvey, Rid Of Me.

SONGS OF FAITH AND DEVOTION LIVE

(December 1993, UK 46) лл

Whether unorthodox experiment or festive cash-in, this live set replicated the studio album's running order but added little besides crowd noise, expanded gospel arrangements and Gahan's rock-tastic crowd banter. The tunes remain mighty, but these windy remakes are inessential.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Portishead, Dummy; New Order, Republic.

ULTRA

(April 1997, UK 1 / US 5)

Fashioned from the wreckage of Gahan's drug addiction and Wilder's departure, this strained comeback finds the Mode turning back towards Eurocentric hip-hop for inspiration. Tim Simenon's powerhouse beats and grainy textures please the ear, but the overall mood is weary and fragmented.

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Prodigy, Fat Of The Land; Chemical Brothers, Dig Your Own Hole.

THE SINGLES 86-98

(1999, UK 5 / US 38) ллл

From Basildon to Hell and back again, all the hits plus the closing of another chapter in Mode history - a fine collection but as their LPs have become stronger, DM singles have declined in pure-pop punch. [4]

CONTEMPORARY SOUNDS: Duran Duran, Greatest; Marilyn Manson, Mechanical Animals.

[3] - 'Speak And Spell' was released in November 1981.

[4] - 'The Singles 86-98' was released in September 1998.