- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

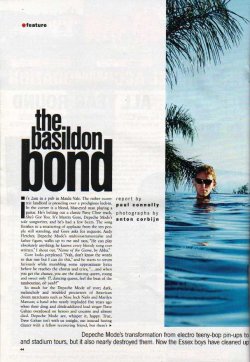

THE BASILDON BOND

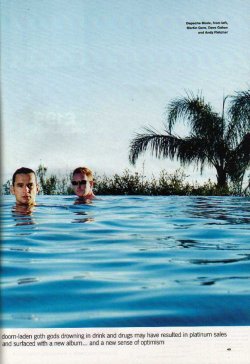

[The Times Magazine, 14th April 2001. Words: Paul Connolly. Pictures: Anton Corbijn.]

Compelling and balanced article with contributions from all band members telling the band's story and promoting Exciter. It's refreshing to see more from Martin and Andy, who bounce off each other throughout, and the article opens with a devotion-inducing vignette of Martin singing and playing under the influence in a pub.

" The relationship between Gore and Fletcher is relaxed but spiky (Fletcher hates being called The General). They're clearly very good friends, and as the evening unfolds evidently great drinking buddies, too. There's also very little rock star nonsense about them - when Fletcher's asked if he resents Gore writing all the songs he responds with: "I would be if I could write songs but I'm rubbish - I can't get beyond the first line, 'I woke up this morning'."

It's 2am in a pub in Maida Vale. The rather eccentric landlord is presiding over a prodigious lock-in. In the corner is a blond, blue-eyed man playing a guitar. He's belting out a classic Patsy Cline track, She's Got You. It's Martin Gore, Depeche Mode's sole songwriter, and he's had a few beers. The song finishes to a smattering of applause from the ten people still standing, and Gore asks for requests. Andy Fletcher, Depeche Mode's multi-instrumentalist and father figure, walks up to me and says, "He can play absolutely anything; he knows every bloody song ever written." I shout out "Name of the Game, by Abba." [1]

Gore looks perplexed. "Nah, don't know the words to that one but I can do this," and he starts to strum furiously while mumbling some approximate lyrics before he reaches the chorus and cries, "...and when you get the chance, you are the dancing queen, young and sweet only 17, dancing queen, feel the beat of the tambourine, oh yeah!"

So much for the Depeche Mode of yore; dark, melancholy and troubled precursors of American doom merchants such as Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson; a band who nearly imploded five years ago when their drug and drink-addicted lead singer Dave Gahan overdosed on heroin and cocaine and almost died. Depeche Mode are, whisper it, happy. True, Dave Gahan isn't with us tonight, out instead having dinner with a fellow recovering friend, but there's a real sense of rebirth about the Essex boys made good.

Finally, after years of trying to prove themselves to the sceptical critical establishment, they've realised that they no longer need to impress anyone. Depeche Mode, after all, are one of the most influential bands of the past 20 years, and have been prime movers in movements as diverse as techno and goth. They have nothing left to prove and with their most turbulent years behind them have produced, in their new album Exciter, a suitably relaxed, confident, positive record.

Earlier in the day, In London's Home House, before it all got a little blurred around the edges for his two colleagues, Gahan concurred. "Yeah, it is a really optimistic record. But we've all got reason to be optimistic now."

The singer, 39 next month, has recovered his saturnine pretty-boy looks. But it's been a long haul. He suffered his near fatal overdose (his heart stopped beating for two minutes) in Los Angeles on May 28, 1996. He was revived by paramedics, but was promptly arrested for possession and spent two days in prison. As soon as he was released he scored more heroin. "I didn't know how I was going to get myself out of this one, and there weren't a lot of people around me at the time who were interested in getting me out of it either. If it wasn't for our manager, Jonathan Kessler, I probably wouldn't have made it. He saw me messed up yet again and said, 'I can't deal with this any more, I can't do this, and I'm not going to watch you doing this to yourself.' And he went off in tears.

"That hit me hard. And then it was a struggle. I wanted to change, but I didn't realise how hard it was going to be." Gahan, with considerable pressure from Gore and Fletcher, booked into rehab on June 6, and after five days of seizures so bad he had to be tied down, he went clean. He's been clean ever since, but the singer has always had the seeds of self-destruction lurking beneath the surface.

Born, according to fellow Basildonian Gore, "on the wrong side of the tracks in Basildon," Gahan's father left his mother when he was a toddler. His mother married again, but Gahan's stepfather died when he was nine. Gahan smiles. "From the age of about 12 I was getting into trouble. I was a proper tearaway. I was nicking cars, joy-riding, writing graffiti. I wasn't such a bright graffiti artist either. Used my surname as my graffiti tag. There weren't too many Gahans in the whole of England never mind Basildon. I was arrested a fair few times. Not a very good villain."

But he doesn't take the easy way out when it comes to apportioning blame for his behaviour either then, or later when he developed his drug habit. "It was in my genes," he says. "I would have been the way I was whether or not my dad left when I was young. My dad died in 1990 and after that I got a bit curious about him and asked my mum about him. I think he liked a drink. She only had a couple of pictures of him, but one of them was him in a pub. I thought, 'Yeah, that's my old man all right.'"

The Depeche Mode story is an odd one. Formed in 1979, the group's early line-up featured Vince Clarke (who left to form Yazoo with Alison Moyet in 1981 after writing Depeche Mode's debut album, Speak and Spell), and their music was bright, melodious electronic pop, with singles such as Just Can't Get Enough and New Life. They enjoyed commercial success, but the critics slaughtered them for being too lightweight. When the extravagantly tonsured Gore assumed the songwriting mantle, the dynamics shifted. The songs became darker, the imagery decidedly gothic and the beats heavier. Along with New Order's bass-heavy electronica, Depeche Mode's music, heavily reliant on clattering drum machines and monumental synthscapes, was a major influence on the techno/house explosion in Detroit in the late Eighties. But still the UK wouldn't take them seriously.

In a rather garish suite in Home House, the hugely amiable but slight Martin Gore, still looking impossibly youthful, remains a little bitter about the British press. "We were hated over here in the Eighties because we were electronic pop," he says, "so we made a concerted effort to play everywhere else to prove to ourselves that we were a proper band."

It was in America that they really made their mark. After years of solid touring in the US, 1990's Violator was their breakthrough album, selling 6 million copies. They were suddenly a stadium band, and it wasn't long before the concomitant excess set in. The mammoth 1993-1994 world tour promoting Songs of Faith and Devotion, the follow-up to Violator, saw the band employing a full-time drug dealer and a full-time psychiatrist. Andy Fletcher, 39, and these days called The General by Gore because of his good-natured bossiness, allegedly suffered a nervous breakdown and left the tour early. The band were travelling in separate limos. The electro-pop moppets from Basildon who had spent much of the Eighties telling Smash Hits readers their favourite colours, were now subsumed by full-on Spinal Tap lunacy.

[The Times Magazine, 14th April 2001. Words: Paul Connolly. Pictures: Anton Corbijn.]

Compelling and balanced article with contributions from all band members telling the band's story and promoting Exciter. It's refreshing to see more from Martin and Andy, who bounce off each other throughout, and the article opens with a devotion-inducing vignette of Martin singing and playing under the influence in a pub.

" The relationship between Gore and Fletcher is relaxed but spiky (Fletcher hates being called The General). They're clearly very good friends, and as the evening unfolds evidently great drinking buddies, too. There's also very little rock star nonsense about them - when Fletcher's asked if he resents Gore writing all the songs he responds with: "I would be if I could write songs but I'm rubbish - I can't get beyond the first line, 'I woke up this morning'."

It's 2am in a pub in Maida Vale. The rather eccentric landlord is presiding over a prodigious lock-in. In the corner is a blond, blue-eyed man playing a guitar. He's belting out a classic Patsy Cline track, She's Got You. It's Martin Gore, Depeche Mode's sole songwriter, and he's had a few beers. The song finishes to a smattering of applause from the ten people still standing, and Gore asks for requests. Andy Fletcher, Depeche Mode's multi-instrumentalist and father figure, walks up to me and says, "He can play absolutely anything; he knows every bloody song ever written." I shout out "Name of the Game, by Abba." [1]

Gore looks perplexed. "Nah, don't know the words to that one but I can do this," and he starts to strum furiously while mumbling some approximate lyrics before he reaches the chorus and cries, "...and when you get the chance, you are the dancing queen, young and sweet only 17, dancing queen, feel the beat of the tambourine, oh yeah!"

So much for the Depeche Mode of yore; dark, melancholy and troubled precursors of American doom merchants such as Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson; a band who nearly imploded five years ago when their drug and drink-addicted lead singer Dave Gahan overdosed on heroin and cocaine and almost died. Depeche Mode are, whisper it, happy. True, Dave Gahan isn't with us tonight, out instead having dinner with a fellow recovering friend, but there's a real sense of rebirth about the Essex boys made good.

Finally, after years of trying to prove themselves to the sceptical critical establishment, they've realised that they no longer need to impress anyone. Depeche Mode, after all, are one of the most influential bands of the past 20 years, and have been prime movers in movements as diverse as techno and goth. They have nothing left to prove and with their most turbulent years behind them have produced, in their new album Exciter, a suitably relaxed, confident, positive record.

Earlier in the day, In London's Home House, before it all got a little blurred around the edges for his two colleagues, Gahan concurred. "Yeah, it is a really optimistic record. But we've all got reason to be optimistic now."

The singer, 39 next month, has recovered his saturnine pretty-boy looks. But it's been a long haul. He suffered his near fatal overdose (his heart stopped beating for two minutes) in Los Angeles on May 28, 1996. He was revived by paramedics, but was promptly arrested for possession and spent two days in prison. As soon as he was released he scored more heroin. "I didn't know how I was going to get myself out of this one, and there weren't a lot of people around me at the time who were interested in getting me out of it either. If it wasn't for our manager, Jonathan Kessler, I probably wouldn't have made it. He saw me messed up yet again and said, 'I can't deal with this any more, I can't do this, and I'm not going to watch you doing this to yourself.' And he went off in tears.

"That hit me hard. And then it was a struggle. I wanted to change, but I didn't realise how hard it was going to be." Gahan, with considerable pressure from Gore and Fletcher, booked into rehab on June 6, and after five days of seizures so bad he had to be tied down, he went clean. He's been clean ever since, but the singer has always had the seeds of self-destruction lurking beneath the surface.

Born, according to fellow Basildonian Gore, "on the wrong side of the tracks in Basildon," Gahan's father left his mother when he was a toddler. His mother married again, but Gahan's stepfather died when he was nine. Gahan smiles. "From the age of about 12 I was getting into trouble. I was a proper tearaway. I was nicking cars, joy-riding, writing graffiti. I wasn't such a bright graffiti artist either. Used my surname as my graffiti tag. There weren't too many Gahans in the whole of England never mind Basildon. I was arrested a fair few times. Not a very good villain."

But he doesn't take the easy way out when it comes to apportioning blame for his behaviour either then, or later when he developed his drug habit. "It was in my genes," he says. "I would have been the way I was whether or not my dad left when I was young. My dad died in 1990 and after that I got a bit curious about him and asked my mum about him. I think he liked a drink. She only had a couple of pictures of him, but one of them was him in a pub. I thought, 'Yeah, that's my old man all right.'"

The Depeche Mode story is an odd one. Formed in 1979, the group's early line-up featured Vince Clarke (who left to form Yazoo with Alison Moyet in 1981 after writing Depeche Mode's debut album, Speak and Spell), and their music was bright, melodious electronic pop, with singles such as Just Can't Get Enough and New Life. They enjoyed commercial success, but the critics slaughtered them for being too lightweight. When the extravagantly tonsured Gore assumed the songwriting mantle, the dynamics shifted. The songs became darker, the imagery decidedly gothic and the beats heavier. Along with New Order's bass-heavy electronica, Depeche Mode's music, heavily reliant on clattering drum machines and monumental synthscapes, was a major influence on the techno/house explosion in Detroit in the late Eighties. But still the UK wouldn't take them seriously.

In a rather garish suite in Home House, the hugely amiable but slight Martin Gore, still looking impossibly youthful, remains a little bitter about the British press. "We were hated over here in the Eighties because we were electronic pop," he says, "so we made a concerted effort to play everywhere else to prove to ourselves that we were a proper band."

It was in America that they really made their mark. After years of solid touring in the US, 1990's Violator was their breakthrough album, selling 6 million copies. They were suddenly a stadium band, and it wasn't long before the concomitant excess set in. The mammoth 1993-1994 world tour promoting Songs of Faith and Devotion, the follow-up to Violator, saw the band employing a full-time drug dealer and a full-time psychiatrist. Andy Fletcher, 39, and these days called The General by Gore because of his good-natured bossiness, allegedly suffered a nervous breakdown and left the tour early. The band were travelling in separate limos. The electro-pop moppets from Basildon who had spent much of the Eighties telling Smash Hits readers their favourite colours, were now subsumed by full-on Spinal Tap lunacy.

[1] Martin modestly parries Fletch's assertion in this article.

Martin Gore 60 Second Interview Martin Gore (Metro, 2003)

60 Second Interview: Martin Gore [Metro, 28th April 2003. Words: James Ellis.] A free newspaper given out on UK public transport goes into an interview with Martin armed with nothing but stereotypes: Basildon, the 1980's, skirts, doom and gloom. Martin tries gallantly to conceal his impatience...dmremix.pro