You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

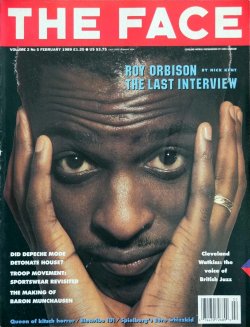

Depeche Mode Modus Operandum (The Face, 1989)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1989 modus operandum the face

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

"The DJ cuts from The Beat Club's "Security" to Front 242 to Black Riot and Depeche Mode's "Strangelove". I change station and Noel's "Silent Morning", a hugely-influential Latin hip hop track, knocks me sideways. Suddenly, it is unmistakeably Depeche Mode's "Leave In Silence". The full extent of the irony starts to hit home. I think of all the desperately crap UK acid records I get through the post and start laughing."

The celebrated article which kicked off an era of Depeche Mode being hailed as pioneers of the house music scene, changing the way the music industry viewed the band in the process. The Face arranged a meeting between Depeche Mode and house DJ Derrick May in order to explore this proposition further. Ultimately, it concedes that Depeche Mode did not 'detonate house', as the cover asks; but the number of big house names nodding towards their influence - both at the time and since - makes this article required reading.

"I used to play Depeche Mode as a DJ, before I even knew the name of the group - their music was very hot at that time, records like 'Strangelove'. We were influenced a lot by their sound. It's real progressive dance, and had this feeling that was sooo European: it was clean and you could dance to it."

- Kevin Saunderson, the man behind Inner City

"They've set the standard in what they do. In America they've been able to please almost everyone, from a guy like me who's a hardcore dance addict, to the stadium crowds. They're right on time, right in synch, and they can't even help it."

- Derrick May, one of the originators of Detroit techno

"I only really played one of their records, but a lot of people I've worked with were influenced by them, especially Jamie Principle. I know that Jesse Saunders was a big fan, and so was Farley (Jackmaster Funk)."

- Frankie Knuckles, DJ at the original Warehouse Club in Chicago and one of house music's founding fathers

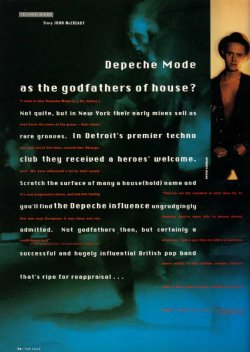

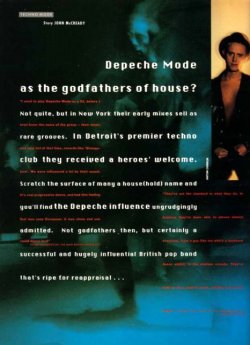

Depeche Mode as the godfathers if house? Not quite, but in New York their early mixes sell as rare grooves. In Detroit's premier techno club they received a heroes' welcome. Scratch the surface of many a house(hold) name and you'll find the Depeche influence ungrudgingly admitted. Not godfathers then, but certainly a successful and hugely influential British pop band that's ripe for reappraisal...

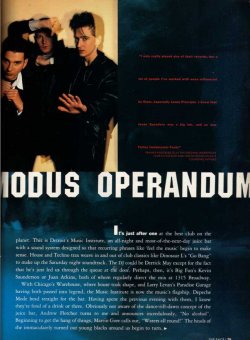

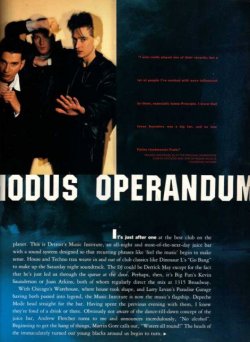

It's just after one at the best club on the planet. This is Detroit's Music Institute, an all-night and most-of-the-next-day juice bar with a sound system designed so that recurring phrases like 'feel the music' begin to make sense. House and Techno trax weave in and out of club classics like Dinosaur L's 'Go Bang' to make up the Saturday night soundtrack. The DJ could be Derrick May except for the fact that he's just led us through the queue at the door. Perhaps, then, it's Big Fun's Kevin Saunderson or Juan Atkins, both of whom regularly direct the mix at 1315 Broadway.

With Chicago's Warehouse, where house took shape, and Larry Levan's Paradise Garage having both passed into legend, the Music Institute is now the music's flagship. Depeche Mode head straight for the bar. Having spent the previous evening with them, I know they're fond of a drink or three. Obviously not aware of the dance-till-dawn concept of the juice bar, Andrew Fletcher turns to me and announces incredulously, "No alcohol". Beginning to get the hang of things, Martin Gore calls out, "Waters all round!" The heads of the immaculately turned out young blacks around us begin to turn.

Despite the fact that we are all beginning to look like death warmed up following last night's late late warehouse rap party in New York, Depeche Mode are very quickly 'recognised'. Within minutes, Martin Gore has a tape from local Techno group Seperate Minds thrust into his hand. Had this been Schoom, The Kool Kat or the Hacienda, the group might have been blanked, laughed at, or even insulted. In Britain, Depeche Mode are a kids' group, a 'pop' group; Bros, but older. In the gun capital of America, the reaction is inevitably different. Will they get shot? Only with a camera.

"Smile, please," says a beautiful young black girl as her friends crowd around the group.

"Oh, God!" says another, "I can't believe it! This is great, Depeche Mode in Detroit... Why?"

Believe me, it's a long story.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

With a career spanning seven albums, what seem like several hundred singles and over nine years, Depeche Mode, despite having almost uniquely combined creative progress with ever-increasing record sales, are second only to the combined forces of Kylie, Cliff and PWL when it comes to being subjected to the acid wit of the pop media. Pieces about the group usually consist of two-part jokes about leather skirts, one part a reference to their New Romantic teatowel-wearing period, and several gratuitous references to Basildon.

Yet in America, they are spoken about in the same reverential tones as New Order and even Kraftwerk. Frankie Knuckles won't deny owning a well-worn copy of "Just Can't Get Enough" and Todd Terry will talk about them as his favourite dance group. In America, Depeche Mode are a phenomenon, a white English 'pop' group respected on the black club scene in New York, Chicago and Detroit through records like their 1983 single "Get The Balance Right" - a $25 'Disco Classic' in Manhattan's hip Downstairs Records. And this is despite the fact that their knowledge of club culture is such that they haven't heard of most of the people who control your night-time soundtrack. Here, they remain a laughing stock thanks to a received impression of them as fools lost in the pop machine.

"We accept that we are partly responsible in creating the problem in Britain," says Andy Fletcher, the group's diplomat and all-round diamond geezer. In the hotel bar in Detroit we begin the interview proper. Depeche Mode are in America viewing the final cut of 101, their first concert movie, which was put together by legendary pop filmaker D. A. Pennebaker. A mixture of documentary and concert footage, it echoes the candid style of the director's Don't Look Back, made during Bob Dylan's early sixties tour of the UK.

It records Depeche Mode's 101st concert held before a 60,000 crowd at the Rosebowl in Pasadena, and illustrates their obvious overground success in America. The film accompanies a new live LP set from the same concert. That job done in New York, here, in the interest of providing another view of a group whose name is always accompanied in British magazines by an italicised cynicism from an unidentified "Ed", Depeche Mode are taking a Techno holiday, their curiosity stirred after hearing some of the city's innovative new dance music. The trip also provides a way of approaching a group who are now in a position to refuse the standard tape-recorder-on-the-table trial.

Having been introduced to the group the day before, I negotiated their guilty-until-proven-innocent reticence at an Indian restaurant, where the hapless Fletcher brought a glass-fronted picture crashing to the ground by leaning where he shouldn't have. Dave Gahan, pissed as a fart at 4.30 in the morning, pronounces me "All right", having decided before my arrival that I would be a bastard in designer shoes who wouldn't get his round in. The fact that most of the people who put The Face together look like refuse collectors seems to come as a great surprise to most people. By the time the tape recorder does make its scheduled appearance, their inbuilt suspicion is at an all-time low. At this point it's decided that there is a difference between the great British music press and me. Stories of disreputable gentlemen of the press in berets begin to flow through, aided by the tongue-loosening properties of potent bottled beers.

"When we began, we couldn't believe that anyone was interested," says Fletch. "And we did every TV show, every interview that came up. We were wrapped up as a pop group, nothing more and nothing less, and we have suffered from that image ever since." He takes time out to explain that there is nothing inherently wrong with pop music. We agree that it has become a simple term of abuse due to the critics' common viewpoint that what is popular is therefore crap: bad logic in anyone's philosophy book. Alan Wilder - who can look as sullen as a Spurs fan on any Saturday afternoon but instead turns out to be another diamond geezer who doesn't get enough sleep - adds that the power of the pop press is such that those who like the group find themselves having to explain why - something I'm used to. New Order, who began life as Joy Division, thereby giving music critics the opportunity to prattle on about cathedrals of sound, are seen in America as similar white dance practicians. In Britain, the respect they have overseas is more than equalled. It's an attitude which frustrates rather than puzzles the group.

The situation seems massively ironic when the full extent of Depeche Mode's American success becomes clear.

Yet in America, they are spoken about in the same reverential tones as New Order and even Kraftwerk. Frankie Knuckles won't deny owning a well-worn copy of "Just Can't Get Enough" and Todd Terry will talk about them as his favourite dance group. In America, Depeche Mode are a phenomenon, a white English 'pop' group respected on the black club scene in New York, Chicago and Detroit through records like their 1983 single "Get The Balance Right" - a $25 'Disco Classic' in Manhattan's hip Downstairs Records. And this is despite the fact that their knowledge of club culture is such that they haven't heard of most of the people who control your night-time soundtrack. Here, they remain a laughing stock thanks to a received impression of them as fools lost in the pop machine.

"We accept that we are partly responsible in creating the problem in Britain," says Andy Fletcher, the group's diplomat and all-round diamond geezer. In the hotel bar in Detroit we begin the interview proper. Depeche Mode are in America viewing the final cut of 101, their first concert movie, which was put together by legendary pop filmaker D. A. Pennebaker. A mixture of documentary and concert footage, it echoes the candid style of the director's Don't Look Back, made during Bob Dylan's early sixties tour of the UK.

It records Depeche Mode's 101st concert held before a 60,000 crowd at the Rosebowl in Pasadena, and illustrates their obvious overground success in America. The film accompanies a new live LP set from the same concert. That job done in New York, here, in the interest of providing another view of a group whose name is always accompanied in British magazines by an italicised cynicism from an unidentified "Ed", Depeche Mode are taking a Techno holiday, their curiosity stirred after hearing some of the city's innovative new dance music. The trip also provides a way of approaching a group who are now in a position to refuse the standard tape-recorder-on-the-table trial.

Having been introduced to the group the day before, I negotiated their guilty-until-proven-innocent reticence at an Indian restaurant, where the hapless Fletcher brought a glass-fronted picture crashing to the ground by leaning where he shouldn't have. Dave Gahan, pissed as a fart at 4.30 in the morning, pronounces me "All right", having decided before my arrival that I would be a bastard in designer shoes who wouldn't get his round in. The fact that most of the people who put The Face together look like refuse collectors seems to come as a great surprise to most people. By the time the tape recorder does make its scheduled appearance, their inbuilt suspicion is at an all-time low. At this point it's decided that there is a difference between the great British music press and me. Stories of disreputable gentlemen of the press in berets begin to flow through, aided by the tongue-loosening properties of potent bottled beers.

"When we began, we couldn't believe that anyone was interested," says Fletch. "And we did every TV show, every interview that came up. We were wrapped up as a pop group, nothing more and nothing less, and we have suffered from that image ever since." He takes time out to explain that there is nothing inherently wrong with pop music. We agree that it has become a simple term of abuse due to the critics' common viewpoint that what is popular is therefore crap: bad logic in anyone's philosophy book. Alan Wilder - who can look as sullen as a Spurs fan on any Saturday afternoon but instead turns out to be another diamond geezer who doesn't get enough sleep - adds that the power of the pop press is such that those who like the group find themselves having to explain why - something I'm used to. New Order, who began life as Joy Division, thereby giving music critics the opportunity to prattle on about cathedrals of sound, are seen in America as similar white dance practicians. In Britain, the respect they have overseas is more than equalled. It's an attitude which frustrates rather than puzzles the group.

The situation seems massively ironic when the full extent of Depeche Mode's American success becomes clear.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

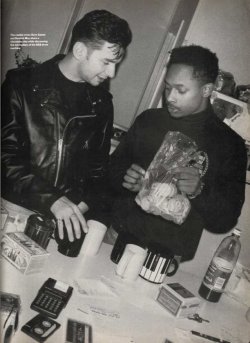

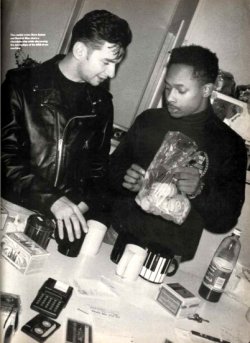

Derrick May, one of the originators of Techno, who records as Mayday, Rhythim Is Rhythim and R-Tyme, looks after us in Detroit. He's keen to talk to a group he sees as part of America's underground dance scene. "They have dance in their blood," he says. Aligning them with Nitzer Ebb, New Order, DAF, Yello and the rest of the European rhythm invaders, Derrick believes that Depeche Mode were an important part of the club collision that evolved as Chicago house. The Detroit Techno sound was created on a musical diet of Clinton and European rhythm-based tracks like Depeche's classic "People Are People". This intercontinental collision at the heart of Chicago house, Techno and Todd Terry's New York sample sound is the key to the future of contemporary American dance music.

When I mention Todd Terry to Andy Fletcher and he asks me who he is, it's clear that the group themselves are blissfully unaware of their influence. Perhaps the fact that they remain largely uninterested, preferring to concentrate on creating more of the same, is the key to their dance success. Dave Gahan relates that their much sought-after 12-inch mixes were created not for clubs, but for bedroom listening.

"We had to do these 12-inch records so we made sure they were interesting all the way. We spent a lot of time putting them together so that people would want to listen to them from end to end."

The dub techniques and intuitively rhythm-conscious sound collages that resulted are landmarks in the development of the house sound. Whether you like it or not, "Just Can't Get Enough" is a dance masterpiece which like "Disco Circus", "Love Is The Message" and Klien And MBO's "Dirty Talk" helped shape the most feted club sound of the decade.

Most of the other British groups who emerged from the white dance boom of the early Eighties would have paid dearly to hear their records smoothed into a mastermix on New York's Kiss and WBLS radio stations or even to share a minibus with Derrick May. Duran Duran courted the attentions of the Chic Organisation, yet they have as much to do with current club culture as ABC, who recorded a tribute to the house sound called "Chicago". The Human League, always mindful of their club success, are the only British group to come close to Depeche Mode's American standing in the clubs.

As musicians with a genuine love of black music, they tried to build on that success by attempting to mould their very European awkwardness into something more soulful. Millions of pounds were spent on the "Crash" album, produced by Minneapolis studio gods Jam and Lewis. The move did nothing but upset a black audience almost bored by a million and one immaculate arrangements and endlessly capable voices. They want to hear an English accent and a synthesiser and be persuaded by a different sound. They wanted Phil Oakey to be Phil Oakey singing "Being Boiled". When Phil Oakey nearly became Alexander O'Neal singing "Human" they lost interest. The Human League blew it by trying to assimilate a sound their American audience already knew by heart.

Depeche Mode, far from capitalising on their appeal, believe they too are about to upset their ironic alliance with US club culture. Alan Wilder tells me that the new material they are working on builds on the slower tempos of the "Music For The Masses" LP. Martin Gore, the group's only songwriter who, curiously, listens to old rock and roll for inspiration, believes that Depeche Mode aren't capable of making dance music anyway.

"We can't create dance music, and I don't think we've ever really tried. We honestly wouldn't know where to start."

Two days later, I'm in a car in Miami listening to a radio mix show. The DJ cuts from The Beat Club's "Security" to Front 242 to Black Riot and Depeche Mode's "Strangelove". I change station and Noel's "Silent Morning", a hugely-influential Latin hip hop track, knocks me sideways. Suddenly, it is unmistakeably Depeche Mode's "Leave In Silence". The full extent of the irony starts to hit home. I think of all the desperately crap UK acid records I get through the post and start laughing.

As usual, with the tape recorder switched off people start telling good stories. Our planned visit to Majestics, an Anglo-obsessed "English Beat" club which Derrick tells us is haunted by Numan clones and tea-towelled futurists, is the subject of comic anticipation. The group admit they benefitted from their association with the kilt and make-up scene of the early Eighties. But as the tag became a critical liability and Depeche Mode grew into the wilful pop stylists of "Leave In Silence" and the brilliant "Get The Balance Right", it proved hard to shake.

Dave Gahan recalls a concert in Paris about two years after the whole scene had died. Arriving at the hall, they couldn't help but notice huge posters announcing DEPECHE MODE: KINGS OF THE NEW ROMANTICS.

When we get to Majestics, Bauhaus's 'Bela Lugosi' is stirring up the dancefloor. This is Retro Anglo or 'Nu Musik', and these are the people who have helped create a market for groups like Information Society who try to recreate the awkwardness and the essential Englishness of the early Depeche Mode sound. As a man in a green fishtail parka and a flat cap passes me I am mysteriously reminded of Chicago's Bedrock Club, where one of the main attractions of the house nation seems to be the exotic charms of Warney's Red Barrel. A big man in mascara crushes past and I decide that Depeche Mode may not leave without giving the assembled crowd a quick blast of "Photographic", an early Basildon New Romantic classic. Here, as in the Music Institute, which we head for after a minute or two of "Just Can't Get Enough" signals we've been spotted, the autograph requests begin. We drive to the Institute with the group discussing their music and the Techno sound with Derrick May. They want to know why almost every house track utilises the very specific sound of the Roland 808 drum machine. Later, Dave Gahan tells me that they don't really feel part of what's happening.

"Still, I can feel the excitement of it. In a way it's confirmed that what we are doing has been right all along. House seems to me the most important musical development of the Eighties, in that it's combined dance and the electronic sound. What Derrick is doing looks to the future."

With a grin on his face, Fletch recalls a British interview where the opening question was "What's it like to be playing old-fashioned music?"

"This was before house - a really dark time for electronic music. At the time electronic was a dirty word. People were talking about guitars a lot. It was like, 'How does it feel to be finished?' Dave nearly clobbered the guy!"

As we approach the club Dave is taking the piss out of Derrick's hyperactivity and Derrick is taking the piss out of his accent. A mention of Kraftwerk changes the subject and provides the best explanation for the phenomenon that is Depeche Mode's American club success. While most British groups dealing with America try to be American, Depeche Mode are, like Derrick May and Todd Terry, still listening intently to Kraftwerk and chasing the elusive European electro sound created and perfected by the masters of Dusseldorf. The admiration for Kling Klang techno ties them all together and makes sense of the line to be drawn between Basildon and Detroit, between Depeche Mode's "New Life" and Derrick May's "Nude Photo".

Of course, there is another way of looking at it. "Some of our records have a good beat and that's about the end of it," says Dave Gahan.

When I mention Todd Terry to Andy Fletcher and he asks me who he is, it's clear that the group themselves are blissfully unaware of their influence. Perhaps the fact that they remain largely uninterested, preferring to concentrate on creating more of the same, is the key to their dance success. Dave Gahan relates that their much sought-after 12-inch mixes were created not for clubs, but for bedroom listening.

"We had to do these 12-inch records so we made sure they were interesting all the way. We spent a lot of time putting them together so that people would want to listen to them from end to end."

The dub techniques and intuitively rhythm-conscious sound collages that resulted are landmarks in the development of the house sound. Whether you like it or not, "Just Can't Get Enough" is a dance masterpiece which like "Disco Circus", "Love Is The Message" and Klien And MBO's "Dirty Talk" helped shape the most feted club sound of the decade.

Most of the other British groups who emerged from the white dance boom of the early Eighties would have paid dearly to hear their records smoothed into a mastermix on New York's Kiss and WBLS radio stations or even to share a minibus with Derrick May. Duran Duran courted the attentions of the Chic Organisation, yet they have as much to do with current club culture as ABC, who recorded a tribute to the house sound called "Chicago". The Human League, always mindful of their club success, are the only British group to come close to Depeche Mode's American standing in the clubs.

As musicians with a genuine love of black music, they tried to build on that success by attempting to mould their very European awkwardness into something more soulful. Millions of pounds were spent on the "Crash" album, produced by Minneapolis studio gods Jam and Lewis. The move did nothing but upset a black audience almost bored by a million and one immaculate arrangements and endlessly capable voices. They want to hear an English accent and a synthesiser and be persuaded by a different sound. They wanted Phil Oakey to be Phil Oakey singing "Being Boiled". When Phil Oakey nearly became Alexander O'Neal singing "Human" they lost interest. The Human League blew it by trying to assimilate a sound their American audience already knew by heart.

Depeche Mode, far from capitalising on their appeal, believe they too are about to upset their ironic alliance with US club culture. Alan Wilder tells me that the new material they are working on builds on the slower tempos of the "Music For The Masses" LP. Martin Gore, the group's only songwriter who, curiously, listens to old rock and roll for inspiration, believes that Depeche Mode aren't capable of making dance music anyway.

"We can't create dance music, and I don't think we've ever really tried. We honestly wouldn't know where to start."

Two days later, I'm in a car in Miami listening to a radio mix show. The DJ cuts from The Beat Club's "Security" to Front 242 to Black Riot and Depeche Mode's "Strangelove". I change station and Noel's "Silent Morning", a hugely-influential Latin hip hop track, knocks me sideways. Suddenly, it is unmistakeably Depeche Mode's "Leave In Silence". The full extent of the irony starts to hit home. I think of all the desperately crap UK acid records I get through the post and start laughing.

As usual, with the tape recorder switched off people start telling good stories. Our planned visit to Majestics, an Anglo-obsessed "English Beat" club which Derrick tells us is haunted by Numan clones and tea-towelled futurists, is the subject of comic anticipation. The group admit they benefitted from their association with the kilt and make-up scene of the early Eighties. But as the tag became a critical liability and Depeche Mode grew into the wilful pop stylists of "Leave In Silence" and the brilliant "Get The Balance Right", it proved hard to shake.

Dave Gahan recalls a concert in Paris about two years after the whole scene had died. Arriving at the hall, they couldn't help but notice huge posters announcing DEPECHE MODE: KINGS OF THE NEW ROMANTICS.

When we get to Majestics, Bauhaus's 'Bela Lugosi' is stirring up the dancefloor. This is Retro Anglo or 'Nu Musik', and these are the people who have helped create a market for groups like Information Society who try to recreate the awkwardness and the essential Englishness of the early Depeche Mode sound. As a man in a green fishtail parka and a flat cap passes me I am mysteriously reminded of Chicago's Bedrock Club, where one of the main attractions of the house nation seems to be the exotic charms of Warney's Red Barrel. A big man in mascara crushes past and I decide that Depeche Mode may not leave without giving the assembled crowd a quick blast of "Photographic", an early Basildon New Romantic classic. Here, as in the Music Institute, which we head for after a minute or two of "Just Can't Get Enough" signals we've been spotted, the autograph requests begin. We drive to the Institute with the group discussing their music and the Techno sound with Derrick May. They want to know why almost every house track utilises the very specific sound of the Roland 808 drum machine. Later, Dave Gahan tells me that they don't really feel part of what's happening.

"Still, I can feel the excitement of it. In a way it's confirmed that what we are doing has been right all along. House seems to me the most important musical development of the Eighties, in that it's combined dance and the electronic sound. What Derrick is doing looks to the future."

With a grin on his face, Fletch recalls a British interview where the opening question was "What's it like to be playing old-fashioned music?"

"This was before house - a really dark time for electronic music. At the time electronic was a dirty word. People were talking about guitars a lot. It was like, 'How does it feel to be finished?' Dave nearly clobbered the guy!"

As we approach the club Dave is taking the piss out of Derrick's hyperactivity and Derrick is taking the piss out of his accent. A mention of Kraftwerk changes the subject and provides the best explanation for the phenomenon that is Depeche Mode's American club success. While most British groups dealing with America try to be American, Depeche Mode are, like Derrick May and Todd Terry, still listening intently to Kraftwerk and chasing the elusive European electro sound created and perfected by the masters of Dusseldorf. The admiration for Kling Klang techno ties them all together and makes sense of the line to be drawn between Basildon and Detroit, between Depeche Mode's "New Life" and Derrick May's "Nude Photo".

Of course, there is another way of looking at it. "Some of our records have a good beat and that's about the end of it," says Dave Gahan.

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63