You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Depeche Mode Staying Mute (The Face, 1990)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1990 staying mute the face

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,494

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

" Along with The Cure and New Order, their success here is based on their massive appeal to young Americans expressing a controlled rebellion. It's nothing to do with flag burning and spying for the Commies; it's more to do with wearing black in strange approximations of every white British youth cult since punk. "

Unusual article, describing Mute via the diverse lives of four of its bands. Consequently most of the article is not about Depeche Mode, but the article contrasts their big-league American success with the mixed achievements of other bands and paints a compelling broader picture. Seeing Depeche this way is a healthy corrective to anyone leaning too far towards imagining them as misunderstood outsiders. A bit on the fringe for Sacred DM, but fascinating nonetheless.

Electronic. Teutonic. Independent. European. Regardless of the reality of its catalogue, Mute Records has a certain image. Like any record label with a desire to survive and a vested interest in the truth, Mute, a British independent established in 1978, denies any image. But it's there. Even at its poppiest with Erasure, it maintains an intellectual air. It has a lot to do with the artwork; a great deal to do with its perceived independent integrity, and everything to do with the long shadows thrown by performance artist Diamanda Galas and musicians such as Nick Cave and Wire. Serious people.

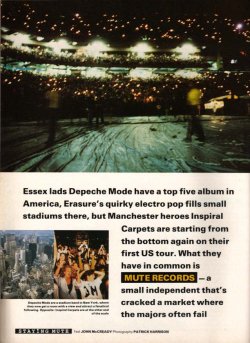

Aware of the pitfalls of such pigeonholing, there are some Mute artists who are doing their level best to upturn the clichés. Take Douglas McCarthy of famed serious young men Nitzer Ebb, who are supporting Depeche Mode on their current US tour. Douglas was introduced to Bono of U2, a guest at Depeche's 40,000-plus New York stadium date. Douglas likes a drink or three. He insisted on referring to the rock pope as 'Bongo'. Bongo tells him he puts him in mind of a young Jerry Lee Lewis, and it's true that Douglas could probably give the piano-thumping hellraiser a good run for his money.

High above the crowd in a press box at the Giants stadium, he shakes a half-empty vodka bottle in the general direction of anyone he wants to talk to. Douglas is being what he later refers to as a "Turbo Bastard". "The Mode are Turbo Bastards as well. Maybe it's something to do with us all coming from Essex." Having just duped the assembled crowd of teenage Anglophiles into thinking he is an English industrial fetishist onstage, he hangs out of the window taunting the other support band The Jesus And Mary Chain with shouts of "Rock, Rock!". Of course they can't hear him, so he decides to try and capture their attention by climbing through the window of the box into the next one. In the course of his fumbling acrobatics he almost kills himself.

Similarly concerned with Mute misconceptions, Depeche Mode's singer Dave Gahan falls into the dressing room of new label-mates Inspiral Carpets after their first New York show. Pushing through the assembled label bosses keen to bag the group still shopping for an American contract, he drunkenly tells the Inspirals he can drink them under the table and stumbles around like Sid Vicious used to pretend to. The Manchester independent heroes are concerned with neither the record executives ready to talk dollars or drinking challenges from moody electronic pop groups. "Let's go out to a fucking club," says bass player Martyn Walsh, known to his friends as Bungle due to his apparent similarity to the children's TV puppet of the same name. "This is our first night in New York. Let's get cracking!"

Mute Records, having started out as a one-man, one-room operation in the late Seventies, reaches its twelfth year with America on its mind. US success has made its transatlantic operation a priority. Depeche Mode have a new album, "Violator", which has bobbed up and down the country's top five since its release. Erasure are doing a swift second round of 20,000-plus stadiums in less than a year. The interest both from US record labels and young American record buyers hooked by some romantic notion of electronic Englishness has almost begun to overshadow a European operation responsible for a uniquely oblique back catalogue. The label's founder and owner, Daniel Miller, is here to oversee the setting up of Mute America and watch the legal ping pong as Depeche Mode negotiate a new megabuck deal.

All of this may be surprising to those who associate Mute with Mark Stewart, Laibach or even Daniel himself. He provided the label with its first release: "TVOD" and "Warm Leatherette" (later covered by Grace Jones) were among the first minimalist synthesised pop songs. This proto-techno double A-sided single has much to do with the image the label still has. Its success with Depeche Mode and Erasure in any area of the world is hard to ignore, but unassuming synth innovator Daniel Miller as King of America? Dave Gahan as a stadium rival to Mick Jagger? Mute's success in the big country and the fact that Depeche Mode have a bodyguard each when they can probably walk down Basildon High Street in relative peace might make you sit up and listen. In America, Mute is all stretch limousines and big business.

What may surprise you more is that Mute America is as much to do with lads on the piss than the angst-ridden soundscapes that American Dance Orientated Rock radio has turned into a Depeche-led phenomenon. DOR, as it has come to be known, appeals to teenagers who refuse to subscribe to the American Dream; who would rather listen to New Order, The Cure and Nitzer Ebb than Bon Jovi or Bruce Springsteen.

Though a few days later, he'll be pissed up explaining his schizophrenic "Ron Dali" personality ("part arty bastard, part pisshead"), Depeche Mode's Alan Wilder is for the moment happy to chew on the odd grape and talk about the band quietly and carefully. The ever amiable Fletch joins him in a sumptuous hotel suite with a bird's eye view of Manhattan which illustrates just how far they have come. Both are keen to establish the fact that it has taken them ten years of touring to get such a good view of New York City. "We played the real shitholes here," says Fletch. "But we kept coming back and we'd keep doubling the crowds."

Along with The Cure and New Order, their success here is based on their massive appeal to young Americans expressing a controlled rebellion. It's nothing to do with flag burning and spying for the Commies; it's more to do with wearing black in strange approximations of every white British youth cult since punk. At the Giants stadium concert two days later, I meet my first goth-mod.

Depeche Mode are DOR heroes treated with the same degree of seriousness as New Order. They've managed to maintain the cult image crucial to DOR support. These kids in Doc Marten boots and fishtail parkas want the group to stay a high-school secret. Depeche Mode have to be careful. Major tour sponsorship is a real prospect for an act who will have played to over half a million people inside the next three months. "But we can't perform in front of a Pepsi logo," says Alan. "If they gave us a million dollars the only thing we'd let them do is put their name on the back of the ticket."

At the Giants stadium I get through the gate with a ticket advertising no particular soft drink. The huge scale of the event itself is breathtaking. It doesn't really matter what Depeche Mode are like.

The delicate edges of the songs on the current "Violator" album are roughed up for mass consumption, and while the others remain behind their keyboards for most of the performance, Dave Gahan activates the crowd with a display of rock showmanship only Roger Daltry could match. But Martin Gore's sensitively pervy songwriting survives, and for those in doubt as to where the group's heart lies, a middle section of songs drops to a whisper with a monochrome film show from photographer Anton Corbijn. The young crowd is silent for a while. It seems to sum up what Daniel Miller later tells me about how most people in the business seriously underestimate the artistic and intellectual capacities of young record buyers. "I've always opposed that idea." The film show over, the screaming starts again when Dave begins to rotate his pelvis like the big E. The group's appeal remains a complex issue.

At the other end of Mute's electronic rock and roll telescope, the end where everything looks smaller, Inspiral Carpets are sitting on sports bags full of expensive T-shirts outside their New York hotel. It's eight in the morning. "Where's the fucking van? " asks Craig. The group are back on the pavement without the luxury coaches and private tour caterers they are used to in Europe. The mooing audiences - a display of surreal mindlessness inspired by their UK Cow label - are also missing. The Inspirals are ten years behind Depeche Mode. But with their famed love of organisation, a business sense that has ensured that those who want to have bought their own houses, and a commitment that is almost frightening, it will probably take them only two years to catch up. The group are travelling to Boston to play, having knocked spots off New York last night with a show that came over loud and clear.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,494

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

There is a confidence that comes from a year of playing to more than appreciative crowds in Britain. In Britain they probably get bigger vans too. In order to accommodate myself and photographer Patrick Harrison for a swift life-on-the-road travelogue, another van must be rented. When Craig has finished taking the piss out of my Scouse accent, we check the fruits of each other's NY vinyl junkie hunt. We get talking about, well, life and all things moo. I decide to pass up the opportunity of exhibiting my killer Manc accent when I see he's purchased a 12-inch copy of McFadden and Whitehead's Philly classic "Ain't No Stoppin' Us Now". I frighten them instead with an opening question which almost has them stop the van and let me out. What do you think of The Stone Roses? "For a minute there, I thought you were a goon," says Graham, expecting the usual barrage of Manchester phenomenon questions. When I tell them I'm taking the piss, they relax.

As Mute's most recent addition and the label's first signing for two years, Inspiral Carpets seem perhaps the most unlikely band in Britain to end up as part of Daniel Miller's drink-crazed rock'n'roll circus. First, because they appeared to be doing very well with their own Manchester-based Cow label, selling records and T-shirts by the cartload, and second, because Clint Boon's organ frenzy - the Inspiral's musical trademark, is as perversely electronic as it's possible to get.

"We just found we couldn't go any further on our own," says Craig. "The single 'Move' proved that to us." The group initially went to Daniel Miller for advice. He started the conversation with, "So you're thinking of throwing it all away." Daniel later confirms this: "I think it's important for labels like Cow to be seen to be making it work in the independent sector. Otherwise it all falls apart and the independents just become a stepping stone again." The group left him a tape of their then unreleased album. The rest could soon become independent history. The Inspirals are now committed to Mute, but still have their own office in Manchester. "Nothing's really changed," says singer Tom Hinglely. "Cow still exists, it just means we can spend less time worrying about how many copies of the single this shop or that shop have and more about the music."

At this stage Graham and Clint, having made the most of the previous evening's after-show fun and games, begin to doze off. Craig is 19. He refers to them as "The Old Bastards". His reasons for getting involved with Mute are slightly different. "The day we signed you should have seen the back catalogue stuff we came out with. Loads of good tunes."

The signing did not include the Cow merchandising empire, a lucrative T-shirt sideline which stays in their hands. In America, however, long-sleeve success stories mean nothing. Anyone walking about in a shirt with a cursing psychedelic cow on the front is likely to be mistaken for a deranged dairy farmer. The Inspirals are in search of an American deal and this low-key tour is a way of putting the goods in the shop window.

In Boston's Axis club the crowd is small, maybe swelling to 150 people by the end of a rousing set. The Inspiral's commitment to partying and their late-night clubbing session in New York doesn't seem to have affected them at all.

I stand at the back of the club and try to start of the ceremonial mooing cult in Boston. Nobody responds. Still, these are early days. The bovine insanity of UK shows seems like a distant memory. The Inspiral Carpets are back on the first rung. America, they believe, might be a hard one. "They still wear leather trousers here, so they might not understand," says Martyn.

The victim of a typically gruelling Mute rock'n'roll schedule, I start to flag: now I know how Robert Palmer must have felt. It's Saturday so it must be San Francisco. Erasure are playing a massive stadium full of clean-cut Americans who like a hot dog and a large Pepsi with their classic pop. The music is loud, like hi-NRG with decent tunes. Vince Clarke stands stock still behind his synth holding on to that last vestige of Mutism: the electronic keyboard. Andy Bell tries to further the rock rebellion by riding across the stage on an inflatable snail. His manner is sexual, but the snail doesn't look too uncomfortable.

Explosion after explosion flashes before us. Erasure compensate for their lack of numbers with an inspired pantomime complete with dancers and bees which hover above giant mushrooms. Andy plays the fairy godmother, camping it up like Danny La Rue with better legs. Vince is the unhappy prince stood stock still like a manic depressive who doesn't get the joke. This concert is planned to coincide with San Francisco's Festival For Freedom Of Expression organised by the local gay community. Andy offsets the frivolousness of the show by expressing his support for the event, at which he is to be one of the speakers.

Before the show, in a hotel with a view of the San Francisco skyline that isn't quite as good as Depeche Mode's view of New York but better than the Inspiral Carpets' ground floor view of Boston, I ask him what he intends to say. "Oh, I guess I'll just talk about what it's like to travel and experience homophobia on a worldwide scale." His forthright expression of his own sexuality in a world where such an attitude can cut back record sales is almost odd. But then Andy Bell, whose heroines include Debbie Harry and Madonna (he introduces one live song with the opening line from 'Vogue'), isn't one for hiding in the closets.

"You still get psychos in the audience who come out with this real queer-hating thing. I just seek them and waggle my arse in their direction." With American audiences, homophobia hasn't really been a problem. "They see the show so differently. They're used to Disneyland and the biggest thrill you can get for your money. They seem to connect with the theatrical side of it."

At this show, just like all the others, Daniel Miller has been there keeping an eye on the people he regards as "real friends as well as artists". In a rare moment of seriousness, Douglas from Nitzer Ebb refers to him as a "father figure". A label owner who prefers not to have to sign contracts (Depeche Mode and Erasure have no written contracts with Miller or Mute), few of his artists have anything negative to say about him. Mute emerges at this point as an independent family with Daniel at the head of an expensive table. He lacks the confidence you might expect, though to have achieved what he has, there's no way he can have soft-shoed through life like the good Samaritan of the record industry. Daniel, we are told, can blow his top too, like any dad.

His pre-Mute history might surprise if you expected him to be an electronics graduate who lived as an artist in Berlin until taking up the synthesiser as a more immediate tool of expression. Daniel bummed around Europe in his mid-twenties and ended up as a DJ in a club in Switzerland. "I just liked the mountains, so I decided to stay." The interview process makes him as nervous as hell. I feel cruel, like I'm watching somebody drown. He's happier talking about supporting Chelsea in the mid-Seventies than trying to pinpoint the reasons for a small UK independent's phenomenal success in America.

He began the label in 1978 in the face of general disinterest in electronic pop. "You know the way kids make lists of things they want to do when they grow up? I didn't want to be an engine driver or a fireman. I wanted to put out the kind of music nobody else liked. Of course, it's odd now that Depeche Mode are one of the most popular groups in the world." Daniel is, it seems, still there for the right reasons - still looking out for "a ridiculous noise or a great song."

"The other thing about Dan Miller," muses Nitzer Ebb's ever quotable Douglass after hanging out of another window with a paper cup on his nose, "is that I think it's well weird him signing up all these little boys with synths from Essex." Douglas's idiosyncratic geography of the label also expresses the idea that Mute is more than just boys with dark depressions and drum machines.

"There's all the guitar lot. The Aussies who sleep on the floor in the office, Nick Cave and that mob. Then there's the low-profile stuff and the re-releases; all the knob-twiddlers. Then there's the new lot, us and Renegade Soundwave. And the lolly men, the Mode and Erasure. Then he signed the Inspirals, didn't he? I thought he'd gone off his head..."

So did I until I'd met him. But the Inspirals fit snugly into the Mute masterplan - a masterplan that simply says you can make money and be in love with music at the same time. That's something some people have forgotten. "In the end," says Daniel Miller, "my reaction to a group or a piece of music is still emotional not financial."

As Mute's most recent addition and the label's first signing for two years, Inspiral Carpets seem perhaps the most unlikely band in Britain to end up as part of Daniel Miller's drink-crazed rock'n'roll circus. First, because they appeared to be doing very well with their own Manchester-based Cow label, selling records and T-shirts by the cartload, and second, because Clint Boon's organ frenzy - the Inspiral's musical trademark, is as perversely electronic as it's possible to get.

"We just found we couldn't go any further on our own," says Craig. "The single 'Move' proved that to us." The group initially went to Daniel Miller for advice. He started the conversation with, "So you're thinking of throwing it all away." Daniel later confirms this: "I think it's important for labels like Cow to be seen to be making it work in the independent sector. Otherwise it all falls apart and the independents just become a stepping stone again." The group left him a tape of their then unreleased album. The rest could soon become independent history. The Inspirals are now committed to Mute, but still have their own office in Manchester. "Nothing's really changed," says singer Tom Hinglely. "Cow still exists, it just means we can spend less time worrying about how many copies of the single this shop or that shop have and more about the music."

At this stage Graham and Clint, having made the most of the previous evening's after-show fun and games, begin to doze off. Craig is 19. He refers to them as "The Old Bastards". His reasons for getting involved with Mute are slightly different. "The day we signed you should have seen the back catalogue stuff we came out with. Loads of good tunes."

The signing did not include the Cow merchandising empire, a lucrative T-shirt sideline which stays in their hands. In America, however, long-sleeve success stories mean nothing. Anyone walking about in a shirt with a cursing psychedelic cow on the front is likely to be mistaken for a deranged dairy farmer. The Inspirals are in search of an American deal and this low-key tour is a way of putting the goods in the shop window.

In Boston's Axis club the crowd is small, maybe swelling to 150 people by the end of a rousing set. The Inspiral's commitment to partying and their late-night clubbing session in New York doesn't seem to have affected them at all.

I stand at the back of the club and try to start of the ceremonial mooing cult in Boston. Nobody responds. Still, these are early days. The bovine insanity of UK shows seems like a distant memory. The Inspiral Carpets are back on the first rung. America, they believe, might be a hard one. "They still wear leather trousers here, so they might not understand," says Martyn.

The victim of a typically gruelling Mute rock'n'roll schedule, I start to flag: now I know how Robert Palmer must have felt. It's Saturday so it must be San Francisco. Erasure are playing a massive stadium full of clean-cut Americans who like a hot dog and a large Pepsi with their classic pop. The music is loud, like hi-NRG with decent tunes. Vince Clarke stands stock still behind his synth holding on to that last vestige of Mutism: the electronic keyboard. Andy Bell tries to further the rock rebellion by riding across the stage on an inflatable snail. His manner is sexual, but the snail doesn't look too uncomfortable.

Explosion after explosion flashes before us. Erasure compensate for their lack of numbers with an inspired pantomime complete with dancers and bees which hover above giant mushrooms. Andy plays the fairy godmother, camping it up like Danny La Rue with better legs. Vince is the unhappy prince stood stock still like a manic depressive who doesn't get the joke. This concert is planned to coincide with San Francisco's Festival For Freedom Of Expression organised by the local gay community. Andy offsets the frivolousness of the show by expressing his support for the event, at which he is to be one of the speakers.

Before the show, in a hotel with a view of the San Francisco skyline that isn't quite as good as Depeche Mode's view of New York but better than the Inspiral Carpets' ground floor view of Boston, I ask him what he intends to say. "Oh, I guess I'll just talk about what it's like to travel and experience homophobia on a worldwide scale." His forthright expression of his own sexuality in a world where such an attitude can cut back record sales is almost odd. But then Andy Bell, whose heroines include Debbie Harry and Madonna (he introduces one live song with the opening line from 'Vogue'), isn't one for hiding in the closets.

"You still get psychos in the audience who come out with this real queer-hating thing. I just seek them and waggle my arse in their direction." With American audiences, homophobia hasn't really been a problem. "They see the show so differently. They're used to Disneyland and the biggest thrill you can get for your money. They seem to connect with the theatrical side of it."

At this show, just like all the others, Daniel Miller has been there keeping an eye on the people he regards as "real friends as well as artists". In a rare moment of seriousness, Douglas from Nitzer Ebb refers to him as a "father figure". A label owner who prefers not to have to sign contracts (Depeche Mode and Erasure have no written contracts with Miller or Mute), few of his artists have anything negative to say about him. Mute emerges at this point as an independent family with Daniel at the head of an expensive table. He lacks the confidence you might expect, though to have achieved what he has, there's no way he can have soft-shoed through life like the good Samaritan of the record industry. Daniel, we are told, can blow his top too, like any dad.

His pre-Mute history might surprise if you expected him to be an electronics graduate who lived as an artist in Berlin until taking up the synthesiser as a more immediate tool of expression. Daniel bummed around Europe in his mid-twenties and ended up as a DJ in a club in Switzerland. "I just liked the mountains, so I decided to stay." The interview process makes him as nervous as hell. I feel cruel, like I'm watching somebody drown. He's happier talking about supporting Chelsea in the mid-Seventies than trying to pinpoint the reasons for a small UK independent's phenomenal success in America.

He began the label in 1978 in the face of general disinterest in electronic pop. "You know the way kids make lists of things they want to do when they grow up? I didn't want to be an engine driver or a fireman. I wanted to put out the kind of music nobody else liked. Of course, it's odd now that Depeche Mode are one of the most popular groups in the world." Daniel is, it seems, still there for the right reasons - still looking out for "a ridiculous noise or a great song."

"The other thing about Dan Miller," muses Nitzer Ebb's ever quotable Douglass after hanging out of another window with a paper cup on his nose, "is that I think it's well weird him signing up all these little boys with synths from Essex." Douglas's idiosyncratic geography of the label also expresses the idea that Mute is more than just boys with dark depressions and drum machines.

"There's all the guitar lot. The Aussies who sleep on the floor in the office, Nick Cave and that mob. Then there's the low-profile stuff and the re-releases; all the knob-twiddlers. Then there's the new lot, us and Renegade Soundwave. And the lolly men, the Mode and Erasure. Then he signed the Inspirals, didn't he? I thought he'd gone off his head..."

So did I until I'd met him. But the Inspirals fit snugly into the Mute masterplan - a masterplan that simply says you can make money and be in love with music at the same time. That's something some people have forgotten. "In the end," says Daniel Miller, "my reaction to a group or a piece of music is still emotional not financial."

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,494

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

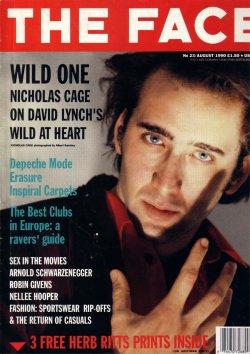

The Face

N°23

Date: August 1990

Description: Merci à Angelinda de DMTVArchives qui m'a transmis les articles correspondants

Pays: Royaume-Uni

N°23

Date: August 1990

Description: Merci à Angelinda de DMTVArchives qui m'a transmis les articles correspondants

Pays: Royaume-Uni