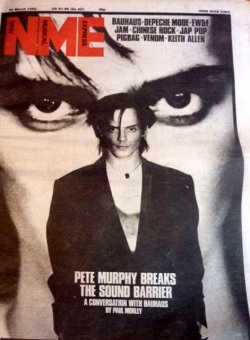

Sound Of The Suburbs

[NME, 20th March 1982. Words: Lynn Hanna. Pictures: Peter Anderson.]

SOUND OF THE SUBURBS

Apart from his clothes, which are meticulously modish, Martin Gore’s baby blond curls, bashful expression and sweet smile make him look like the boy in Bubbles, Millais’ famous Victoria advert for Pears soap.

His group mate Andrew Fletcher looks comparatively harsh by Depeche pop standards: sandy hair sticks up straight from his head and his manner, although chatty, tends towards dry. It’s dark Dave Gahan, the singer with the soft face and sunny smile, who opens the door of his parents’ semi-detached house in the satellite suburb of Basildon.

There seems to be something in the air which encourages clear complexions, wholesome electro-pop, clean-cut teen culture and untroubled eyes.

The taxi from the station bowls along wide, smooth roads between low, grey rows of modern estate housing, past broad sweeps of spring green. On the surface it’s a closed world of comforting order, easy affluence, unchallenged conformity and modest domesticity. Depeche Mode – a little flushed from the drowsy afternoon combination of sunshine, central heating and a flaring fire – sit in the small, square cosy living room of a house identical to the ones they all share with their respective parents.

A bright, neat girl sits at one end of the settee, quietly flicking through a magazine. [1] Dave Gahan makes coffee, although he drinks hot chocolate himself. Audible through wafer thin walls, now nearer, now farther, come the thin tones of Dave’s younger brother, a squatter, pudgier version of Dave himself, as he wanders through the house with his small Casio keyboard.

“He usually plays it in the loo,” says Dave, “because it’s got good reverb in there.”

All over Basildon, Andrew tells me, young synthesizer bands are starting up, despite the lack of rehearsal rooms or places to play. For Depeche Mode who smile and reminisce their way through an afternoon at home, it doesn’t seem so long ago that they were playing house-gigs themselves to a small audience in pyjamas with additional soft toys and teddy-bears.

Time has flown, they think, since they caught the commuter train to the bank, the insurance office and college every morning. Because Depeche Mode signed to an independent label for no advance, they were still doing day jobs when “New Life” was at Number 20 in the charts, and a week after they finished work they were on TOTP. Four months ago Andrew Fletcher had never flown, now he finds air travel no more or less exciting than catching the 7 o’clock train into town.

This is the first day of Depeche Mode have had in months, sandwiched between a trip to Spain and a spell in the studio. And although they were looking forward to an uninterrupted reunion with old friends and family, they’ve amiably agreed to one more interview.

Depeche Mode are just too nice to say no. [2]

“Every day there seems to be something,” says Dave resignedly. “Up until a certain point you get used to it. But you do begin to wonder what good it actually does.”

Does being nice come naturally?

“Not any more it doesn’t,” says Andrew whose irony is in counterpoint to Dave’s ready chatter and Martin’s shy, attentive silence (“He’s got a lot to say, but he never says it,” explains Andrew. “He’s not very good at interviews.”)

“You’re thrown into something and you act naturally and that’s what comes out. Then you’re known as being nice and cute all the time; and when you’ve been touring for three months, you just want to explode. But when you’re surrounded by nice people who are so friendly, you trust them. If they say something it’s hard to say, no. Dan (Daniel Miller of Mute) has done so much for us, you can’t get stroppy with him. All the people in the office really work hard for us, you can’t upset them. The main thing is, we’ve been so lucky, you feel, why should we be arguing? We’ve got somewhere and we should work.”

Depeche Mode aren’t a rock and roll band, they tell me, and they don’t enjoy the traditional tour trappings. At their Hammersmith Odeon concerts, which they filled twice in a fortnight, their show was remarkable for its fetching simplicity and lack of spectacle, its narrowing of distance and rejection of elitism, its guileless involvement and unselfconscious innocence.

Yet here they are between tour and LP, still bubbly but worrying a little about becoming blasé over continents and countries, jets and helicopters, video and TV. Dave Gahan’s got a swelling stye on one eye from infected water in a Spanish shower.

“If I’m wearing sunglasses in the pictures, you’ll have to explain it wasn’t trying to be cool, I’m embarrassed about my eye.”

Is there any way in which they can avoid stepping into the spiralling restrictive trap of success?

“We don’t want anything,” says Andrew. “We just carry on from day to day. We haven’t got any ambitions. Our ambition is to buy a house or something like that.”

“Obviously to be more successful would be a good thing,” adds Dave. “Or to just stay as we are now and keep releasing good material.”

“Things don’t happen so fast that you don’t really know what’s going to happen,” says Martin softly.

“To go back now would be really hard,” Andrew continues. “There’s so many people we have to pay. It’s the album-tour-album-tour trap that’s the worst thing. That’s why Vince (Clarke) left, he probably felt that he was getting trapped because that’s what he saw in front of him. He looked at it with a bigger scope than we did, I think. He looked ahead more.

“The only point of bitterness really is the fact that we’re really working hard and promoting his material and he’s doing what we want to do but can’t.

“Vince has got all the time in the world now,” adds Dave. “He’s done a few adverts, a few jingles. Peter Powell’s got a new programme out and he wrote the theme tune for that. We were offered a Tizer advert but we just couldn’t do it. It would be really good if we had the time to do things like that, just look at it in a bigger way, different ways of earning money.”

Far from falling flat on their fresh faces, as some feared they would do when primary writer Clarke left, Depeche Mode have recruited new member Alan Wilder (not present today since he’s only temporary), and gathered new strength since “See You” has taken its proper place in the most exhilarating chart for months.

Why do they think people relate to them so well?

“I suppose it’s because they see us as the boy next door,” says Dave.

“The blokes see us like lads, electronic versions of The Angelic Upstarts,” adds Andrew. “You get those sort of people outside the dressing room door going Oi Andy. You have to speak to them in your best Cockney accent. You go, Yer, alright, ’ang on. You get the little girls that you have to be really nice to because they’re like your little sister.”

[NME, 20th March 1982. Words: Lynn Hanna. Pictures: Peter Anderson.]

Sympathetic and intelligent interview of the band (minus Alan) at the time of the release of "See You". The innocence is plain to see without being harped on about, and looks at how the band intend to hang on to success without falling into routine or being dismissed as too lightweight. Very wise in hindsight, and the rose tinted description of Basildon will have you all misty-eyed.

" This is the first day of Depeche Mode have had in months, sandwiched between a trip to Spain and a spell in the studio. And although they were looking forward to an uninterrupted reunion with old friends and family, they’ve amiably agreed to one more interview.

Depeche Mode are just too nice to say no. "

Summary: Sympathetic and intelligent interview of the band (minus Alan) at the time of the release of "See You". The innocence is plain to see without being harped on about, and looks at how the band intend to hang on to success without falling into routine or being dismissed as too lightweight. Very wise in hindsight, and the rose tinted description of Basildon will have you all misty-eyed. [1837 words]

SOUND OF THE SUBURBS

Apart from his clothes, which are meticulously modish, Martin Gore’s baby blond curls, bashful expression and sweet smile make him look like the boy in Bubbles, Millais’ famous Victoria advert for Pears soap.

His group mate Andrew Fletcher looks comparatively harsh by Depeche pop standards: sandy hair sticks up straight from his head and his manner, although chatty, tends towards dry. It’s dark Dave Gahan, the singer with the soft face and sunny smile, who opens the door of his parents’ semi-detached house in the satellite suburb of Basildon.

There seems to be something in the air which encourages clear complexions, wholesome electro-pop, clean-cut teen culture and untroubled eyes.

The taxi from the station bowls along wide, smooth roads between low, grey rows of modern estate housing, past broad sweeps of spring green. On the surface it’s a closed world of comforting order, easy affluence, unchallenged conformity and modest domesticity. Depeche Mode – a little flushed from the drowsy afternoon combination of sunshine, central heating and a flaring fire – sit in the small, square cosy living room of a house identical to the ones they all share with their respective parents.

A bright, neat girl sits at one end of the settee, quietly flicking through a magazine. [1] Dave Gahan makes coffee, although he drinks hot chocolate himself. Audible through wafer thin walls, now nearer, now farther, come the thin tones of Dave’s younger brother, a squatter, pudgier version of Dave himself, as he wanders through the house with his small Casio keyboard.

“He usually plays it in the loo,” says Dave, “because it’s got good reverb in there.”

All over Basildon, Andrew tells me, young synthesizer bands are starting up, despite the lack of rehearsal rooms or places to play. For Depeche Mode who smile and reminisce their way through an afternoon at home, it doesn’t seem so long ago that they were playing house-gigs themselves to a small audience in pyjamas with additional soft toys and teddy-bears.

Time has flown, they think, since they caught the commuter train to the bank, the insurance office and college every morning. Because Depeche Mode signed to an independent label for no advance, they were still doing day jobs when “New Life” was at Number 20 in the charts, and a week after they finished work they were on TOTP. Four months ago Andrew Fletcher had never flown, now he finds air travel no more or less exciting than catching the 7 o’clock train into town.

This is the first day of Depeche Mode have had in months, sandwiched between a trip to Spain and a spell in the studio. And although they were looking forward to an uninterrupted reunion with old friends and family, they’ve amiably agreed to one more interview.

Depeche Mode are just too nice to say no. [2]

“Every day there seems to be something,” says Dave resignedly. “Up until a certain point you get used to it. But you do begin to wonder what good it actually does.”

Does being nice come naturally?

“Not any more it doesn’t,” says Andrew whose irony is in counterpoint to Dave’s ready chatter and Martin’s shy, attentive silence (“He’s got a lot to say, but he never says it,” explains Andrew. “He’s not very good at interviews.”)

“You’re thrown into something and you act naturally and that’s what comes out. Then you’re known as being nice and cute all the time; and when you’ve been touring for three months, you just want to explode. But when you’re surrounded by nice people who are so friendly, you trust them. If they say something it’s hard to say, no. Dan (Daniel Miller of Mute) has done so much for us, you can’t get stroppy with him. All the people in the office really work hard for us, you can’t upset them. The main thing is, we’ve been so lucky, you feel, why should we be arguing? We’ve got somewhere and we should work.”

Depeche Mode aren’t a rock and roll band, they tell me, and they don’t enjoy the traditional tour trappings. At their Hammersmith Odeon concerts, which they filled twice in a fortnight, their show was remarkable for its fetching simplicity and lack of spectacle, its narrowing of distance and rejection of elitism, its guileless involvement and unselfconscious innocence.

Yet here they are between tour and LP, still bubbly but worrying a little about becoming blasé over continents and countries, jets and helicopters, video and TV. Dave Gahan’s got a swelling stye on one eye from infected water in a Spanish shower.

“If I’m wearing sunglasses in the pictures, you’ll have to explain it wasn’t trying to be cool, I’m embarrassed about my eye.”

Is there any way in which they can avoid stepping into the spiralling restrictive trap of success?

“We don’t want anything,” says Andrew. “We just carry on from day to day. We haven’t got any ambitions. Our ambition is to buy a house or something like that.”

“Obviously to be more successful would be a good thing,” adds Dave. “Or to just stay as we are now and keep releasing good material.”

“Things don’t happen so fast that you don’t really know what’s going to happen,” says Martin softly.

“To go back now would be really hard,” Andrew continues. “There’s so many people we have to pay. It’s the album-tour-album-tour trap that’s the worst thing. That’s why Vince (Clarke) left, he probably felt that he was getting trapped because that’s what he saw in front of him. He looked at it with a bigger scope than we did, I think. He looked ahead more.

“The only point of bitterness really is the fact that we’re really working hard and promoting his material and he’s doing what we want to do but can’t.

“Vince has got all the time in the world now,” adds Dave. “He’s done a few adverts, a few jingles. Peter Powell’s got a new programme out and he wrote the theme tune for that. We were offered a Tizer advert but we just couldn’t do it. It would be really good if we had the time to do things like that, just look at it in a bigger way, different ways of earning money.”

Far from falling flat on their fresh faces, as some feared they would do when primary writer Clarke left, Depeche Mode have recruited new member Alan Wilder (not present today since he’s only temporary), and gathered new strength since “See You” has taken its proper place in the most exhilarating chart for months.

Why do they think people relate to them so well?

“I suppose it’s because they see us as the boy next door,” says Dave.

“The blokes see us like lads, electronic versions of The Angelic Upstarts,” adds Andrew. “You get those sort of people outside the dressing room door going Oi Andy. You have to speak to them in your best Cockney accent. You go, Yer, alright, ’ang on. You get the little girls that you have to be really nice to because they’re like your little sister.”