- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

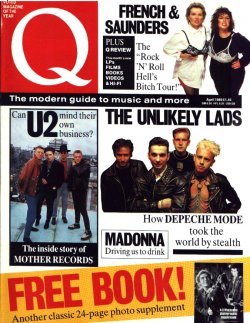

The Unlikely Lads

[Q, April 1989. Words: Mat Snow. Pictures: Various.]

It is a balmy June evening in the well-heeled Los Angeles neighbourhood of Pasadena, and 72,000 fans congregated in the Rose Bowl are baying for a group who have been so long part of pop’s furniture in their native UK that such adulation is hard to credit. But there it is – Depeche Mode are massive in the state of California, which, if it had sovereign status, would rank as the ninth richest country in the world. And this, the 101st concert in Depeche Mode’s 1988 world tour, capstones their global growth over the last seven years. This crowning achievement, moreover, is to be filmed by none other than D. A. Pennebaker, whose mid-’60s ‘rockumentaries’ Don’t Look Back (with Bob Dylan) and Monterey Pop remain masterpieces of fly-on-the-wall and in-concert footage.

Small wonder then that singer Dave Gahan, normally an unruffled pro before a gig, has never been so nervous in his life. What do you say to 72,000 fans? Backstage, members of the Mode entourage are batting a few ideas back and forth, looking for something to reflect the significance of the event about to take place. Someone comes up with a suggestion, and as greetings go it hardly rivals the welcoming address at a village fete, but it lacks the pithiness Dave is after. “What do you think I am?” he demands, cheeky bravado ill-concealing his apprehension. “Fucking Wordsworth?”

In the end he settles for the succinct “Good evening Pasadena…”

Nine months after that climactic show, Depeche Mode are about to give birth to those by now familiar rock industry twins, the live double album and the movie, both titled 101. A concert version of their 1983 hit single Everything Counts blazes a trail for both projects and neatly encapsulates a theme they have in common, one that seldom is publicly aired by pop groups – the fact that they have made “tons of money”, in the gleeful words of their merchandising man at the Rose Bowl as he counts wads and wads of the stuff taken by the T-shirt stalls. A ballpark figure? One million dollars minimum in T-shirt sales alone from just that single show.

“It was a dig at America, the way money corrupts,” is Dave Gahan’s analysis today. It’s an argument perhaps polished to a high gleam over the last three days. For Depeche Mode have been flying in, and entertaining at their own considerable expense, pop journalists from all over the world for some marathon PR to launch 101 in all its manifestations. I’m the token representative of the UK, a country of greater sentimental than commercial value to the Depeche Mode of 1989.

“When you tour America, suddenly things like merchandising are far more important than ticket sales,” Dave continues, hoarse from the interview rounds. “Merchandise finances tours. People talk about million dollar deals with merchandisers. Before you know it, you may as well be running a chain of T-shirt shops. To tour in America you need to sell T-shirts.

“We like the idea of being quite open about these things, and we hope that people take it the right way. It’s something that’s always taboo with bands, though everybody knows that bands make lots of money, sometimes far too much for what they do. But you must never talk about that because it detaches you from your audience who are supposed to be on the same level as you.”

This won’t be the first time Depeche Mode have played fast and loose with their audience, though perversity for its own sake has never been part of the gameplan. We first met them back in 1981, four lads from Basildon, Essex, who sang catchy, danceable ditties which made use of the newly affordable and accessible synthesizer technology that had been pioneered in the charts the previous year by Soft Cell and Human League. Depeche Mode had scored by joining forces with another innovator of what became excruciatingly termed “synthi-pop” – Daniel Miller, a behind-the-scenes boffin who made cult hit records in the guise of The Silicon Teens and The Normal (whose Warm Leatherette was successfully covered by Grace Jones). Daniel Miller’s Mute Records was founded with the purpose of providing a like-minded record company for enthusiasts of the new technology, and his offer to the budding Mode to put out one single, with the possibility of more if it went well, prevailed over the lucrative bids waved in their faces by the majors. Back then Depeche Mode felt they were too young to make a three-album commitment; besides, only Daniel struck the band as entirely honest.

In 1981-2 Depeche Mode could align themselves with Beckenham’s Haircut 100: wholesome, user-friendly boys-next-door, chirpy rather than handsome, guaranteed free of rock posturing and student mystique. The vanguard, in short, of pop’s New Era. It didn’t last. Haircut 100 split and the individuals couldn’t maintain their impetus. By contrast, when principal composer Vince Clarke quit Depeche to form Yazoo with Alison Moyet, Martin Gore stepped into the songwriting gap and immediately took the band into a stranger, more unsettling direction – eastwards, to Europe.

Not only had Dusseldorf’s Kraftwerk long influenced the band, but a new generation of ‘industrial’ groups was coming to the fore, headed by West Berlin’s Einsturzende Neubaten, whose calculated musical dissonance and fetishist image fired Martin Gore’s imagination. The Basildon boys grinning on Saturday Superstore began putting out records called things like Shake The Disease, Master And Servant, Strangelove, Blasphemous Rumours, Stripped and Black Celebration. The world, starting with West Germany, pricked up its ears.

Britain, on the other hand, couldn’t quite handle the transformation. Whereas New Order, operating in similar territory, are treated with awed fascination, Depeche Mode are regarded as something of a joke – a reflection, perhaps, of the fact that New Order’s image has been shaped by the serious rock music press while Mode first beamed forth from the cover of Smash Hits.

“The problem with this country is that we’ve always been underrated artistically,” Dave moans. “Earlier on in our career we felt we had to be in everything, the more the better. We were very naïve and because of that we were taken totally the wrong way. We’ve always been very honest. The British press have found it hard to understand Depeche Mode, though I don’t think we’re hard to understand at all. We’ve always had to justify ourselves to the press in Britain and that really offends us; that’s why we’ve avoided talking to them in the last few years. We don’t feel we really have anything to say when the line of questioning is, Why do you exist? That’s another reason to make this film; we wanted to be portrayed as we really were, and if we’re still considered dickheads, then fair enough.”

[Q, April 1989. Words: Mat Snow. Pictures: Various.]

" This is Depeche Mode’s American constituency; the largely urban rock fans who do not buy into the unmistakably American roots sound typified by Bruce Springsteen. To these Americans, Basildon and Berlin are as fascinatingly exotic as New Jersey and Cleveland are to generations of European rock fans. "

In-depth, almost academic article on how Depeche Mode conquered America, both as a band and as a business. The author is heavy on the sociology and interviews a wide range of sources, while Andy and Dave talk in detail about how they have had to present themselves to an American market. Although a casual reader will do well to get to the end, this article is a goldmine for a media student or someone with a serious interest in the music business.

It is a balmy June evening in the well-heeled Los Angeles neighbourhood of Pasadena, and 72,000 fans congregated in the Rose Bowl are baying for a group who have been so long part of pop’s furniture in their native UK that such adulation is hard to credit. But there it is – Depeche Mode are massive in the state of California, which, if it had sovereign status, would rank as the ninth richest country in the world. And this, the 101st concert in Depeche Mode’s 1988 world tour, capstones their global growth over the last seven years. This crowning achievement, moreover, is to be filmed by none other than D. A. Pennebaker, whose mid-’60s ‘rockumentaries’ Don’t Look Back (with Bob Dylan) and Monterey Pop remain masterpieces of fly-on-the-wall and in-concert footage.

Small wonder then that singer Dave Gahan, normally an unruffled pro before a gig, has never been so nervous in his life. What do you say to 72,000 fans? Backstage, members of the Mode entourage are batting a few ideas back and forth, looking for something to reflect the significance of the event about to take place. Someone comes up with a suggestion, and as greetings go it hardly rivals the welcoming address at a village fete, but it lacks the pithiness Dave is after. “What do you think I am?” he demands, cheeky bravado ill-concealing his apprehension. “Fucking Wordsworth?”

In the end he settles for the succinct “Good evening Pasadena…”

Nine months after that climactic show, Depeche Mode are about to give birth to those by now familiar rock industry twins, the live double album and the movie, both titled 101. A concert version of their 1983 hit single Everything Counts blazes a trail for both projects and neatly encapsulates a theme they have in common, one that seldom is publicly aired by pop groups – the fact that they have made “tons of money”, in the gleeful words of their merchandising man at the Rose Bowl as he counts wads and wads of the stuff taken by the T-shirt stalls. A ballpark figure? One million dollars minimum in T-shirt sales alone from just that single show.

“It was a dig at America, the way money corrupts,” is Dave Gahan’s analysis today. It’s an argument perhaps polished to a high gleam over the last three days. For Depeche Mode have been flying in, and entertaining at their own considerable expense, pop journalists from all over the world for some marathon PR to launch 101 in all its manifestations. I’m the token representative of the UK, a country of greater sentimental than commercial value to the Depeche Mode of 1989.

“When you tour America, suddenly things like merchandising are far more important than ticket sales,” Dave continues, hoarse from the interview rounds. “Merchandise finances tours. People talk about million dollar deals with merchandisers. Before you know it, you may as well be running a chain of T-shirt shops. To tour in America you need to sell T-shirts.

“We like the idea of being quite open about these things, and we hope that people take it the right way. It’s something that’s always taboo with bands, though everybody knows that bands make lots of money, sometimes far too much for what they do. But you must never talk about that because it detaches you from your audience who are supposed to be on the same level as you.”

This won’t be the first time Depeche Mode have played fast and loose with their audience, though perversity for its own sake has never been part of the gameplan. We first met them back in 1981, four lads from Basildon, Essex, who sang catchy, danceable ditties which made use of the newly affordable and accessible synthesizer technology that had been pioneered in the charts the previous year by Soft Cell and Human League. Depeche Mode had scored by joining forces with another innovator of what became excruciatingly termed “synthi-pop” – Daniel Miller, a behind-the-scenes boffin who made cult hit records in the guise of The Silicon Teens and The Normal (whose Warm Leatherette was successfully covered by Grace Jones). Daniel Miller’s Mute Records was founded with the purpose of providing a like-minded record company for enthusiasts of the new technology, and his offer to the budding Mode to put out one single, with the possibility of more if it went well, prevailed over the lucrative bids waved in their faces by the majors. Back then Depeche Mode felt they were too young to make a three-album commitment; besides, only Daniel struck the band as entirely honest.

In 1981-2 Depeche Mode could align themselves with Beckenham’s Haircut 100: wholesome, user-friendly boys-next-door, chirpy rather than handsome, guaranteed free of rock posturing and student mystique. The vanguard, in short, of pop’s New Era. It didn’t last. Haircut 100 split and the individuals couldn’t maintain their impetus. By contrast, when principal composer Vince Clarke quit Depeche to form Yazoo with Alison Moyet, Martin Gore stepped into the songwriting gap and immediately took the band into a stranger, more unsettling direction – eastwards, to Europe.

Not only had Dusseldorf’s Kraftwerk long influenced the band, but a new generation of ‘industrial’ groups was coming to the fore, headed by West Berlin’s Einsturzende Neubaten, whose calculated musical dissonance and fetishist image fired Martin Gore’s imagination. The Basildon boys grinning on Saturday Superstore began putting out records called things like Shake The Disease, Master And Servant, Strangelove, Blasphemous Rumours, Stripped and Black Celebration. The world, starting with West Germany, pricked up its ears.

Britain, on the other hand, couldn’t quite handle the transformation. Whereas New Order, operating in similar territory, are treated with awed fascination, Depeche Mode are regarded as something of a joke – a reflection, perhaps, of the fact that New Order’s image has been shaped by the serious rock music press while Mode first beamed forth from the cover of Smash Hits.

“The problem with this country is that we’ve always been underrated artistically,” Dave moans. “Earlier on in our career we felt we had to be in everything, the more the better. We were very naïve and because of that we were taken totally the wrong way. We’ve always been very honest. The British press have found it hard to understand Depeche Mode, though I don’t think we’re hard to understand at all. We’ve always had to justify ourselves to the press in Britain and that really offends us; that’s why we’ve avoided talking to them in the last few years. We don’t feel we really have anything to say when the line of questioning is, Why do you exist? That’s another reason to make this film; we wanted to be portrayed as we really were, and if we’re still considered dickheads, then fair enough.”