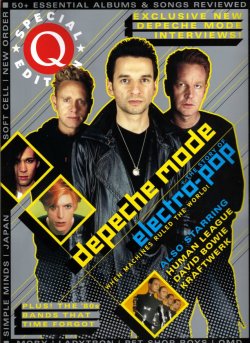

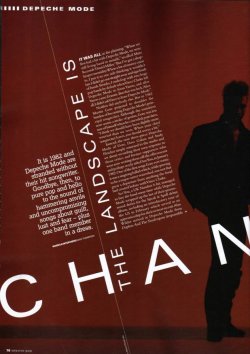

The Landscape Is Changing

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Dave Thompson. Pictures: Eric Watson / Uncredited.]

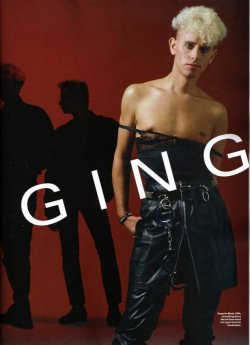

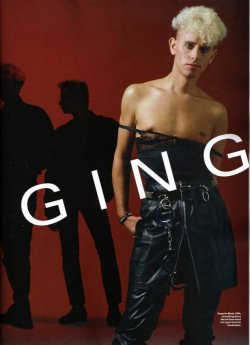

It is 1982 and Depeche Mode are stranded without their hit songwriter. Goodbye, then, to pure pop and hello to the sound of hammering anvils and uncompromising songs about guilt, lust and fear – plus one band member in a dress.

It was all in the planning. “When we first had a hit with Depeche Mode, we were still living hand to mouth,” recalled Mute Records’ Daniel Miller. “But I’ve got a shopkeeper mentality. When a lot of money came in, I put it to one side thinking it wouldn’t last. I didn’t go out straight away and sign loads of bands. Besides, I ended up with two huge pop bands by default when Vince Clarke left Depeche Mode to form Yazoo, and after Yazoo came Erasure. But that was luck. After all, I didn’t ask Vince to leave Depeche Mode.”

Neither did anybody else. But in 1982 Martin Gore prepared to shoulder the burden of becoming Depeche Mode’s principal songwriter. Although the transition now seems a stroke of genius, Gore was less sure of himself when he conceded, years later, “I think we should have been slightly more worried than we were. When your chief songwriter leaves, you should worry a bit.”

Instead, the now three-piece Depeche Mode of Gore, Dave Gahan and Andy Fletcher simply returned to the studio and set about recording their own response to those critics and former supporters who were now writing them off: the effervescent and perhaps wryly titled See You, in January 1982. One of the first songs Gore ever wrote, it was a singalong ballad which, while proving to be a major career watershed, was not that great a departure from anything the band had created before with Vince Clarke.

See You, a UK Number 6 hit, managed to buy the band some time while Depeche Mode wrapped up the last of their promotional duties for the Speak & Spell debut album, including an introductory tour of the US in February which served as an apprenticeship for their newest recruit. Alan Wilder arrived in Depeche Mode from Daphne And The Tenderspots (responsible for the Disco Hell 45) via The Hitmen. He was immediately informed that he was there simply to make up the numbers. Wilder would not be permitted to write or help arrange songs and would not even be joining the band in the studio. He was also on a six-month trial, sufficient to see the band through a season of live work, but nothing more.

It was a calculated decision. Although Wilder was an experienced musician and something of a dab hand in the recording studio, of all the challenges that faced Depeche Mode in the aftermath of Vince Clarke’s departure the need to prove that they could cut it without him was the most pressing. In their minds, this meant cutting it without anybody else at all. Only Miller and his own studio team of Eric Radcliffe and John Fryer were present as the trio set about making their second album, gathering up what Gore described as “a mishmash… of songs that were written over a very long period of time”, and which had been slowly introduced into the live set over the past six months. Perversely, its creators quickly dismissed the end result, 1982’s A Broken Frame album, as a mistake.

“People were letting us drift,” Gahan complained. “There was a lack of enthusiasm.”

In fact, A Broken Frame would help establish many of the foundations around which Depeche Mode’s next stage would develop. Initially, though, their musical aspirations seemed a little too obvious: be it the ghost of Bowie’s V2 Schneider in My Secret Garden or the album’s overall deployment of Giorgio Moroder-style sonic trickery.

Even more restrictive was the group’s awareness that only the critics would be judging them on the extent of their adventurousness. As far as their still predominantly teenage fans were concerned, all A Broken Frame needed to do was continue business as before, which it did with the simple pop of A Photograph Of You and their next single, The Meaning Of Love, complete with sickly promo video.

Even that, though, was to prove significant. Although Gahan insisted, “Martin can still write lightweight, poppy songs”, The Meaning Of Love was to be the last Depeche Mode single to mine these mawkish depths. Two hit singles sans Clarke confirmed that the band’s audience hadn’t simply drifted away. Now, Gahan continued, they wanted “to try something totally different, just to see if we can.” The group’s next single in August, Leave In Silence, was a slower, more melancholy track that eschewed the instant thrills of the group’s past hooks, and left even the singer admitting, “It wasn’t catchy. You had to hear it several times before it really began to make sense.”

Still, it reached Number 18 on the UK chart, a fair return for a song that the press had dismissed as commercial near-suicide. The band also succeeded in creating a subtle response to the many critics who’d pegged them as “banal inno-paps” (as NME’s Paul Morley dubbed them) capable only of pumping out their “bland inoffensive pop music” (poet Attila The Stockbroker) forever more. Even Paul Weller, then preparing to return with The Style Council, was moved to insist, “I’ve heard more melody coming out of an arsehole,” while the hardly heavyweight Bananarama added their voice to the chorus of disapproval by dismissing Depeche Mode as “wimps”.

The wimps remained unrepentant. Leave In Silence was not a one-off. “We want to get deeper into the album-oriented market,” Gahan said. “Bands like Echo And The Bunnymen and Simple Minds do well in both charts. We just want to produce a really fine album that will establish us as a major act.”

[Q, 14th January 2005. Words: Dave Thompson. Pictures: Eric Watson / Uncredited.]

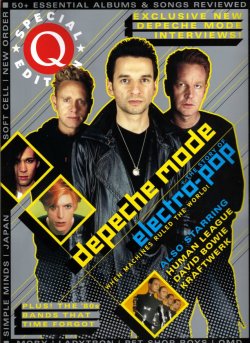

The second of a three-part marathon band history in a Q Special Edition, this section covering the band's rising years from See You to Rose Bowl. While there are some very enthusiastic and perceptive comments, the article overall is the usual chronological plod through the back catalogue. A perfectly serviceable piece, but nothing you haven't seen before.

" Black Celebration twists from poignant, yearning ballads (A Question Of Lust may be Gore’s finest hour) to relentless bitterness (Here Is The House, A Question Of Time), until its grooves are transformed into a gala of melancholy, a celebration of emotional misery and uncertainty. "

It is 1982 and Depeche Mode are stranded without their hit songwriter. Goodbye, then, to pure pop and hello to the sound of hammering anvils and uncompromising songs about guilt, lust and fear – plus one band member in a dress.

It was all in the planning. “When we first had a hit with Depeche Mode, we were still living hand to mouth,” recalled Mute Records’ Daniel Miller. “But I’ve got a shopkeeper mentality. When a lot of money came in, I put it to one side thinking it wouldn’t last. I didn’t go out straight away and sign loads of bands. Besides, I ended up with two huge pop bands by default when Vince Clarke left Depeche Mode to form Yazoo, and after Yazoo came Erasure. But that was luck. After all, I didn’t ask Vince to leave Depeche Mode.”

Neither did anybody else. But in 1982 Martin Gore prepared to shoulder the burden of becoming Depeche Mode’s principal songwriter. Although the transition now seems a stroke of genius, Gore was less sure of himself when he conceded, years later, “I think we should have been slightly more worried than we were. When your chief songwriter leaves, you should worry a bit.”

Instead, the now three-piece Depeche Mode of Gore, Dave Gahan and Andy Fletcher simply returned to the studio and set about recording their own response to those critics and former supporters who were now writing them off: the effervescent and perhaps wryly titled See You, in January 1982. One of the first songs Gore ever wrote, it was a singalong ballad which, while proving to be a major career watershed, was not that great a departure from anything the band had created before with Vince Clarke.

See You, a UK Number 6 hit, managed to buy the band some time while Depeche Mode wrapped up the last of their promotional duties for the Speak & Spell debut album, including an introductory tour of the US in February which served as an apprenticeship for their newest recruit. Alan Wilder arrived in Depeche Mode from Daphne And The Tenderspots (responsible for the Disco Hell 45) via The Hitmen. He was immediately informed that he was there simply to make up the numbers. Wilder would not be permitted to write or help arrange songs and would not even be joining the band in the studio. He was also on a six-month trial, sufficient to see the band through a season of live work, but nothing more.

It was a calculated decision. Although Wilder was an experienced musician and something of a dab hand in the recording studio, of all the challenges that faced Depeche Mode in the aftermath of Vince Clarke’s departure the need to prove that they could cut it without him was the most pressing. In their minds, this meant cutting it without anybody else at all. Only Miller and his own studio team of Eric Radcliffe and John Fryer were present as the trio set about making their second album, gathering up what Gore described as “a mishmash… of songs that were written over a very long period of time”, and which had been slowly introduced into the live set over the past six months. Perversely, its creators quickly dismissed the end result, 1982’s A Broken Frame album, as a mistake.

“People were letting us drift,” Gahan complained. “There was a lack of enthusiasm.”

In fact, A Broken Frame would help establish many of the foundations around which Depeche Mode’s next stage would develop. Initially, though, their musical aspirations seemed a little too obvious: be it the ghost of Bowie’s V2 Schneider in My Secret Garden or the album’s overall deployment of Giorgio Moroder-style sonic trickery.

Even more restrictive was the group’s awareness that only the critics would be judging them on the extent of their adventurousness. As far as their still predominantly teenage fans were concerned, all A Broken Frame needed to do was continue business as before, which it did with the simple pop of A Photograph Of You and their next single, The Meaning Of Love, complete with sickly promo video.

Even that, though, was to prove significant. Although Gahan insisted, “Martin can still write lightweight, poppy songs”, The Meaning Of Love was to be the last Depeche Mode single to mine these mawkish depths. Two hit singles sans Clarke confirmed that the band’s audience hadn’t simply drifted away. Now, Gahan continued, they wanted “to try something totally different, just to see if we can.” The group’s next single in August, Leave In Silence, was a slower, more melancholy track that eschewed the instant thrills of the group’s past hooks, and left even the singer admitting, “It wasn’t catchy. You had to hear it several times before it really began to make sense.”

Still, it reached Number 18 on the UK chart, a fair return for a song that the press had dismissed as commercial near-suicide. The band also succeeded in creating a subtle response to the many critics who’d pegged them as “banal inno-paps” (as NME’s Paul Morley dubbed them) capable only of pumping out their “bland inoffensive pop music” (poet Attila The Stockbroker) forever more. Even Paul Weller, then preparing to return with The Style Council, was moved to insist, “I’ve heard more melody coming out of an arsehole,” while the hardly heavyweight Bananarama added their voice to the chorus of disapproval by dismissing Depeche Mode as “wimps”.

The wimps remained unrepentant. Leave In Silence was not a one-off. “We want to get deeper into the album-oriented market,” Gahan said. “Bands like Echo And The Bunnymen and Simple Minds do well in both charts. We just want to produce a really fine album that will establish us as a major act.”