- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Many Smack - Free Returns!

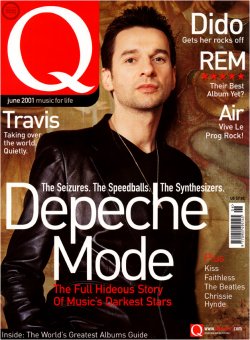

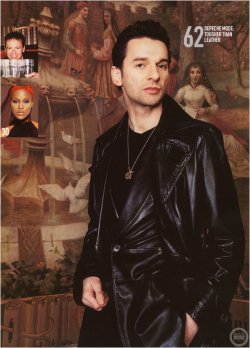

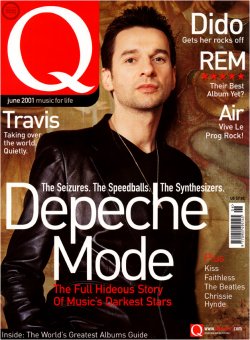

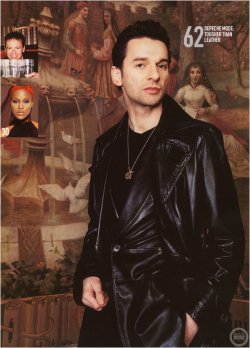

[Q, June 2001. Words: Dorian Lynskey. Pictures: Spiros Politis.]

In summer 1994, the Dave Gahan diet went something like this. After regaining consciousness at some point in the afternoon in a hotel room in America, he would start the day with two glasses of vodka. His throat so ravaged he couldn't speak, the singer would call Jerry, his minder, and communicate by tapping on the phone in code. Then he would get into his limo to the airport, stopping en route to grab a McDonalds, his sole meal of the day. On the plane, it was time for a couple of Valium and a blackout.

When he arrived at the venue, the tour doctors gave him steroids for his throat and painkillers for everything else. "I was a garbage can," he ruefully recalls.

By the time he got on stage, the cocktail of chemicals, spiked with a giant jolt of adrenalin, tended to create an equilibrium so that he'd feel strangely fine, strutting and whooping as if nothing was wrong. Afterwards, though, he would retreat to his hotel room, never once talking to his bandmates, and spend the rest of the night injecting heroin alone. Repeat to fade.

By the end of Depeche Mode's 14-month, 158-date Songs Of Faith And Devotion tour, Dave Gahan weighed just 100 pounds and looked as pale and thin as a chalkmark.

Unbelievably, the next two years were worse still, a gruesome object lesson in Why Heroin Is A Bad Thing. In between abortive spells in rehab, Gahan's life unravelled at terrifying speed - his second wife left him, his first barred him from seeing their young son, Jack, and his house in Los Angeles was ransacked by burglars. He also wound up in hospital emergency rooms so many times that West Hollywood paramedics nicknamed him The Cat. On one occasion, he swallowed wine and valium and slashed his wrists in a suicide attempt. Notoriously, he overdosed on a cocaine and heroin speedball in his room at the Sunset Marquis, suffered a cardiac arrest and was technically dead for two minutes.

Gahan's excesses may have been the most spectacular, but he wasn't the only one in Depeche Mode with problems. During the same tour, fresh-faced songwriter Martin Gore was drinking at least two bottles of wine before every show, convinced that if he tried to perform sober then he would forget how to play. Keyboardist Andy 'Fletch' Fletcher didn't even make it to those final US dates, bailing out in Hawaii after a nervous breakdown. Studio wizard Alan Wilder was hopelessly alienated from his bandmates, and within a year he had left for good.

"You mustn't have this impression that there was one guy having all the problems and causing the whole ship to sink," Andy Fletcher insists, with a strange kind of pride. "There were many holes in the boat."

Behold Depeche Mode, then: the band who never knew when, or how, to stop.

Depeche Mode released their first single, Dreaming of Me, on 20 February 1981, and the fact that they're alive and well 20 years later with their tenth studio album, Exciter, is a small miracle. A British electronic band with the hedonist appetites of American rock pigs, Depeche Mode started partying so hard in the early '80s, and carried on for so long, the wonder is it took them until 1994 to come to the brink of falling apart.

When Dave Gahan's problems became public, they buried the long-running perception of the band as a faintly ludicrous, faux-doomy pop act with a penchant for black leather. Maybe it's their sartorial quirks over the years, or their preference for synthesizers over guitars, but Britain has always had problems taking Depeche Mode seriously.

Happily, they couldn't care less. They're the most enduring and internationally successful British band of their era. Throughout death, drugs, depression and departing members, they have always had an ear for innovation and a good tune, and have never made a rotten album. In America, they are the acme of Anglophile hip - the band that made musings on death, God and S&M seem at home both in stadiums and on dancefloors. Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, Slipknot, Korn, Deftones, DJ Shadow and Detroit techno producers have all doffed caps in their direction.

"I was reading Prozac Nation and I think it's us and The Smiths that she [author Elizabeth Wurtzel] accuses of being 'miserable chic'," guffaws Gore, one of those rare people whose laugh sounds exactly like "ha ha ha". "But we just tried to bring some element of reality into pop music."

[Q, June 2001. Words: Dorian Lynskey. Pictures: Spiros Politis.]

Compelling band biography, with some emphasis on the chaos of the Devotional Tour. However, the author avoids the pitfall of many journalists and avoids dwelling melodramatically on Dave's problems, probably on the (wise) assumption that the details are easily enough had elsewhere. The tone is resolutely upbeat and the photography is stunning. Recommended reading!

" "They defy the laws of gravity," opines Daniel Miller, the Mute label founder who signed and mentored them. "No, they redefine the laws of gravity." "

In summer 1994, the Dave Gahan diet went something like this. After regaining consciousness at some point in the afternoon in a hotel room in America, he would start the day with two glasses of vodka. His throat so ravaged he couldn't speak, the singer would call Jerry, his minder, and communicate by tapping on the phone in code. Then he would get into his limo to the airport, stopping en route to grab a McDonalds, his sole meal of the day. On the plane, it was time for a couple of Valium and a blackout.

When he arrived at the venue, the tour doctors gave him steroids for his throat and painkillers for everything else. "I was a garbage can," he ruefully recalls.

By the time he got on stage, the cocktail of chemicals, spiked with a giant jolt of adrenalin, tended to create an equilibrium so that he'd feel strangely fine, strutting and whooping as if nothing was wrong. Afterwards, though, he would retreat to his hotel room, never once talking to his bandmates, and spend the rest of the night injecting heroin alone. Repeat to fade.

By the end of Depeche Mode's 14-month, 158-date Songs Of Faith And Devotion tour, Dave Gahan weighed just 100 pounds and looked as pale and thin as a chalkmark.

Unbelievably, the next two years were worse still, a gruesome object lesson in Why Heroin Is A Bad Thing. In between abortive spells in rehab, Gahan's life unravelled at terrifying speed - his second wife left him, his first barred him from seeing their young son, Jack, and his house in Los Angeles was ransacked by burglars. He also wound up in hospital emergency rooms so many times that West Hollywood paramedics nicknamed him The Cat. On one occasion, he swallowed wine and valium and slashed his wrists in a suicide attempt. Notoriously, he overdosed on a cocaine and heroin speedball in his room at the Sunset Marquis, suffered a cardiac arrest and was technically dead for two minutes.

Gahan's excesses may have been the most spectacular, but he wasn't the only one in Depeche Mode with problems. During the same tour, fresh-faced songwriter Martin Gore was drinking at least two bottles of wine before every show, convinced that if he tried to perform sober then he would forget how to play. Keyboardist Andy 'Fletch' Fletcher didn't even make it to those final US dates, bailing out in Hawaii after a nervous breakdown. Studio wizard Alan Wilder was hopelessly alienated from his bandmates, and within a year he had left for good.

"You mustn't have this impression that there was one guy having all the problems and causing the whole ship to sink," Andy Fletcher insists, with a strange kind of pride. "There were many holes in the boat."

Behold Depeche Mode, then: the band who never knew when, or how, to stop.

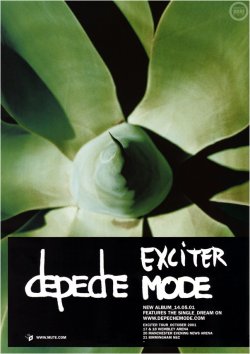

Depeche Mode released their first single, Dreaming of Me, on 20 February 1981, and the fact that they're alive and well 20 years later with their tenth studio album, Exciter, is a small miracle. A British electronic band with the hedonist appetites of American rock pigs, Depeche Mode started partying so hard in the early '80s, and carried on for so long, the wonder is it took them until 1994 to come to the brink of falling apart.

When Dave Gahan's problems became public, they buried the long-running perception of the band as a faintly ludicrous, faux-doomy pop act with a penchant for black leather. Maybe it's their sartorial quirks over the years, or their preference for synthesizers over guitars, but Britain has always had problems taking Depeche Mode seriously.

Happily, they couldn't care less. They're the most enduring and internationally successful British band of their era. Throughout death, drugs, depression and departing members, they have always had an ear for innovation and a good tune, and have never made a rotten album. In America, they are the acme of Anglophile hip - the band that made musings on death, God and S&M seem at home both in stadiums and on dancefloors. Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails, Slipknot, Korn, Deftones, DJ Shadow and Detroit techno producers have all doffed caps in their direction.

"I was reading Prozac Nation and I think it's us and The Smiths that she [author Elizabeth Wurtzel] accuses of being 'miserable chic'," guffaws Gore, one of those rare people whose laugh sounds exactly like "ha ha ha". "But we just tried to bring some element of reality into pop music."

Last edited: