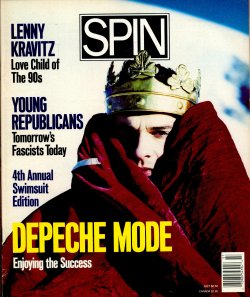

Story: Pop a La Mode

[Spin, September 28 2017, Written By Marisa Fox]

Story: Pop a La Mode

Depeche Mode may not look dangerous. They certainly don't sound dangerous. Fact is, they're not dangerous. But watch out for their fans.

The last time Depeche Mode came to the US they caused a riot. A real riot—bottles thrown, windows shaken, lots of pressing, pushing and punching. Some 20,000 fans, many of them teenaged girls, had gathered at the Warehouse in Los Angeles for an in-store appearance. Some had waited for days. Fearing for the safety of the group, security guards disbanded the affair after a scant 45 minutes.

The crowd went wild; a few had to be taken to the hospital with minor injuries. Kelly Jaffray’s mom got jabbed in the ribs, so she punched some guy in the jaw. Depeche super-fan Kelly, 15, was herself safe in the VIP section of the store. “The band all know me and they let me in without any hassles,” she boasts.

It’s true, too. In fact, when Depeche’s Andy Fletcher spotted Kelly, he gasped, “We can’t go anywhere without you.” “He was just joking,” Kelly says. “I mean they respect me because I don’t invade their space all the time. I’m not a groupie or anything. Like, I wouldn’t just sleep with them or anything. Or like, they couldn’t force me to take drugs, you know. But then, they wouldn’t. I know them and respect them and they respect me.”

In many ways, Kelly is a typical valley girl. A teenager with blue eyes and softly waved blond hair, she loves to shop on Melrose and Hollywood. She buys Quick Silver and other neon surf clothes, wears Ug boots without socks, cruises with the guys cranking KROQ on the car stereo. She says things like “Oh my gosh,” she’s getting a BMW for her Sweet Sixteen and she’d never get into a car without a box of Depeche Mode tapes.

Kelly can’t quite get through a day without listening to Depeche Mode. Her obsession has been going strong for years; it started with a single and a concert ticket. Now, 325 albums later, Kelly is one of their biggest collectors in the US, possibly the world. Her life revolves around Depeche Mode—she goes on trips to New York just to shop for Depeche paraphernalia. This year she’s hoping to go to London to get even more colored vinyl, rare remixes, posters and books. Kelly would go to any length for her fix. “If I had to I might sacrifice my life for the sake of he group,” she says, sighing.

Kelly’s mom understands. “When I was Kelly’s age I was into the Stones and drag racing. These kids aren’t as rowdy as we were, and that’s good. That’s why I encourage it. It’s a healthier habit than hanging out at the Jack in the Box and getting mixed up in a drive-by, or taking drugs and drinking.” Her mom may have bopped along to “Satisfaction,” but Kelly grooves to “Shake the Disease.” Instead of the raunchy twang of Keith Richard’s guitar, Kelly gets off on punchy rhythms programmed on synthesizers and drum machines.

Kelly was 13 when she first managed to catch a glimpse of her idols, backstage at the MTV Music Awards. “I was determined to meet them so I asked this guy who was an Aerosmith roadie to please help me. And he gave me a pass and I couldn’t believe it. There they were,” she says. “I first met their sound man, this guy named Darrel, and then I hung out with Alan Wilder. I was holding this old program from one of their shows and Martin Gore just came over and grabbed it and we started talking like we were friends.”

Kelly could go on for hours, about the time she almost had dinner with them, the time she was up at KROQ with them, about the record company bigwigs she’s met at their parties, about the 90 DM buttons she wore on her jacket for a special party, about some girl she saw leaving her hotel, all smiles and skirt half-unzipped.

“It’s strange that we appeal to so many young kids but these aren’t our only fans,” says Andy Fletcher. “We have quite a lot who are older and who have been with us since the very start, for almost 10 years.” Back in the early 80s, at the dawn of British synth-pop, Depeche Mode was more or less an underground act. As groups like Duran Duran and Human League blasted through MTV and Top 40 radio, Depeche Mode remained a faceless enigma. They were reluctant to have their picture on albums or magazines. They preferred to let their songs speak for themselves. Fronted then by Vince Clarke (who left early on to form Yaz, then Erasure), Depeche Mode were for suburban teens (Andy, Martin, Dave Gahan as lead singer and later Alan Wilder) devoted to a then-experimental instrument—the synthesizer.

“To us, it was the punk instrument,” explains the group’s songwriter Martin Gore. “It was an instant, do-it-yourself kind of tool. And because it was still new, its potential seemed limitless.” The music was a reaction to the 70s mega-rock legacy—big names, big jam sessions, big egos. “We found it a bit impersonal,” says Andy. “We don’t think you have to be a great musician to be allowed to play and get a message out. I guess that’s what punk was all about, getting rid of the ego and getting right down to it without having to be a session guitarist. We certainly didn’t know anything about playing music when we first started. In fact, our only true musician is Alan Wilder.”

“Their music just hits kids right between the eyes,” explains KROQ DJ Richard Blade, who largely broke Depeche Mode on the west coast. “They can relate to Martin’s songs because he doesn’t write about love the way, say Richard Marx does, who comes up with ‘I love you, I lost you, I’m sad.’ Martin is about angst, about teenage love when it feels like the end of the world. You’re so self-conscious that when somebody looks at you the wrong way, it can be devastating.”

To Kelly, for instance, “Strangelove” has become almost a kind of mantra. “It talks about all the strange feelings you go through, you know? Lines like ‘Strange highs and strange lows, will you give it to me? I will take the pain.’ And their new song, ‘Clean,’ is about getting out of that pain and changing your routine. I just went through something like that with this guy. He was false to me, kind of like in ‘Policy of Truth.’”

“It’s real existential music,” says Ken Patronis, a 28-year-old fan who works as a biostatisticain at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Ken bought Speak & Spell at a time when he was also buying Bauhaus, early New Order and early Cure. But those bands have either parted ways or let him down. “I don’t really listen to the Cure anymore and New Order’s doing music for ‘America’s Most Wanted.’ That kind of says it all. But with Depeche Mode, I know that I’ll probably like whatever they put out. I guess I’m more prone to understand a song about feeling socially detached than your average Joe Blow. The band doesn’t hit you over the head with this macho stance that so many pop bands have.”

[Spin, September 28 2017, Written By Marisa Fox]

Story: Pop a La Mode

Depeche Mode may not look dangerous. They certainly don't sound dangerous. Fact is, they're not dangerous. But watch out for their fans.

The last time Depeche Mode came to the US they caused a riot. A real riot—bottles thrown, windows shaken, lots of pressing, pushing and punching. Some 20,000 fans, many of them teenaged girls, had gathered at the Warehouse in Los Angeles for an in-store appearance. Some had waited for days. Fearing for the safety of the group, security guards disbanded the affair after a scant 45 minutes.

The crowd went wild; a few had to be taken to the hospital with minor injuries. Kelly Jaffray’s mom got jabbed in the ribs, so she punched some guy in the jaw. Depeche super-fan Kelly, 15, was herself safe in the VIP section of the store. “The band all know me and they let me in without any hassles,” she boasts.

It’s true, too. In fact, when Depeche’s Andy Fletcher spotted Kelly, he gasped, “We can’t go anywhere without you.” “He was just joking,” Kelly says. “I mean they respect me because I don’t invade their space all the time. I’m not a groupie or anything. Like, I wouldn’t just sleep with them or anything. Or like, they couldn’t force me to take drugs, you know. But then, they wouldn’t. I know them and respect them and they respect me.”

In many ways, Kelly is a typical valley girl. A teenager with blue eyes and softly waved blond hair, she loves to shop on Melrose and Hollywood. She buys Quick Silver and other neon surf clothes, wears Ug boots without socks, cruises with the guys cranking KROQ on the car stereo. She says things like “Oh my gosh,” she’s getting a BMW for her Sweet Sixteen and she’d never get into a car without a box of Depeche Mode tapes.

Kelly can’t quite get through a day without listening to Depeche Mode. Her obsession has been going strong for years; it started with a single and a concert ticket. Now, 325 albums later, Kelly is one of their biggest collectors in the US, possibly the world. Her life revolves around Depeche Mode—she goes on trips to New York just to shop for Depeche paraphernalia. This year she’s hoping to go to London to get even more colored vinyl, rare remixes, posters and books. Kelly would go to any length for her fix. “If I had to I might sacrifice my life for the sake of he group,” she says, sighing.

Kelly’s mom understands. “When I was Kelly’s age I was into the Stones and drag racing. These kids aren’t as rowdy as we were, and that’s good. That’s why I encourage it. It’s a healthier habit than hanging out at the Jack in the Box and getting mixed up in a drive-by, or taking drugs and drinking.” Her mom may have bopped along to “Satisfaction,” but Kelly grooves to “Shake the Disease.” Instead of the raunchy twang of Keith Richard’s guitar, Kelly gets off on punchy rhythms programmed on synthesizers and drum machines.

Kelly was 13 when she first managed to catch a glimpse of her idols, backstage at the MTV Music Awards. “I was determined to meet them so I asked this guy who was an Aerosmith roadie to please help me. And he gave me a pass and I couldn’t believe it. There they were,” she says. “I first met their sound man, this guy named Darrel, and then I hung out with Alan Wilder. I was holding this old program from one of their shows and Martin Gore just came over and grabbed it and we started talking like we were friends.”

Kelly could go on for hours, about the time she almost had dinner with them, the time she was up at KROQ with them, about the record company bigwigs she’s met at their parties, about the 90 DM buttons she wore on her jacket for a special party, about some girl she saw leaving her hotel, all smiles and skirt half-unzipped.

“It’s strange that we appeal to so many young kids but these aren’t our only fans,” says Andy Fletcher. “We have quite a lot who are older and who have been with us since the very start, for almost 10 years.” Back in the early 80s, at the dawn of British synth-pop, Depeche Mode was more or less an underground act. As groups like Duran Duran and Human League blasted through MTV and Top 40 radio, Depeche Mode remained a faceless enigma. They were reluctant to have their picture on albums or magazines. They preferred to let their songs speak for themselves. Fronted then by Vince Clarke (who left early on to form Yaz, then Erasure), Depeche Mode were for suburban teens (Andy, Martin, Dave Gahan as lead singer and later Alan Wilder) devoted to a then-experimental instrument—the synthesizer.

“To us, it was the punk instrument,” explains the group’s songwriter Martin Gore. “It was an instant, do-it-yourself kind of tool. And because it was still new, its potential seemed limitless.” The music was a reaction to the 70s mega-rock legacy—big names, big jam sessions, big egos. “We found it a bit impersonal,” says Andy. “We don’t think you have to be a great musician to be allowed to play and get a message out. I guess that’s what punk was all about, getting rid of the ego and getting right down to it without having to be a session guitarist. We certainly didn’t know anything about playing music when we first started. In fact, our only true musician is Alan Wilder.”

“Their music just hits kids right between the eyes,” explains KROQ DJ Richard Blade, who largely broke Depeche Mode on the west coast. “They can relate to Martin’s songs because he doesn’t write about love the way, say Richard Marx does, who comes up with ‘I love you, I lost you, I’m sad.’ Martin is about angst, about teenage love when it feels like the end of the world. You’re so self-conscious that when somebody looks at you the wrong way, it can be devastating.”

To Kelly, for instance, “Strangelove” has become almost a kind of mantra. “It talks about all the strange feelings you go through, you know? Lines like ‘Strange highs and strange lows, will you give it to me? I will take the pain.’ And their new song, ‘Clean,’ is about getting out of that pain and changing your routine. I just went through something like that with this guy. He was false to me, kind of like in ‘Policy of Truth.’”

“It’s real existential music,” says Ken Patronis, a 28-year-old fan who works as a biostatisticain at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Ken bought Speak & Spell at a time when he was also buying Bauhaus, early New Order and early Cure. But those bands have either parted ways or let him down. “I don’t really listen to the Cure anymore and New Order’s doing music for ‘America’s Most Wanted.’ That kind of says it all. But with Depeche Mode, I know that I’ll probably like whatever they put out. I guess I’m more prone to understand a song about feeling socially detached than your average Joe Blow. The band doesn’t hit you over the head with this macho stance that so many pop bands have.”