You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

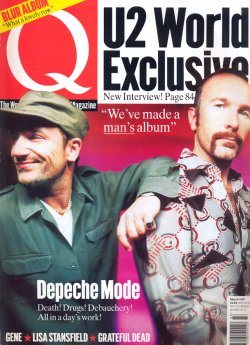

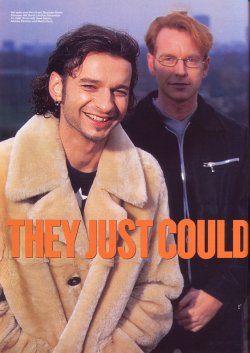

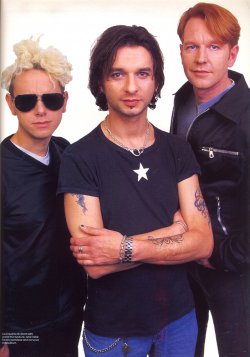

Depeche Mode They Just Couldn't Get Enough (Q, 1997)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

Detailed all-purpose article on the band's history with especial focus on their problems in the mid-nineties. The article stays at a sensible enough length not to get too heavy and is often humourous in discussing the insanities of the Devotional Tour. This article is the first section of three in a large feature; the other parts are a grilling of Dave and an album discography.

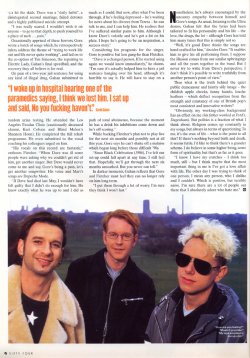

Dave Gahan - Tears Of My Tracks (Q, 1997)

Tears Of My Tracks [Q, March 1997. Words: Phil Sutcliffe. Pictures: Andy Earl.] Mercilessly-detailed in-depth conversation with Dave on all things related to his drug troubles. A lot of the narrative in this piece was used almost unchanged by Steve Malins for his biography and is a harrowing...dmremix.pro

" Gahan wangled a support spot for his presumed narcotic soulmates, Primal Scream. But, insiders allege, the Scream were so shaken by Depeche Mode's level of excess that, thenceforth, they fervently forswore sin, and the next Primal Scream album was recorded with zero input of powder, pill or spliff. Behold, then, Depeche Mode: the band who frightened Primal Scream into temperance."Depeche Mode - Personal? Jesus! (Q, 1997)

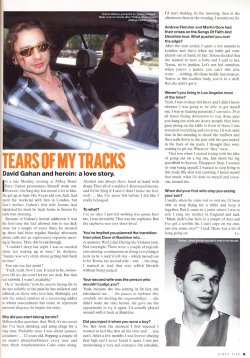

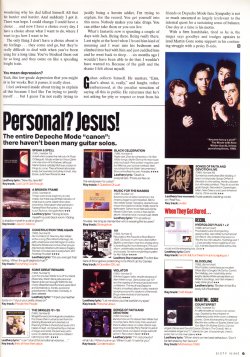

Personal? Jesus! [Q, March 1997. Words: Phil Sutcliffe.] Potted discography of Depeche Mode albums, with sleeve shots and reviews. Somewhat satirical, and look out for the sympathetic Alan Wilder references. "There haven't been many guitar solos." SPEAK & SPELL (1981, Number 10) A start...dmremix.pro

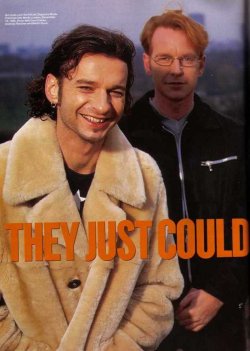

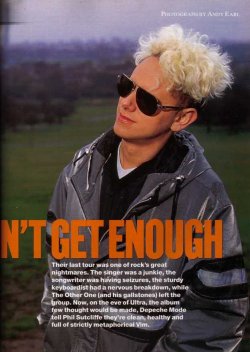

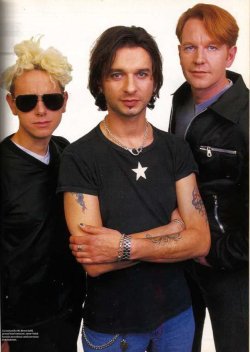

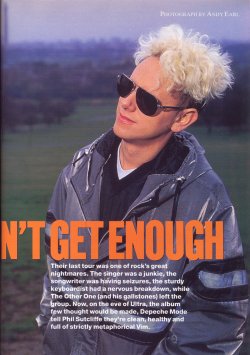

Their last tour was one of rock's great nightmares. The singer was a junkie, the songwriter was having seizures, the sturdy keyboardist had a nervous breakdown, while The Other One (and his gallstones) left the group. Now, on the eve of Ultra, the album few thought would be made, Depeche Mode tell Phil Sutcliffe they're clean, healthy and full of strictly metaphorical Vim.

"I heard it on the radio. Dave had overdosed, nearly died, then been arrested for drugs offences. That's when I thought Depeche Mode were over," reflects songwriter Martin Gore. "We'd given him so many chances..." Recollected frustration and anger glint through the rather remote tones of his oddly Mr Bean-ish speaking voice.

Gahan's latest chance - six years into a heroin addiction which had defied two stints in rehabilitation clinics, overdoses and a suicide attempt - began last spring when he joined Depeche Mode at Electric Lady, New York, to record the vocals for Ultra, their ninth studio album. Gore had written the songs and sketched in backing tracks with producer Tim Simenon. All Gahan had to do was turn up and supply the vocals.

"But he was hiding his habit from us again - lying to us" sighs Gore, with a creak of black leather trouser on black leather sofa. "Saying things like, 'Alice In Chains are in town next week, but they won't want to hang around with me any more, now I'm clean.' We got one usable vocal out of him in four weeks and we told him, 'Go home to L.A. and sort yourself out. We'll record you later in the year.' Dave seemed quite happy to go along with it."

Gore and Andrew "Fletch" Fletcher, the band's keyboard-prodding business head and strategist, flew back to London. But, not long after, came the dread newsflash.

"Of course, I felt sympathy," Gore allows. "But I also thought, How seriously is he taking this? We're slogging away and he's so (pulls back from something harsh)...ill that he's never going to be fit to carry on."

Quite a relief, then, that just along the sofa at Abbey Road, where Ultra is reaching a civilised conclusion, sits David Gahan, sound in wind and limb. Clean - and, like every recovered addict, bare-armed to prove it - he's a proper friend once more. He listens attentively to Gore and Fletcher's criticisms and shows due concern when they describe their own crises of recent years: the cerebral seizures, the nervous breakdowns and, inevitably, gallstones, which finally prompted the collective realisation that life in Depeche Mode was killing them.

"For nearly 10 years we never put a foot wrong, we made practically perfect progress," opines Fletcher, now 36. Starting in 1980, the minute they traded guitars for dinky synthesizers, they commenced a brisk development. Where once they'd covered Lieutenant Pigeon's Mouldy Old Dough, they were alchemising the inspiration of Can, David Bowie and Einsturzende Neubaten into an airy, clever, semi-industrial bip-pop. They charted as relentlessly as Sir Cliff.

The potentially terminal departure of debut album songwriter Vince Clarke (to Yazoo, and later Erasure, replaced long-term by the musicianly and studio-wise Alan Wilder) only gave Gore the cue to whip out his songbook of ambivalent ruminations on relationships, religion and politics, illuminated by distinctive S&M domination and enslavement imagery (he claims to have used the word 'knees' more often than any other lyricist). [1]

Ever whistlesome, yet dark as death at times, they made the cover of Smash Hits repeatedly while their adventures with found-sound industrial beats would influence house and techno playmakers like Todd Terry in New York and Derrick May in Detroit.

Then, in 1990, they released Violator, a career-best Number 2 in the UK and 7 in America. Worldwide sales of six million trebled those of the foregoing Music For The Masses.

"We'd been ticking along nicely, never an unbearable level of attention paid to us," Gore, 36, reminisces. "Then Violator took off and it went over the edge."

[1] - If there was a Martin Gore Dictionary, the entry for 'knees' would be quite hefty, especially with the sub-heading 'down on my ~':

"You treat me like a dog / Get me down on my knees" (Master And Servant, 1984)

"She goes down on her knees and prays" (Blasphemous Rumours, 1984)

"I'm not going down on my knees / Begging you to adore me" (Shake The Disease, 1985)

"And I will go down on my knees / When I see beauty" (Sacred, 1987)

"I feel diseased / I'm down on my knees" (To Have And To Hold, 1987)

"Well I'm down on my knees again" (One Caress, 1993)

"...the sickliest sweet-smelling sheets / That cling to the backs of my knees and my feet" (Home, 1997)

"You'll be down on your knees / You'll be begging us please" (The Dead Of Night, 2001)

...and probably more if you can find them. It's really quite a timewaster...

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

So did Dave Gahan ("Ger-haan", though he's given up trying to standardise the Irish pronunciation) [2]. Conscious that he was nearing 30, always a recreational drug user and drinker, on the World Violation tour he deliberately set about transforming himself into the rock god-cum-monster of his more garish fantasies. Introduced to Jane's Addiction circles by Teresa Conway, previously the publicist on Depeche Mode's 1988 American tour, Gahan lost touch with the shiny-faced boy of old. He acquired long hair, a goatee and loads of tattoos; ten hours of pain went into the showpiece pair of wings that illustrate his shoulder blades.

To complete the picture, he took up heroin and left his wife, childhood sweetheart Joanne, and 5-year-old son Jack. Achingly aware that he emulated his own father's desertion when he too was 5, Gahan, now 34, contrives no excuses.

"My vision got cloudier and cloudier because of what I was putting into my body."

Feeling the pressure themselves, after the tour Gore and Fletcher went home to restore their resources with 'sane domestic life'. Their first children were born. Gore withdrew to the Hertfordshire countryside with his Texan-born wife, Suzanne, and, in due course, wrote Songs Of Faith And Devotion. With his wife, Grainne, the entrepreneurial Fletch opened a restaurant, Gascoigne's, in St John's Wood.

Gahan moved to Los Angeles and married Teresa Conway in a ceremony at the Graceland Chapel, Las Vegas, serenaded by the resident fake Elvis. Smitten with grunge, enraptured by Rage Against The Machine's metal/hip hop fusion, he thought about leaving Depeche Mode. Then Gore sent him a tape of the new songs. He loved them.

So he flew to Madrid to start recording. But when he met the band for the first time in several months, they just and stared at him. He remembers the moment.

"I'd changed, but I didn't really understand it until I came face to face with Al and Mart and Fletch. The looks on their faces battered me."

Deeply disorientated by Gahan's deliberate metamorphosis, for the very first time the four found that they couldn't work together. They took a break, then reconvened at the Chateau Du Pape, a residential studio in Hamburg. The shock that greeted the new Gahan had worn off. They adjusted and progressed.

"Dave would come forward on a real burst of energy, do a vocal, then disappear to his room for a couple of days. It was a bit odd," Fletcher notes with phlegmatic understatement.

Gahan thinks it was Wilder who eventually confronted him. "He used to do quite a bit of snooping around and he found some works in my room."

"Then we had our first ultimatum-meeting with Dave," continues Gore. "We said to him, You've got to sort yourself out. You're putting yourself in danger."

"They were genuinely concerned about my health," acknowledges Gahan. "Of course, I couldn't see that. I said to Mart, Fuck off! You drink fifteen pints of beer a night and take your clothes off and cause a scene. How can you be so fucking hypocritical?"

He stormed off to immerse himself in the pleasures of his addiction's honeymoon period.

But it was Fletcher, the commonsensical 'backbone' of the band, who came apart first. He had a nervous breakdown. Hospitalised for running repairs, he discharged himself too soon. The Songs Of Faith And Devotion tour, one of rock's great nightmares, was about to begin.

They took a therapist on the road with them. It didn't really work because, although Fletch saw him occasionally, the rest of us never did," chortles Gore. "After six weeks, we knocked it on the head." [3]

Songs Of Faith And Devotion was an instant Number 1 in the United Kingdom and America. Consequently, the tour grew and grew.

"For us, more workload means more partyload," Fletcher attests. "I know it's a cliche, but wherever you go, everyone wants to scream at you, photograph you, take you out. For the night, you're the kings of the city."

"When you finish a concert and every door is open to you, it's very hard to say, Actually, I'm off to bed," argues Gore. "I went to bed early once in fourteen months on that tour - at Park West, outside Salt Lake City."

He lets rip a rare unbridled guffaw at the thought that he can remember such a thing amid the mayhem.

Their personal dislocation worsened. They took to separate limousines as well as separate dressing-rooms - Gahan's was a fetid black-candlelit lair, whence, after the show, minions would cart his smack-blasted body back to the required hotel.

To complete the picture, he took up heroin and left his wife, childhood sweetheart Joanne, and 5-year-old son Jack. Achingly aware that he emulated his own father's desertion when he too was 5, Gahan, now 34, contrives no excuses.

"My vision got cloudier and cloudier because of what I was putting into my body."

Feeling the pressure themselves, after the tour Gore and Fletcher went home to restore their resources with 'sane domestic life'. Their first children were born. Gore withdrew to the Hertfordshire countryside with his Texan-born wife, Suzanne, and, in due course, wrote Songs Of Faith And Devotion. With his wife, Grainne, the entrepreneurial Fletch opened a restaurant, Gascoigne's, in St John's Wood.

Gahan moved to Los Angeles and married Teresa Conway in a ceremony at the Graceland Chapel, Las Vegas, serenaded by the resident fake Elvis. Smitten with grunge, enraptured by Rage Against The Machine's metal/hip hop fusion, he thought about leaving Depeche Mode. Then Gore sent him a tape of the new songs. He loved them.

So he flew to Madrid to start recording. But when he met the band for the first time in several months, they just and stared at him. He remembers the moment.

"I'd changed, but I didn't really understand it until I came face to face with Al and Mart and Fletch. The looks on their faces battered me."

Deeply disorientated by Gahan's deliberate metamorphosis, for the very first time the four found that they couldn't work together. They took a break, then reconvened at the Chateau Du Pape, a residential studio in Hamburg. The shock that greeted the new Gahan had worn off. They adjusted and progressed.

"Dave would come forward on a real burst of energy, do a vocal, then disappear to his room for a couple of days. It was a bit odd," Fletcher notes with phlegmatic understatement.

Gahan thinks it was Wilder who eventually confronted him. "He used to do quite a bit of snooping around and he found some works in my room."

"Then we had our first ultimatum-meeting with Dave," continues Gore. "We said to him, You've got to sort yourself out. You're putting yourself in danger."

"They were genuinely concerned about my health," acknowledges Gahan. "Of course, I couldn't see that. I said to Mart, Fuck off! You drink fifteen pints of beer a night and take your clothes off and cause a scene. How can you be so fucking hypocritical?"

He stormed off to immerse himself in the pleasures of his addiction's honeymoon period.

But it was Fletcher, the commonsensical 'backbone' of the band, who came apart first. He had a nervous breakdown. Hospitalised for running repairs, he discharged himself too soon. The Songs Of Faith And Devotion tour, one of rock's great nightmares, was about to begin.

They took a therapist on the road with them. It didn't really work because, although Fletch saw him occasionally, the rest of us never did," chortles Gore. "After six weeks, we knocked it on the head." [3]

Songs Of Faith And Devotion was an instant Number 1 in the United Kingdom and America. Consequently, the tour grew and grew.

"For us, more workload means more partyload," Fletcher attests. "I know it's a cliche, but wherever you go, everyone wants to scream at you, photograph you, take you out. For the night, you're the kings of the city."

"When you finish a concert and every door is open to you, it's very hard to say, Actually, I'm off to bed," argues Gore. "I went to bed early once in fourteen months on that tour - at Park West, outside Salt Lake City."

He lets rip a rare unbridled guffaw at the thought that he can remember such a thing amid the mayhem.

Their personal dislocation worsened. They took to separate limousines as well as separate dressing-rooms - Gahan's was a fetid black-candlelit lair, whence, after the show, minions would cart his smack-blasted body back to the required hotel.

[2] - Aaargh! No! It's pronounced "Gaan". This is a common mistake in the press and one of Dave's pet hates (see here).

[3] - A psychiatrist and a drug dealer were part of the Devotional Tour entourage. One was used by Dave a lot, the other was intended for use by Dave. With hindsight, they perhaps knocked the wrong one on the head.Dave Gahan - Dave Gahan (Cash For Questions) (Q, 2003)

Dave Gahan: Cash For Questions [Q, June 2003. Words: Paul Stokes. James Burns.] Dave faces a round of questions from readers on all kinds of subjects and all aspects of his life and career. Plenty of unexpected comments and tidbits, and Dave's much loved cheeky swagger comes out to play. This...dmremix.pro

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

"Remember New Orleans?" enquires Gahan, with the ambivalent merriment of a man reviewing his past as a pillock. "At the end of the gig I couldn't go back for the encore, Mart had to do a song solo while all the paramedics rushed me off to hospital. I'd overdosed, I'd had a heart attack. Next day, we didn't think any more about it.

"Then there was Mart having a full grand mal seizure in the middle of a business meeting at the Sunset Marquis hotel in Los Angeles. He keeled over, banging his head on the floor, making these weird noises." [1]

"I really thought the whole tour was over," Fletcher recalls.

"That was the first thing that went through your mind, was it?" rails Gore, ever amused by Fletcher's pragmatic ways.

The songwriter regained consciousness within the hour to face severe finger-wagging from the hospital doctor. He'd had a fit brought on by stress, alcohol and the rest. Then, Gore realised that it had happened once before, when he was alone in a hotel room. He had also suffered panic attacks when his heart raced and he thought he was "going to die at any moment". Sensibly afraid, he took several steps back from the precipice.

Functional, if tawdry, order was briefly restored, with only Wilder's grumbling gallstones to fret about.

However, when, with four months left to go, the tour deplaned in Hawaii, Fletcher's fast-evolving depression reached such a bleak pitch that Gahan and Wilder approached Gore to demand his early departure.

"It was very difficult," muses Gore, unhappily. "Andy's been my closest friend since we were twelve. But, for the others, he'd become unbearable. I justified it by thinking that it would be better for him if he went home and got professional advice."

Fletcher, who was replaced by the band's PA Daryl Bamonte, brother of the Cure's Perry, saw his substitution as blessed relief. His misery had taken a peculiar turn.

"With the targets, the deadlines, the partying, the excess, I just lost it. I had an obsessive-compulsive disorder which made me displace this stress into worries about bodily symptoms. This sounds terrible, but I thought I had a brain tumour. I couldn't sleep. I couldn't think, this headache wouldn't go away. I had tests. It wasn't a brain tumour, it was a breakdown.

"Back home, I went into hospital for four weeks. I've recovered since. I took up yoga, relaxation. I think I'm a much stronger person now. Hopefully, there won't be a repeat."

The tour stumbled to its conclusion in July, 1994. For the final US leg, Gahan wangled a support spot for his presumed narcotic soulmates, Primal Scream. But, insiders allege, the Scream were so shaken by Depeche Mode's level of excess that, thenceforth, they fervently forswore sin, and the next Primal Scream album was recorded with zero input of powder, pill or spliff. Behold, then, Depeche Mode: the band who frightened Primal Scream into temperance.

Having digested the tour experience, Wilder resigned, formally stating a perhaps not unreasonable "dissatisfaction with the internal relations and working practices of the group". The others credit him with painstaking studio work, but complain that he became obsessive to the irksome point where he felt simultaneously indispensable and undervalued. Beyond even-handed analysis, they sometimes shout "Wanker!" in his general direction. (Depeche Mode did not want Q to talk to him because they felt he might be "bitter": Q tried anyway, but Wilder, who is still signed to the band's label and publisher, Mute, said he "wasn't talking to anyone yet.") If that was a difficulty resolved, off-tour Gahan hit the skids. There was a "daily habit", a disintegrated second marriage, failed detoxes and a highly publicised suicide attempt.

"I was really scared. I wouldn't wish it on anyone - to go to that depth, to push yourself to a place of such...pain."

Occasionally apprised of these horrors, Gore wrote a batch of songs which, he retrospectively infers, address the theme of "trying to work life out and life never quite working", and led on to the co-option of Tim Simenon, the repairing to Electric Lady, Gahan's final speedball, and the recovery they all believe is for real.

"Then there was Mart having a full grand mal seizure in the middle of a business meeting at the Sunset Marquis hotel in Los Angeles. He keeled over, banging his head on the floor, making these weird noises." [1]

"I really thought the whole tour was over," Fletcher recalls.

"That was the first thing that went through your mind, was it?" rails Gore, ever amused by Fletcher's pragmatic ways.

The songwriter regained consciousness within the hour to face severe finger-wagging from the hospital doctor. He'd had a fit brought on by stress, alcohol and the rest. Then, Gore realised that it had happened once before, when he was alone in a hotel room. He had also suffered panic attacks when his heart raced and he thought he was "going to die at any moment". Sensibly afraid, he took several steps back from the precipice.

Functional, if tawdry, order was briefly restored, with only Wilder's grumbling gallstones to fret about.

However, when, with four months left to go, the tour deplaned in Hawaii, Fletcher's fast-evolving depression reached such a bleak pitch that Gahan and Wilder approached Gore to demand his early departure.

"It was very difficult," muses Gore, unhappily. "Andy's been my closest friend since we were twelve. But, for the others, he'd become unbearable. I justified it by thinking that it would be better for him if he went home and got professional advice."

Fletcher, who was replaced by the band's PA Daryl Bamonte, brother of the Cure's Perry, saw his substitution as blessed relief. His misery had taken a peculiar turn.

"With the targets, the deadlines, the partying, the excess, I just lost it. I had an obsessive-compulsive disorder which made me displace this stress into worries about bodily symptoms. This sounds terrible, but I thought I had a brain tumour. I couldn't sleep. I couldn't think, this headache wouldn't go away. I had tests. It wasn't a brain tumour, it was a breakdown.

"Back home, I went into hospital for four weeks. I've recovered since. I took up yoga, relaxation. I think I'm a much stronger person now. Hopefully, there won't be a repeat."

The tour stumbled to its conclusion in July, 1994. For the final US leg, Gahan wangled a support spot for his presumed narcotic soulmates, Primal Scream. But, insiders allege, the Scream were so shaken by Depeche Mode's level of excess that, thenceforth, they fervently forswore sin, and the next Primal Scream album was recorded with zero input of powder, pill or spliff. Behold, then, Depeche Mode: the band who frightened Primal Scream into temperance.

Having digested the tour experience, Wilder resigned, formally stating a perhaps not unreasonable "dissatisfaction with the internal relations and working practices of the group". The others credit him with painstaking studio work, but complain that he became obsessive to the irksome point where he felt simultaneously indispensable and undervalued. Beyond even-handed analysis, they sometimes shout "Wanker!" in his general direction. (Depeche Mode did not want Q to talk to him because they felt he might be "bitter": Q tried anyway, but Wilder, who is still signed to the band's label and publisher, Mute, said he "wasn't talking to anyone yet.") If that was a difficulty resolved, off-tour Gahan hit the skids. There was a "daily habit", a disintegrated second marriage, failed detoxes and a highly publicised suicide attempt.

"I was really scared. I wouldn't wish it on anyone - to go to that depth, to push yourself to a place of such...pain."

Occasionally apprised of these horrors, Gore wrote a batch of songs which, he retrospectively infers, address the theme of "trying to work life out and life never quite working", and led on to the co-option of Tim Simenon, the repairing to Electric Lady, Gahan's final speedball, and the recovery they all believe is for real.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

On pain of a two-year jail sentence for using any kind of illegal drug, Gahan submitted to random urine testing. He attended the Los Angeles Exodus Clinic (cautionarily deceased alumni, Kurt Cobain and Blind Melon's Shannon Hoon). He completed the full rehab programme. He even submitted to the vocal coaching his colleagues urged on him.

"His vocals on this record are fantastic," enthuses Fletcher. "When Dave was ill some people were asking why we couldn't get rid of him, get another singer. But Dave would never come to me and say, Gore's being a pain, let's get another songwriter. His voice and Mart's songs are Depeche Mode.

"If Dave had died last May, I wouldn't have felt guilty that I didn't do enough for him. He knew exactly what he was up to and I did as much as I could. But now, after what I've been through, if he's feeling depressed - he's waiting for news about his divorce from Teresa - he can talk to me, and I can help him. He realises that I've suffered similar pains to him. Although I know Dave's volatile and he's got a lot on his plate, I hope he's going to be an inspiration, a success story."

Considering his prognosis for the singer, Gore is positive but less gung-ho than Fletcher.

"Dave is a changed person. If he started using again we would know immediately," he claims. "I'm sure it's actually helped him to have a jail sentence hanging over his head, although it's horrible to say it. He will have to stay on a path of total abstinence, because the moment he has a drink his inhibitions come down and he's off scoring."

While backing Fletcher's plan not to play live for the next six months and possibly not at all this year, Gore says he can't shake off a malaise which began long before those difficult '90s.

"Since Black Celebration (1986), I've felt our set-up could fall apart at any time. I still feel that. Hopefully, we'll get through the next six months unscathed. But you never can tell."

In darker moments, Gahan reflects that Gore and Fletcher must feel they can no longer rely on him long term.

"I put them through a lot of worry. I'm sure they think I won't last."

Nonetheless, he's always encouraged by the uncanny empathy between himself and Gore's songs. As usual, listening to the Ultra demos, Gahan felt that the lyrics had been tailored to fit his personality and his life - the love, the drugs, the lot - although Gore has told him many times that this is simply not so."

"Well, it's good Dave thinks the songs are hand-crafted for him," decides Gore. "It enables him to give his all performing them. I suppose the illusion comes from our similar upbringings and all the years together in the band. But I never try to write from Dave's perspective. I don't think it's possible to write truthfully from another person's point of view."

Then what is the truth behind the quiet public demeanour and the faintly silly image - the childish apple cheeks, funny hairdo, louche leathers - which deflect recognition from the strength and constancy of one of British pop's most consistent and innovative writers?

"Obviously, my working-class background has an effect on me (his father worked at Ford's, Dagenham). But politics is a fraction of what I think about. Religion comes up constantly in my songs, but always in terms of questioning. To me, it's the crux of life - what is the point to all this? If there's nothing beyond birth and death, it seems futile. I'd like to think there's a grander scheme. I do believe in some higher being, some form of spirituality, but that's as far as it goes.

"I know I have my crutches - I drink too much, still - but I think maybe that the most important thing in me is I've got a love affair with life. The other day I was trying to think of one person, I mean any person, who I dislike and I couldn't. Which is positive, but terribly naive. I'm sure there are a lot of people out there that I absolutely adore who hate me."

"His vocals on this record are fantastic," enthuses Fletcher. "When Dave was ill some people were asking why we couldn't get rid of him, get another singer. But Dave would never come to me and say, Gore's being a pain, let's get another songwriter. His voice and Mart's songs are Depeche Mode.

"If Dave had died last May, I wouldn't have felt guilty that I didn't do enough for him. He knew exactly what he was up to and I did as much as I could. But now, after what I've been through, if he's feeling depressed - he's waiting for news about his divorce from Teresa - he can talk to me, and I can help him. He realises that I've suffered similar pains to him. Although I know Dave's volatile and he's got a lot on his plate, I hope he's going to be an inspiration, a success story."

Considering his prognosis for the singer, Gore is positive but less gung-ho than Fletcher.

"Dave is a changed person. If he started using again we would know immediately," he claims. "I'm sure it's actually helped him to have a jail sentence hanging over his head, although it's horrible to say it. He will have to stay on a path of total abstinence, because the moment he has a drink his inhibitions come down and he's off scoring."

While backing Fletcher's plan not to play live for the next six months and possibly not at all this year, Gore says he can't shake off a malaise which began long before those difficult '90s.

"Since Black Celebration (1986), I've felt our set-up could fall apart at any time. I still feel that. Hopefully, we'll get through the next six months unscathed. But you never can tell."

In darker moments, Gahan reflects that Gore and Fletcher must feel they can no longer rely on him long term.

"I put them through a lot of worry. I'm sure they think I won't last."

Nonetheless, he's always encouraged by the uncanny empathy between himself and Gore's songs. As usual, listening to the Ultra demos, Gahan felt that the lyrics had been tailored to fit his personality and his life - the love, the drugs, the lot - although Gore has told him many times that this is simply not so."

"Well, it's good Dave thinks the songs are hand-crafted for him," decides Gore. "It enables him to give his all performing them. I suppose the illusion comes from our similar upbringings and all the years together in the band. But I never try to write from Dave's perspective. I don't think it's possible to write truthfully from another person's point of view."

Then what is the truth behind the quiet public demeanour and the faintly silly image - the childish apple cheeks, funny hairdo, louche leathers - which deflect recognition from the strength and constancy of one of British pop's most consistent and innovative writers?

"Obviously, my working-class background has an effect on me (his father worked at Ford's, Dagenham). But politics is a fraction of what I think about. Religion comes up constantly in my songs, but always in terms of questioning. To me, it's the crux of life - what is the point to all this? If there's nothing beyond birth and death, it seems futile. I'd like to think there's a grander scheme. I do believe in some higher being, some form of spirituality, but that's as far as it goes.

"I know I have my crutches - I drink too much, still - but I think maybe that the most important thing in me is I've got a love affair with life. The other day I was trying to think of one person, I mean any person, who I dislike and I couldn't. Which is positive, but terribly naive. I'm sure there are a lot of people out there that I absolutely adore who hate me."

[1] - Ominously, this was the very same hotel where Dave overdosed on the night of 27th/28th May 1996.

- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

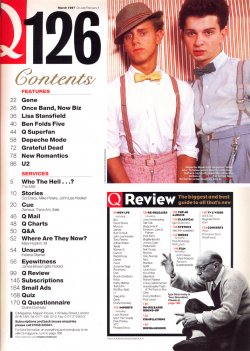

Q

Date: March 1997

Description: Mars 1997, N°126

Pays: Royaume-Uni

Date: March 1997

Description: Mars 1997, N°126

Pays: Royaume-Uni

Attachments

-

0a.jpg958.1 KB · Views: 391

0a.jpg958.1 KB · Views: 391 -

0b.jpg724.1 KB · Views: 325

0b.jpg724.1 KB · Views: 325 -

1.jpg970.1 KB · Views: 590

1.jpg970.1 KB · Views: 590 -

2.jpg1,014.1 KB · Views: 312

2.jpg1,014.1 KB · Views: 312 -

3.jpg909.7 KB · Views: 338

3.jpg909.7 KB · Views: 338 -

4.jpg812.3 KB · Views: 1,155

4.jpg812.3 KB · Views: 1,155 -

5.jpg895.1 KB · Views: 406

5.jpg895.1 KB · Views: 406 -

6.jpg858.2 KB · Views: 335

6.jpg858.2 KB · Views: 335 -

7.jpg785.2 KB · Views: 426

7.jpg785.2 KB · Views: 426 -

8.jpg860.7 KB · Views: 316

8.jpg860.7 KB · Views: 316 -

9.jpg889.9 KB · Views: 418

9.jpg889.9 KB · Views: 418 -

10.jpg746.9 KB · Views: 336

10.jpg746.9 KB · Views: 336