Showtime!

[Q, Febuary 2006. Words: Johnny Davis. Pictures: Ross Halfin.]

SHOWTIME!

Dave Gahan looks wrecked. Slack of jaw and boggly of eye, he leers upwards. His polka-dot shirt is adrift at nipple-height. His cheeks are hollow, his hair lank and nasty. Years of injecting heroin and cocaine have done him in.

“He didn’t look great, did he?” says Tony Sanchez.

“Now he’s incredibly hot,” says Lisa Andrews. “Have you seen him dance? He’s awesome.”

The singer’s once-sickly features peer out from a framed gold disc for Depeche Mode’s 1993 album Songs Of Faith And Devotion, the never-ending tour which resulted in breakdowns, hospitalisations and overdoses. Today, of course, Gahan couldn’t look healthier. But then, plenty’s changed.

Tony and Lisa are waiting to see the band in Las Vegas’ Hard Rock Hotel, a shrine to the more colourful aspects of rock’n’roll history. Along with several hundred other Depeche Mode fans, they’ve been here all day.

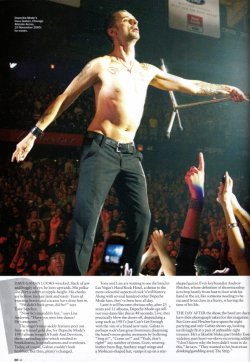

Later it will become obvious why, after 25 years and 11 albums, Depeche Mode can sell out tour dates like this in 48 seconds. Live, they practically blow the doors off, dispatching a song, such as 1981’s Just Can’t Get Enough, with the vim of a brand new tune. Gahan is perhaps rock’s last great frontman; disarming the band’s more gothic moments by hollering “Sing it!”, “Come on!”, and “Yeah, that’s right!” any number of times. Gore, wearing leather bum-flap, feathery angel wings and a Mohican-shaped hat, vamps it up on a star-shaped guitar. Even keyboardist Andrew Fletcher, whose definition of showmanship is to hop hastily from foot to foot with his hand in the air, like someone needing to be excused from class in a hurry, is having the time of his life.

The day after the show, the band are due to have their photograph taken for this magazine. But Gore and Fletcher have spent the night partying and only Gahan shows up, looking terrifyingly fit in a pair of unfeasibly tight trousers. He’s a likeable bloke; part bolshy Essex wideboy, part heart-on-sleeve recovering addict. “I don’t know why the boy’s didn’t want to do this,” he says. “They wanted to hit [notorious drinking / gambling area] The Strip.”

Gahan was in bed by midnight, with his Sigur Rós CD, copy of Norman Mailer’s The Fight and third wife, Jennifer. “As if they’ll look any better in Chicago!” he scoffs.

Blame their Basildon roots, early years as electro-pop contemporaries of Blancmange or Gore’s penchant for dressing in mail-order perv-wear; but there remains a nagging sense that Depeche Mode don’t always get their due. Apart from The Rolling Stones, they’ve been Britain’s biggest musical export for over a decade. They were the first alternative group to play US stadiums: in 1990, an in-store signing at Los Angeles’ Wherehouse Records was shut down by 200 police, including helicopters and mounted officers in riot gear, after 17,000 fans got restless. That they’re still with us is remarkable enough. Depeche Mode aren’t the only group whose singer has “died” from a heroin overdose but they are the only one still performing with him today. Last time they toured on this scale in the mid-‘90s, a combination of 15 months on the road plus a bottomless appetite for narcotics equalled catastrophe for all concerned.

In New Orleans, Gahan attempted to perform an encore while suffering a heart attack. In LA, Gore endured a band meeting while spread-eagled on the floor, paralysed with seizures. In Honolulu, Fletcher was hospitalised with a nervous breakdown, telling staff at The Priory that Gahan was the devil. Back then, Gahan was spending $3000 a week on drugs: the same amount the band deemed necessary to employ an on-tour shrink.

Then things really started getting out of hand. Back home in LA, Gahan’s self-destructive lifestyle escalated. When he wasn’t wandering around with a .38 revolver tucked into his underpants, he was spending 12 hours a day inside his wardrobe, watching the weather channel in the company of The Tin Man, a doll he was convinced could talk. Rehab and attempted suicide followed in 1995, before Gahan OD’d at the Sunset Marquis Hotel the next year, dying for two minutes, before paramedics saved him. Eventually he entered a “sober living house” in LA. He hasn’t drunk or done drugs since 6 June 1996.

Today, Gahan gets his kicks running, for times a week. The singer lives in New York’s West Village, Fletcher in London’s Maida Vale, and Gore in Santa Barbara. Geography isn’t the only thing separating them. They will only be interviewed individually; over the years, all three have used the press to vent frustrations they’re seemingly unable to voice to each other. Notably, Gahan has complained that Gore wasn’t there for him when he overdosed, and that, as the singer of Gore’s lyrics, he’s always seeking his approval.

“I’m very angry with Martin,” he said in 2003. “I’d never ask him, Hey, Mart, couldn’t we do this song part in another way? I know what his answer would be. Unless he’s open to both me and him coming into the studio with songs, I don’t see there’s a point in carrying on.”

Gahan released a successful solo album, Paper Monsters, that same year, and Playing The Angel is the first Depeche Mode collection to feature his writing (one of his songs, Suffer Well, is their next single). At an initial band meeting Gahan demanded half the album. Gore offered two or three songs. They eventually settled on three (“It was a bit weird,” observes Fletcher, “because Dave had 17 songs and Martin only had four at that time.”)

Gahan has found new stability through his family. He’s just packed eldest son Jack off to music school, something he says brought a tear to his eye. “I told him it’s only the lawyers who make the real money,” he grins. His new health regime – “Drink lots of water. Run. Try not to stress; you can’t change anything” seems to suit him. “People associate doom and gloom with drug addiction and alcohol abuse,” he says. “And there was a deep self-hatred there. But once you start to accept these things, you can actually move forward.”

The Windy City is Depeche Mode’s next stop, somewhere that lives up to its name as a storm causes hair-raising turbulence aboard the band’s 25-seat private aircraft. “The stewardess was going down the aisle on her hands and knees. It was like Almost Famous,” says Fletcher, referring to the film in which fictional band Stillwater fear their aircraft’s doomed, and their drummer seizes the moment to announce he’s gay. “Except Martin shouted, I’m not gay!” (Gore once complained that people wrongly assumed the group were homosexuals, a conclusion you sense reached largely on the basis of his own wardrobe.)

Next morning Fletcher meets me for coffee. With his Prada Sport trousers, Julian Sands hairdo and financial newspaper tucked under one arm, he’s the least convincing of rock stars. Fletcher’s role in the band has been the subject of some teasing: “Fletch” often being regarded as “the other one”.

“You’ve got the transvestite songwriter, the tattooed frontman and I represent the man in the street, I suppose.”

He’s still on medication following his breakdown, something he reasons he was predisposed to (his father has obsessive-compulsive disorder) and explains that this time around, the band are taking it easy. “I think recreational drugs at the right time can be good fun,” he says. “Now we’re trying to pace ourselves a bit. I sound like a football manager.”

Does he still enjoy touring?

“No,” he says, firmly. “Martin and I were both dreading this tour. America is a very hard place to tour. There’s shopping malls and that’s it. Europe’s a bit more interesting.

Closer to home, where the architecture is more to his liking, Fletcher is wont to organise “Fletch’s Tours”, inviting anyone in Depeche Mode’s touring party to meet him in hotel reception each morning, where he’ll guide them on walks of historical interest.

Gore is “my best friend… well, one of my best friends”, whereas Gahan is “more like a brother to me”. “You don’t want to see your brother every day. It’s more of a love thing.”

[Q, Febuary 2006. Words: Johnny Davis. Pictures: Ross Halfin.]

Engaging article following the band on tour in the USA. It covers the usual Playing The Angel material - ie the band surmounting their dysfunctions and Dave being allowed to write some songs - but the many personal glimpses of each band member makes it a worthwhile read.

" Fifty million albums’ worth of “pain and suffering in various tempos” – as Playing The Angel’s back cover has it – have made Depeche Mode wealthy men. “Dave says I’ve made a 25-year career out of one subject,” says Gore, when I meet him backstage later that day. “That’s wrong. It’s two.” "

SHOWTIME!

Dave Gahan looks wrecked. Slack of jaw and boggly of eye, he leers upwards. His polka-dot shirt is adrift at nipple-height. His cheeks are hollow, his hair lank and nasty. Years of injecting heroin and cocaine have done him in.

“He didn’t look great, did he?” says Tony Sanchez.

“Now he’s incredibly hot,” says Lisa Andrews. “Have you seen him dance? He’s awesome.”

The singer’s once-sickly features peer out from a framed gold disc for Depeche Mode’s 1993 album Songs Of Faith And Devotion, the never-ending tour which resulted in breakdowns, hospitalisations and overdoses. Today, of course, Gahan couldn’t look healthier. But then, plenty’s changed.

Tony and Lisa are waiting to see the band in Las Vegas’ Hard Rock Hotel, a shrine to the more colourful aspects of rock’n’roll history. Along with several hundred other Depeche Mode fans, they’ve been here all day.

Later it will become obvious why, after 25 years and 11 albums, Depeche Mode can sell out tour dates like this in 48 seconds. Live, they practically blow the doors off, dispatching a song, such as 1981’s Just Can’t Get Enough, with the vim of a brand new tune. Gahan is perhaps rock’s last great frontman; disarming the band’s more gothic moments by hollering “Sing it!”, “Come on!”, and “Yeah, that’s right!” any number of times. Gore, wearing leather bum-flap, feathery angel wings and a Mohican-shaped hat, vamps it up on a star-shaped guitar. Even keyboardist Andrew Fletcher, whose definition of showmanship is to hop hastily from foot to foot with his hand in the air, like someone needing to be excused from class in a hurry, is having the time of his life.

The day after the show, the band are due to have their photograph taken for this magazine. But Gore and Fletcher have spent the night partying and only Gahan shows up, looking terrifyingly fit in a pair of unfeasibly tight trousers. He’s a likeable bloke; part bolshy Essex wideboy, part heart-on-sleeve recovering addict. “I don’t know why the boy’s didn’t want to do this,” he says. “They wanted to hit [notorious drinking / gambling area] The Strip.”

Gahan was in bed by midnight, with his Sigur Rós CD, copy of Norman Mailer’s The Fight and third wife, Jennifer. “As if they’ll look any better in Chicago!” he scoffs.

Blame their Basildon roots, early years as electro-pop contemporaries of Blancmange or Gore’s penchant for dressing in mail-order perv-wear; but there remains a nagging sense that Depeche Mode don’t always get their due. Apart from The Rolling Stones, they’ve been Britain’s biggest musical export for over a decade. They were the first alternative group to play US stadiums: in 1990, an in-store signing at Los Angeles’ Wherehouse Records was shut down by 200 police, including helicopters and mounted officers in riot gear, after 17,000 fans got restless. That they’re still with us is remarkable enough. Depeche Mode aren’t the only group whose singer has “died” from a heroin overdose but they are the only one still performing with him today. Last time they toured on this scale in the mid-‘90s, a combination of 15 months on the road plus a bottomless appetite for narcotics equalled catastrophe for all concerned.

In New Orleans, Gahan attempted to perform an encore while suffering a heart attack. In LA, Gore endured a band meeting while spread-eagled on the floor, paralysed with seizures. In Honolulu, Fletcher was hospitalised with a nervous breakdown, telling staff at The Priory that Gahan was the devil. Back then, Gahan was spending $3000 a week on drugs: the same amount the band deemed necessary to employ an on-tour shrink.

Then things really started getting out of hand. Back home in LA, Gahan’s self-destructive lifestyle escalated. When he wasn’t wandering around with a .38 revolver tucked into his underpants, he was spending 12 hours a day inside his wardrobe, watching the weather channel in the company of The Tin Man, a doll he was convinced could talk. Rehab and attempted suicide followed in 1995, before Gahan OD’d at the Sunset Marquis Hotel the next year, dying for two minutes, before paramedics saved him. Eventually he entered a “sober living house” in LA. He hasn’t drunk or done drugs since 6 June 1996.

Today, Gahan gets his kicks running, for times a week. The singer lives in New York’s West Village, Fletcher in London’s Maida Vale, and Gore in Santa Barbara. Geography isn’t the only thing separating them. They will only be interviewed individually; over the years, all three have used the press to vent frustrations they’re seemingly unable to voice to each other. Notably, Gahan has complained that Gore wasn’t there for him when he overdosed, and that, as the singer of Gore’s lyrics, he’s always seeking his approval.

“I’m very angry with Martin,” he said in 2003. “I’d never ask him, Hey, Mart, couldn’t we do this song part in another way? I know what his answer would be. Unless he’s open to both me and him coming into the studio with songs, I don’t see there’s a point in carrying on.”

Gahan released a successful solo album, Paper Monsters, that same year, and Playing The Angel is the first Depeche Mode collection to feature his writing (one of his songs, Suffer Well, is their next single). At an initial band meeting Gahan demanded half the album. Gore offered two or three songs. They eventually settled on three (“It was a bit weird,” observes Fletcher, “because Dave had 17 songs and Martin only had four at that time.”)

Gahan has found new stability through his family. He’s just packed eldest son Jack off to music school, something he says brought a tear to his eye. “I told him it’s only the lawyers who make the real money,” he grins. His new health regime – “Drink lots of water. Run. Try not to stress; you can’t change anything” seems to suit him. “People associate doom and gloom with drug addiction and alcohol abuse,” he says. “And there was a deep self-hatred there. But once you start to accept these things, you can actually move forward.”

The Windy City is Depeche Mode’s next stop, somewhere that lives up to its name as a storm causes hair-raising turbulence aboard the band’s 25-seat private aircraft. “The stewardess was going down the aisle on her hands and knees. It was like Almost Famous,” says Fletcher, referring to the film in which fictional band Stillwater fear their aircraft’s doomed, and their drummer seizes the moment to announce he’s gay. “Except Martin shouted, I’m not gay!” (Gore once complained that people wrongly assumed the group were homosexuals, a conclusion you sense reached largely on the basis of his own wardrobe.)

Next morning Fletcher meets me for coffee. With his Prada Sport trousers, Julian Sands hairdo and financial newspaper tucked under one arm, he’s the least convincing of rock stars. Fletcher’s role in the band has been the subject of some teasing: “Fletch” often being regarded as “the other one”.

“You’ve got the transvestite songwriter, the tattooed frontman and I represent the man in the street, I suppose.”

He’s still on medication following his breakdown, something he reasons he was predisposed to (his father has obsessive-compulsive disorder) and explains that this time around, the band are taking it easy. “I think recreational drugs at the right time can be good fun,” he says. “Now we’re trying to pace ourselves a bit. I sound like a football manager.”

Does he still enjoy touring?

“No,” he says, firmly. “Martin and I were both dreading this tour. America is a very hard place to tour. There’s shopping malls and that’s it. Europe’s a bit more interesting.

Closer to home, where the architecture is more to his liking, Fletcher is wont to organise “Fletch’s Tours”, inviting anyone in Depeche Mode’s touring party to meet him in hotel reception each morning, where he’ll guide them on walks of historical interest.

Gore is “my best friend… well, one of my best friends”, whereas Gahan is “more like a brother to me”. “You don’t want to see your brother every day. It’s more of a love thing.”

Last edited: