You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

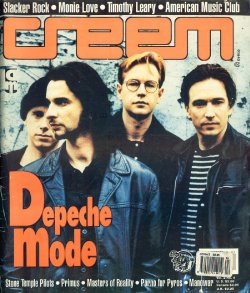

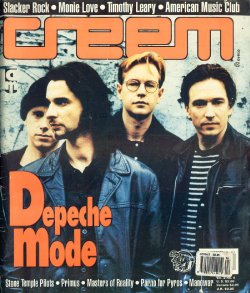

Depeche Mode Mode Squad (Creem, 1993)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1993 creem mode squad

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Of synth-pop’s videogenic pioneers, only Depeche Mode’s microchip melodies spawned long-lived commercial hurrah. Perhaps DM has its own personal Jesus. After all, none of its trail-blazing early-‘80s British peers have had it so good. The Human League remains exiled from the charts. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark floundered after the Pretty in Pink sound-track and eventually split. Soft Cell’s fifteen minutes of fame only lasted about three. Depeche Mode, however, continued to thrive long after the electronic bleeps of Kajagoogoo, A Flock of Seagulls, and Heaven 17 had long faded into dated echoes.Don't let the uninspired, cliche-ridden opening fool you. What follows is a thorough interview full of intelligent questions examining the band from every conceivable angle: songwriting, studio, touring, fanbase, personal lives, business. The interviewer keeps his questioning unobtrusive and allows the band to come out with detailed answers, which is the real strength of this piece.

" But we just gradually evolved, and I can honestly say I believe every one of our albums has gotten better. I think fans see an evolution there and tend to stick with us because they realize we are always trying to break new ground. "

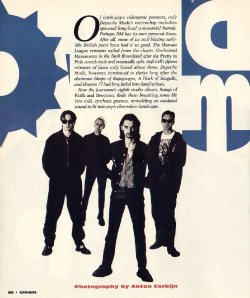

Many thanks to Doreen in Germany, a.k.a. Goregirl, for kindly supplying the scans of this article.

Now the foursome’s eighth studio album, Songs of Faith And Devotion, finds them breathing some life into cold, synthetic grooves, remodelling an outdated sound to fit into pop’s chameleon landscape.

Synth-pop, grunge and arena rock mingle on the rumbling lead single, “I Feel You”. Live gospel singers embellish the cathedral-rock of “Get Right With Me”, while “One Caress” presents a 28-piece orchestra and a nearly human vocal from group member Martin Gore. The album, though not a completely skewed Depeche Mode excursion, doesn’t sink in until one lives with it a while.

David Gahan, who routinely functions as the band’s mouthpiece, considers it to be a “solid-sounding album”, Depeche Mode’s finest work. At home on a stormy L.A. eve, he elaborates a bit over the phone: “Each song has its own special atmosphere, and you’re kind of taken through this journey.” Songs of Faith and Devotion is a reaction to more hardcore electronic trends, he says, “a very song-based album”.

The seeds which sprouted Depeche Mode were planted in 1980 in Basildon, England. Not yet out of their teens, the original foursome – Gahan, Gore, Andrew Fletcher, and songwriter Vince Clarke – formed a “rhythm machine” with guitar, bass, and one synthesizer.

How could the critics not hate them? Some balked at the band’s artificial heart, others blasted Depeche Mode concerts, where various sounds materialized without noticeable human effort. Rolling Stone described their 1981 debut, Speak and Spell, as “robot-pop product”. The album still scaled the U.K. album chart and spawned three hit singles, including the ever-popular “Just Can’t Get Enough”. Nevermind the critics.

Clarke, then a road-shy studio addict, stepped aside after Speak and Spell to for Yazoo with Alison Moyet (and later Erasure with Andy Bell). Gore replaced him as the band’s primary songwriter. For A Broken Frame, the follow-up which Gore calls “a real mish-mash”, he dug up songs he had written at 16. “I think it was definitely a blessing in disguise for me, but I don’t particularly rate A Broken Frame as a great album”, the seasoned writer now says. “It took me awhile to actually find a footing. I pretty much like all of our albums from (1986’s) Black Celebration onwards.”

Alan Wilder – attracted by the Melody Maker ad: “Name Band. Synthesizer. Must be under 21” – joined as Depeche Mode’s musical architect in 1982, despite being an advanced 22 years old. Says Wilder, with typical candour, of earliest Depeche Mode: “I wasn’t magically attracted to the music. I was in such a bad financial state that I would have taken any job that came along.”

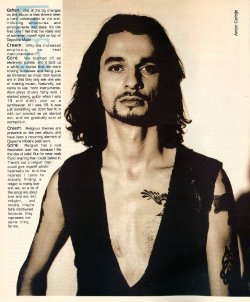

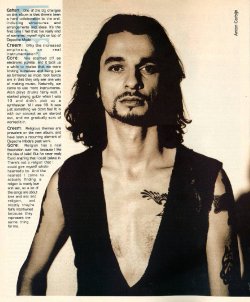

Because the band is blessed not only with striking songs but also a charismatic visual image possessed of the assured swagger and strut of a young Mick Jagger, Depeche Mode’s electronic pulse ticks on 11 years later. Among early synth-pop’s effeminate poster boys, former window design student Gahan emerged as the movement’s closest thing to a sex god, cast as leading man in the wet dreams of pubescent girls – and maybe a few boys. At the close of a 1990 concert at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, an audience member even presented Gahan with a sign that read “Dave Is Sex”. Today, Gahan remembers the incident as “a buzz”.

And who can overlook Gore, Gahan’s androgynous, S&M-clad antithesis? Gore was dressing the part of master/servant long before Madonna bought her first set of whips and chains. Gore explains the persona as an obvious extension of his personality and a reaction against standard machismo rock’n’roll. “I’ve always been aware of the monotony of stage shows in general and just try in a small way to inject some, for want of a better word, glamour,” he says. “I’ve always really liked this non-macho look. The rest of the band put up with quite a lot in the past, (but) they never said to me, ‘I don’t think you should wear that.’ They sort of went along with what I was trying to do.” [1]

[1] - I'm not so sure about that, Martin. I've come across quite a few instances of the band members saying they freaked out at what you were wearing, but then it dawned on them that the more they told you not to do something, the more you'd do it anyway....

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

A second possible reason for Depeche Mode’s continued good fortune is the band’s ass-kicking live reputation. Ten years ago MTV plotted the direction of popular music. Nothing back then sold a band to pop’s trendy masses like a splashy video. Think of any early Duran Duran song titles (“Hungry Like The Wolf” or, say, “Girls on Film”) and the video probably comes to mind before the melody. But these are the Lollapalooza days. Every week MTV presents a new face to watch. Who can keep up? Upstart bands like Pearl Jam and Spin Doctors develop their loyal, dependable fan base on the road. And the 1989 tour film 101, a document of 101 concerts, established Depeche Mode as true road warriors.

Depeche Mode has also survived merely by surviving. During the early ‘80s, the band’s elaborately coiffed synth-pop kin were a dime a dozen. But today, Depeche Mode is a member of a rare species. Techno, industrial and neo-disco outfits such as Nine Inch Nails, Jesus Jones, and Moby are at the forefront of a computer-driven pop obsessed with beats per minute. Suddenly the members of Depeche Mode are elder statesmen, an anomaly in the biz.

On the eve of the release of Songs of Faith and Devotion, Wilder, Fletcher, Gahan and Gore discussed their profitable commodity, which once seemed destined for the one-hit-wonder bin but instead earned a double-digit life span.

Creem: How do you think Depeche Mode, against all odds, outlived its early peers and survived into the ‘90s?

Wilder: I think the key to our longevity is that we’ve been consistently able to write songs. Most of the groups have disappeared simply because they ran out of song ideas, particularly the Human League, who just seemed to dry out.

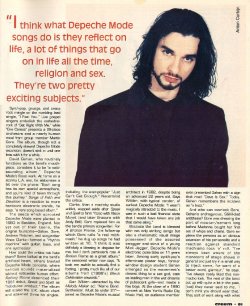

Gahan: I think what Depeche Mode songs do is they reflect on life, a lot of things that go on in life all the time, religion and sex. They’re two pretty exciting subjects.

Fletcher: We tried to avoid the image thing to a certain extent and being tagged with all those bands. It’s like any trend if you get involved in it. When the trend goes, you end up in trouble.

Gore: All the groups we were lumped together with were not anything like us anyway. It was a mistake then that we were actually put in the same bag. But we just gradually evolved, and I can honestly say I believe every one of our albums has gotten better. I think fans see an evolution there and tend to stick with us because they realize we are always trying to break new ground.

Gahan: We’re four pretty powerful people when we’re together in a room, and I think that’s one of the reasons we’ve survived so long as well.

Creem: Depeche Mode’s fans are a particular breed. They are obsessive, perhaps irrationally so. How do you deal with that type of fanatical adulation?

Gore: It’s very flattering, but at the same time I do find it slightly worrying because I’ve never personally been that obsessive about anything. I’ve always loved music, and when I was younger I was interested in certain bands and certain singers, but I never got that fanatical about them. I’ve never even asked for an autograph. It didn’t interest me.

Gahan: I think there’s a lot of people who come to the concerts that get very into the music, and they’re in the spirit of Depeche Mode and the feeling that’s there. It’s a special feeling at Depeche Mode concerts. Anyone who’s been to one will know what I’m talking about.

Wilder: There seems to be a tendency with Depeche Mode fans that they’re either all the-way fans or they hate us completely.

Fletcher: It takes a lot of pressure off us. It enables us to be not as safe, because we know the fans are going to buy the records.

Creem: How about the 1990 mob incident at the album signing in Los Angeles? Thousands of fans showed up at the Wherehouse record store, and damages were estimated at $25,000. These are not ordinary everyday fans. [2]

Depeche Mode has also survived merely by surviving. During the early ‘80s, the band’s elaborately coiffed synth-pop kin were a dime a dozen. But today, Depeche Mode is a member of a rare species. Techno, industrial and neo-disco outfits such as Nine Inch Nails, Jesus Jones, and Moby are at the forefront of a computer-driven pop obsessed with beats per minute. Suddenly the members of Depeche Mode are elder statesmen, an anomaly in the biz.

On the eve of the release of Songs of Faith and Devotion, Wilder, Fletcher, Gahan and Gore discussed their profitable commodity, which once seemed destined for the one-hit-wonder bin but instead earned a double-digit life span.

Creem: How do you think Depeche Mode, against all odds, outlived its early peers and survived into the ‘90s?

Wilder: I think the key to our longevity is that we’ve been consistently able to write songs. Most of the groups have disappeared simply because they ran out of song ideas, particularly the Human League, who just seemed to dry out.

Gahan: I think what Depeche Mode songs do is they reflect on life, a lot of things that go on in life all the time, religion and sex. They’re two pretty exciting subjects.

Fletcher: We tried to avoid the image thing to a certain extent and being tagged with all those bands. It’s like any trend if you get involved in it. When the trend goes, you end up in trouble.

Gore: All the groups we were lumped together with were not anything like us anyway. It was a mistake then that we were actually put in the same bag. But we just gradually evolved, and I can honestly say I believe every one of our albums has gotten better. I think fans see an evolution there and tend to stick with us because they realize we are always trying to break new ground.

Gahan: We’re four pretty powerful people when we’re together in a room, and I think that’s one of the reasons we’ve survived so long as well.

Creem: Depeche Mode’s fans are a particular breed. They are obsessive, perhaps irrationally so. How do you deal with that type of fanatical adulation?

Gore: It’s very flattering, but at the same time I do find it slightly worrying because I’ve never personally been that obsessive about anything. I’ve always loved music, and when I was younger I was interested in certain bands and certain singers, but I never got that fanatical about them. I’ve never even asked for an autograph. It didn’t interest me.

Gahan: I think there’s a lot of people who come to the concerts that get very into the music, and they’re in the spirit of Depeche Mode and the feeling that’s there. It’s a special feeling at Depeche Mode concerts. Anyone who’s been to one will know what I’m talking about.

Wilder: There seems to be a tendency with Depeche Mode fans that they’re either all the-way fans or they hate us completely.

Fletcher: It takes a lot of pressure off us. It enables us to be not as safe, because we know the fans are going to buy the records.

Creem: How about the 1990 mob incident at the album signing in Los Angeles? Thousands of fans showed up at the Wherehouse record store, and damages were estimated at $25,000. These are not ordinary everyday fans. [2]

[2] - You can read about that incident in this souvenir of the event.

It should be clarified though that the event didn't lead to $25,000-worth of damages: the bill presented to K-ROQ was for police and paramedic time as well as the cost of cleaning up the rubbish (not actual damage, as far as I'm aware) afterwards.Depeche Mode - 1990-03-20 The Wherehouse

1990-03-20 The Wherehouse The Wherehouse 3/20/1990 (Sire/Reprise PRO-C-4329) is a promotional cassette tape that was presented as an apology to fans who were inconvenienced or suffered minor injuries as a result of the 20 March 1990 Wherehouse record store incident that resulted in a near riot...dmremix.pro

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Fletcher: I suppose we are a band that you can get yourself wrapped up into. The Wherehouse thing, which was a bit close for comfort, was nearly a disaster with the injuries and stuff. But in the end it turned out to be a good publicity stunt.

Gahan: It actually got quite scary. The whole thing got a little bit out of control. There was no way we could have known that there was going to be so many people turn up. They have these huge glass windows and fans were pushing up against the window, You could feel the atmosphere in the place building up. We just all kind of looked at each other and said, ‘We gotta get out of here!’”

Creem: Does manic fan response ever seem silly to you?

Wilder: I don’t pretend to really understand why somebody would go so far in following their favourite group, which can involve days sleeping on the street in order to just get a glimpse of somebody. Because of this position we’re in we only get a chance to come across the more obsessive types. The average fan doesn’t really want to meet you and is quite happy to just buy the record or come to a concert and that’s it.

Creem: How do you return to a life of normalcy after playing in front of more than a million fans?

Gahan: You’re in this funny little world where you can do whatever you like whenever you like. You start getting a bit crazy. You really get into it. You’re a gang and there’s all the crew… and then suddenly you gotta go to the supermarket and get your groceries. You get into that and you forget for a minute that you’re in a band.

Gore: You’ve got to sort of come back to reality and do all kinds of normal things.

Wilder: You find yourself pacing around the room hating to talk in the evening. Then you realize the reason is you’re supposed to be on stage.

Creem: I think 101 and perhaps other media have offered a very limited view of Depeche Mode’s fan base. But your fans aren’t all straight, white, young people. You also have a substantial black and gay following.

Gore: I really don’t understand what the appeal of our music is. When I write a song I try to capture some sort of passion and then try and communicate that with the world, and I’m not aiming it at anyone in particular. I hope someone somewhere understands and likes what I’m trying to say. It seems to work, and I can’t really analyse it more than that. But I would like to think that it doesn’t just appeal to one race or one gender or one sexuality. It should have a broad appeal.

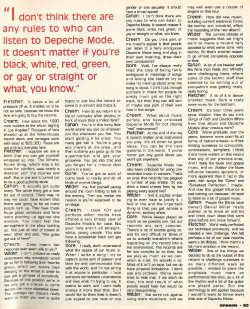

Gahan: I don’t think there are any rules to who can listen to Depeche Mode. It doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, red, green, or gay or straight or what, you know.

Creem: Do you think part of the music’s appeal is that people can listen to a fairly ambiguous Depeche Mode song and plug in their own meaning, draw their own conclusions?

Gore: Well, I’ve always really liked the idea of being fairly ambiguous in meanings of songs and letting the listener try to make his mind up about what the song is about. I think I put enough pointers in there for people to pretty much get on the right track, but then they can still sort of maybe see part of their own lives in the songs.

Gahan: It actually got quite scary. The whole thing got a little bit out of control. There was no way we could have known that there was going to be so many people turn up. They have these huge glass windows and fans were pushing up against the window, You could feel the atmosphere in the place building up. We just all kind of looked at each other and said, ‘We gotta get out of here!’”

Creem: Does manic fan response ever seem silly to you?

Wilder: I don’t pretend to really understand why somebody would go so far in following their favourite group, which can involve days sleeping on the street in order to just get a glimpse of somebody. Because of this position we’re in we only get a chance to come across the more obsessive types. The average fan doesn’t really want to meet you and is quite happy to just buy the record or come to a concert and that’s it.

Creem: How do you return to a life of normalcy after playing in front of more than a million fans?

Gahan: You’re in this funny little world where you can do whatever you like whenever you like. You start getting a bit crazy. You really get into it. You’re a gang and there’s all the crew… and then suddenly you gotta go to the supermarket and get your groceries. You get into that and you forget for a minute that you’re in a band.

Gore: You’ve got to sort of come back to reality and do all kinds of normal things.

Wilder: You find yourself pacing around the room hating to talk in the evening. Then you realize the reason is you’re supposed to be on stage.

Creem: I think 101 and perhaps other media have offered a very limited view of Depeche Mode’s fan base. But your fans aren’t all straight, white, young people. You also have a substantial black and gay following.

Gore: I really don’t understand what the appeal of our music is. When I write a song I try to capture some sort of passion and then try and communicate that with the world, and I’m not aiming it at anyone in particular. I hope someone somewhere understands and likes what I’m trying to say. It seems to work, and I can’t really analyse it more than that. But I would like to think that it doesn’t just appeal to one race or one gender or one sexuality. It should have a broad appeal.

Gahan: I don’t think there are any rules to who can listen to Depeche Mode. It doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, red, green, or gay or straight or what, you know.

Creem: Do you think part of the music’s appeal is that people can listen to a fairly ambiguous Depeche Mode song and plug in their own meaning, draw their own conclusions?

Gore: Well, I’ve always really liked the idea of being fairly ambiguous in meanings of songs and letting the listener try to make his mind up about what the song is about. I think I put enough pointers in there for people to pretty much get on the right track, but then they can still sort of maybe see part of their own lives in the songs.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Creem: What about music purists who have criticized Depeche Mode for not playing ‘real’ instruments?

Fletcher: At the end of the day it doesn’t matter what instrument you play. It’s all down to good ideas. You can be the best guitarist in the world. If you’ve never got any good ideas you won’t get anywhere. [1]

Creem: Depeche Mode has also been criticized for using pre-recorded music in concert. That’s an area that recently has plagued a number of pop artists. Do you think a band cheats fans by not playing every sound live?

Wilder: I find it slightly irritating to even have to justify it. I feel in the end the important thing is that you get across a dynamic, exciting show.

Gore: We’ve always played as much as we possibly can, but our records are very complex. There’s a lot of sounds going on, and it’s very difficult for three of us to actually transform what’s happening on the record into a live environment. The records are far too complex to do that, but we play as much as we can, which is a lot. It’s actually a lot. Most of it isn’t on tape, but we do have physical limitations. I don’t see any problem. We’ve never tried to hide that. If we didn’t do that, the end result of what people would hear live would be very disappointing.

Wilder: But we’re not against using extra musicians, and we may well even use a couple of singers on this tour.

Creem: How did new music, including current electronic forms like techno and industrial, affect the recording of the new album?

Wilder: The current climate of music suggest that we might want to make a record very opposite to what we’ve done, very techno. So that’s another reason to go almost completely opposite to that.

Gahan: A lot of the heavier stuff like Nine Inch Nails and Ministry were challenging ideas, where some of the techno stuff that seemed to be coming out of everywhere was getting really, really boring.

Fletcher: A lot of it is dance-oriented music. Ours is really more music for the bedroom.

Creem: It’s been three years since Violator. How do you think Songs of Faith and Devotion differs from that album and Depeche Mode’s other previous work?

Gore: We’ve gradually, over the years, become more open to all forms of instrumentation and not limiting ourselves to computers, synthesizers, samplers. I think that’s more evident on this record than any of our previous ones. And I really like blues and gospel music, and on Violator the blues influence became apparent, or more apparent than it had in the past, with songs like “Clean” and “Sweetest Perfection”, maybe. And now this gospel influence is just coming out because I do tend to listen to a lot of gospel music.

Gahan: People like (Mute label owner) Daniel Miller really pushed us to move on and try and break down ideas that were done before and move forward.

Fletcher: We’d really perfected our technique previously, and we needed a new challenge. We felt perhaps a lot of our past records were a bit lifeless. I think there’s a lot more emotion in the record.

Wilder: One of the things we decided to do at the outset of this record is challenge ourselves in as many different ways as possible. I wanted to place the emphasis much more on performance this time, so a lot of the rhythm and a lot of the guitar are played parts. But the technology is still applied because I wouldn’t want to throw away that side of Depeche Mode.

Gahan: One of the big changes on this album is that there’s been a hard collaboration to the end, including structures and arrangements and ideas. It’s the first time I feel that I’ve really kind of slammed myself right on top of Depeche Mode.

Fletcher: At the end of the day it doesn’t matter what instrument you play. It’s all down to good ideas. You can be the best guitarist in the world. If you’ve never got any good ideas you won’t get anywhere. [1]

Creem: Depeche Mode has also been criticized for using pre-recorded music in concert. That’s an area that recently has plagued a number of pop artists. Do you think a band cheats fans by not playing every sound live?

Wilder: I find it slightly irritating to even have to justify it. I feel in the end the important thing is that you get across a dynamic, exciting show.

Gore: We’ve always played as much as we possibly can, but our records are very complex. There’s a lot of sounds going on, and it’s very difficult for three of us to actually transform what’s happening on the record into a live environment. The records are far too complex to do that, but we play as much as we can, which is a lot. It’s actually a lot. Most of it isn’t on tape, but we do have physical limitations. I don’t see any problem. We’ve never tried to hide that. If we didn’t do that, the end result of what people would hear live would be very disappointing.

Wilder: But we’re not against using extra musicians, and we may well even use a couple of singers on this tour.

Creem: How did new music, including current electronic forms like techno and industrial, affect the recording of the new album?

Wilder: The current climate of music suggest that we might want to make a record very opposite to what we’ve done, very techno. So that’s another reason to go almost completely opposite to that.

Gahan: A lot of the heavier stuff like Nine Inch Nails and Ministry were challenging ideas, where some of the techno stuff that seemed to be coming out of everywhere was getting really, really boring.

Fletcher: A lot of it is dance-oriented music. Ours is really more music for the bedroom.

Creem: It’s been three years since Violator. How do you think Songs of Faith and Devotion differs from that album and Depeche Mode’s other previous work?

Gore: We’ve gradually, over the years, become more open to all forms of instrumentation and not limiting ourselves to computers, synthesizers, samplers. I think that’s more evident on this record than any of our previous ones. And I really like blues and gospel music, and on Violator the blues influence became apparent, or more apparent than it had in the past, with songs like “Clean” and “Sweetest Perfection”, maybe. And now this gospel influence is just coming out because I do tend to listen to a lot of gospel music.

Gahan: People like (Mute label owner) Daniel Miller really pushed us to move on and try and break down ideas that were done before and move forward.

Fletcher: We’d really perfected our technique previously, and we needed a new challenge. We felt perhaps a lot of our past records were a bit lifeless. I think there’s a lot more emotion in the record.

Wilder: One of the things we decided to do at the outset of this record is challenge ourselves in as many different ways as possible. I wanted to place the emphasis much more on performance this time, so a lot of the rhythm and a lot of the guitar are played parts. But the technology is still applied because I wouldn’t want to throw away that side of Depeche Mode.

Gahan: One of the big changes on this album is that there’s been a hard collaboration to the end, including structures and arrangements and ideas. It’s the first time I feel that I’ve really kind of slammed myself right on top of Depeche Mode.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Creem: Why the increased emphasis on real instrumentation?

Gore: We started off as electronic purists, and it took us a while to realise that we were limiting ourselves and being just as blinkered as most rock bands are in that they only see one way of making music. Naturally, we came to use more instruments. Alan plays drums fairly well. I started playing guitar when I was 13 and didn’t pick up a synthesizer ‘til I was 18. It was just something we didn’t feel fit in with our concept as we started out, and we gradually sort of worked it in.

Creem: Religious themes are prevalent on the new album, and have been a recurring element of Depeche Mode’s past work.

Gore: religion has a real fascination over me, because I like the idea of belief. But I’ve never really found anything that I could believe in. There’s not a religion that I could give myself wholeheartedly to. And the nearest I come to actually finding a religion is mainly love and sex, so a lot of the songs are about love and sex and religion, and mostly they’re fairly intertwined because they represent the same thing for me.

Creem: How about the idea of dominance and submission. That also pops up from time to time.

Gore: Domination and submission is just something that happens all the time in all kinds of relationships, from individual personal relationships to more global worldwide things. I’ve always tried to be realistic in the songs, and that’s often misconstrued as depressing, but I’ve always combatted that by saying I’m not being depressing, I’m being realistic. Therefore, I write in minor keys because life is a minor key.

Creem: You think so?

Gore: I think so, yeah. If you’re gonna be realistic about it. It’s not happy all the time, you know. I think a lot of music is falsely optimistic.

Creem: But what about the dance beat behind those minor keys. In 101 there was a scene where some fans were bopping around to “Nothing”. That song is pretty heavy. Do you think the messages go over their heads?

Gore: As I said, it’s realistic, but at the same time I always offer light at the end of the tunnel, I think, in the lyrics and in the way the music is constructed. If you just have a depressing outlook on life then everything is just too futile. You might as well just give up. And I don’t believe that. I think there’s always something to find hope in. You’ve always gotta have faith in something.

Gahan: Just because a song is asking some questions about subjects that might appear a bit risky to some people doesn’t mean that you can’t mix that with something else. There are times when fans will be sitting and listening to the lyrics, but there are other times when they’re just listening to the beat.

Creem: You’ve never appeared on the cover of a studio album until now. Why not?

Fletcher: We always thought that covers date. If you see a Duran Duran cover in 1981 you think it looks awful. Not anything like they are now. We have always wanted to make sure we don’t date. That our records are relevant now.

Gore: This time, we decided for the first time to break that rule, but it’s still done very tastefully, the colours on the album are very sort of Catholic colours to get across this feeling of religion that’s touched on the title. We’re still fairly obscured. It’s not just a question of us thrusting our faces on the world.

Gore: We started off as electronic purists, and it took us a while to realise that we were limiting ourselves and being just as blinkered as most rock bands are in that they only see one way of making music. Naturally, we came to use more instruments. Alan plays drums fairly well. I started playing guitar when I was 13 and didn’t pick up a synthesizer ‘til I was 18. It was just something we didn’t feel fit in with our concept as we started out, and we gradually sort of worked it in.

Creem: Religious themes are prevalent on the new album, and have been a recurring element of Depeche Mode’s past work.

Gore: religion has a real fascination over me, because I like the idea of belief. But I’ve never really found anything that I could believe in. There’s not a religion that I could give myself wholeheartedly to. And the nearest I come to actually finding a religion is mainly love and sex, so a lot of the songs are about love and sex and religion, and mostly they’re fairly intertwined because they represent the same thing for me.

Creem: How about the idea of dominance and submission. That also pops up from time to time.

Gore: Domination and submission is just something that happens all the time in all kinds of relationships, from individual personal relationships to more global worldwide things. I’ve always tried to be realistic in the songs, and that’s often misconstrued as depressing, but I’ve always combatted that by saying I’m not being depressing, I’m being realistic. Therefore, I write in minor keys because life is a minor key.

Creem: You think so?

Gore: I think so, yeah. If you’re gonna be realistic about it. It’s not happy all the time, you know. I think a lot of music is falsely optimistic.

Creem: But what about the dance beat behind those minor keys. In 101 there was a scene where some fans were bopping around to “Nothing”. That song is pretty heavy. Do you think the messages go over their heads?

Gore: As I said, it’s realistic, but at the same time I always offer light at the end of the tunnel, I think, in the lyrics and in the way the music is constructed. If you just have a depressing outlook on life then everything is just too futile. You might as well just give up. And I don’t believe that. I think there’s always something to find hope in. You’ve always gotta have faith in something.

Gahan: Just because a song is asking some questions about subjects that might appear a bit risky to some people doesn’t mean that you can’t mix that with something else. There are times when fans will be sitting and listening to the lyrics, but there are other times when they’re just listening to the beat.

Creem: You’ve never appeared on the cover of a studio album until now. Why not?

Fletcher: We always thought that covers date. If you see a Duran Duran cover in 1981 you think it looks awful. Not anything like they are now. We have always wanted to make sure we don’t date. That our records are relevant now.

Gore: This time, we decided for the first time to break that rule, but it’s still done very tastefully, the colours on the album are very sort of Catholic colours to get across this feeling of religion that’s touched on the title. We’re still fairly obscured. It’s not just a question of us thrusting our faces on the world.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Creem: So why make a movie? That certainly put those faces in the spotlight.

Gore: We happened to tour, and I think it’s just good to document that. It’s something that happened in our lives, and I think we’re quite disappointed that we didn’t film the last tour. It would have looked a lot more visually interesting because we used films behind us onstage, which gave the stage a real depth.

Creem: You’ve been with Mute Records from the beginning, and the extent of your recording contract is a handshake. (The band gets 50 percent of profits and isn’t bound to record exclusively for Mute.) And you have no manager. What an odd business decision!

Gore: It just means we have total control over everything that we do.

Wilder: Had Depeche Mode signed to CBS or EMI, we would probably have been milked dry and forced into some kind of management.

Gore: Working with Mute has given us total freedom as well because Daniel Miller is more of a friend who may advise us and say, ‘That may be a good time release a single and an album,’ or whatever, but there’s absolutely no pressure. He just leaves it up to us to do whatever we want to do.

Fletcher: They’ve allowed us to develop at our own pace.

Creem: So they didn’t rush million-selling success?

Fletcher: You’ve got a band like Pearl Jam or Nirvana, and they’re massive within a year or so, and you can see that their personal lives suffer.

Creem: The members of Depeche Mode are now in their thirties and married with children. How did approaching and passing 30 affect your music?

Gore: I don’t really place too much importance on it. I don’t think I’ve particularly changed that much by aging. I have a 20-month old daughter now, and I think that’s probably changed me more than the fact that I’ve passed 30. The new album does have a more positive outlook to it, and I think that’s mainly due to my daughter.

Fletcher: I think we’ve lost a lot of the naive enthusiasm. You gain experience, but you lose enthusiasm. Because of that we won’t be making as many records in the next 10 years. There won’t be as many tours because we’ve lost that bubbly enthusiasm.

Wilder: You start hitting 30, and you want to do some other things, and you want to sort out some of your relationships, have children.

Fletcher: We had to ask ourselves before this album, ‘Are we hungry enough?’ It’s a question a band has to ask itself all the time. But then you do become staid like Genesis, like Sting, Phil Collins. We’re still craving a certain amount of respect. Our egos aren’t totally satisfied yet.

Gahan: People seem to forget that this band has survived now for 13 years, and people have the same image of you for a long while. It’s incredible how much emphasis is based on look, really, when it comes to being in a band.

Creem: In a particularly memorable 101 scene, some kinds argue about whether fashion should be considered art. Their discussion highlights an interesting question about the conflict between the need to be true to yourself and create uncompromising art and the desire to be commercially successful. How has that struggle affected you?

Gore: I’ve never really tried to aim the songs or the music to anything in particular other than to please myself. Maybe the end result of what we present to the rest of the world is a compromise because all band situations have to be a compromise to a certain extent. But other than that we don’t think at all about fashion.

Fletcher: This is our job now, so we have to make money. It’s a very capitalistic industry we’re in. If you sell five million records you make a lot of money; if you sell one hundred thousand you don’t.

Gore: Andy isn’t really particularly a musician, so he tends to deflect a lot of that from the rest of us, and we’re more able to just concentrate on the music. You can’t say that making a sort of fairly spiritual-sounding, and even gospel-sounding, album is particularly trying to please the fans. I don’t think that’s what they want particularly.

Now the public will have its say. In May, fans in Europe will be bouncing in their seats all over again. The United States is next, in September. Gahan can barely conceal his anticipation: “To tour in America is really exciting,” he says eagerly, “And if you do it in the right way you can follow the sun around.”

Gore: We happened to tour, and I think it’s just good to document that. It’s something that happened in our lives, and I think we’re quite disappointed that we didn’t film the last tour. It would have looked a lot more visually interesting because we used films behind us onstage, which gave the stage a real depth.

Creem: You’ve been with Mute Records from the beginning, and the extent of your recording contract is a handshake. (The band gets 50 percent of profits and isn’t bound to record exclusively for Mute.) And you have no manager. What an odd business decision!

Gore: It just means we have total control over everything that we do.

Wilder: Had Depeche Mode signed to CBS or EMI, we would probably have been milked dry and forced into some kind of management.

Gore: Working with Mute has given us total freedom as well because Daniel Miller is more of a friend who may advise us and say, ‘That may be a good time release a single and an album,’ or whatever, but there’s absolutely no pressure. He just leaves it up to us to do whatever we want to do.

Fletcher: They’ve allowed us to develop at our own pace.

Creem: So they didn’t rush million-selling success?

Fletcher: You’ve got a band like Pearl Jam or Nirvana, and they’re massive within a year or so, and you can see that their personal lives suffer.

Creem: The members of Depeche Mode are now in their thirties and married with children. How did approaching and passing 30 affect your music?

Gore: I don’t really place too much importance on it. I don’t think I’ve particularly changed that much by aging. I have a 20-month old daughter now, and I think that’s probably changed me more than the fact that I’ve passed 30. The new album does have a more positive outlook to it, and I think that’s mainly due to my daughter.

Fletcher: I think we’ve lost a lot of the naive enthusiasm. You gain experience, but you lose enthusiasm. Because of that we won’t be making as many records in the next 10 years. There won’t be as many tours because we’ve lost that bubbly enthusiasm.

Wilder: You start hitting 30, and you want to do some other things, and you want to sort out some of your relationships, have children.

Fletcher: We had to ask ourselves before this album, ‘Are we hungry enough?’ It’s a question a band has to ask itself all the time. But then you do become staid like Genesis, like Sting, Phil Collins. We’re still craving a certain amount of respect. Our egos aren’t totally satisfied yet.

Gahan: People seem to forget that this band has survived now for 13 years, and people have the same image of you for a long while. It’s incredible how much emphasis is based on look, really, when it comes to being in a band.

Creem: In a particularly memorable 101 scene, some kinds argue about whether fashion should be considered art. Their discussion highlights an interesting question about the conflict between the need to be true to yourself and create uncompromising art and the desire to be commercially successful. How has that struggle affected you?

Gore: I’ve never really tried to aim the songs or the music to anything in particular other than to please myself. Maybe the end result of what we present to the rest of the world is a compromise because all band situations have to be a compromise to a certain extent. But other than that we don’t think at all about fashion.

Fletcher: This is our job now, so we have to make money. It’s a very capitalistic industry we’re in. If you sell five million records you make a lot of money; if you sell one hundred thousand you don’t.

Gore: Andy isn’t really particularly a musician, so he tends to deflect a lot of that from the rest of us, and we’re more able to just concentrate on the music. You can’t say that making a sort of fairly spiritual-sounding, and even gospel-sounding, album is particularly trying to please the fans. I don’t think that’s what they want particularly.

Now the public will have its say. In May, fans in Europe will be bouncing in their seats all over again. The United States is next, in September. Gahan can barely conceal his anticipation: “To tour in America is really exciting,” he says eagerly, “And if you do it in the right way you can follow the sun around.”

[1] - This is an idea which took a long time to dawn on the band. While, contrary to popular belief, guitars were used from 1983 onwards, the band for some time seemed to have a type of inverted snobbery about using too many 'conventional' instruments, just as many music critics can get sniffy about synths. Alan Wilder, speaking in 1998: "In the early days, we had silly rules about not using guitars, and then we realised it was ridiculous to have any rules about instrumentation. You could use any instrument if it works.

Alan Wilder Unsound Recordings (Sound On Sound, 1998)

UNSOUND RECORDINGS [Sound On Sound, January 1998. Words: Bill Bruce/ Pictures: Uncredited.] An immense, studio-oriented article examining Alan Wilder's work, especially in the light of the Unsound Methods album being released at the time. Alan talks intelligently and in detail about his...dmremix.pro