UNSOUND RECORDINGS

[Sound On Sound, January 1998. Words: Bill Bruce/ Pictures: Uncredited.]

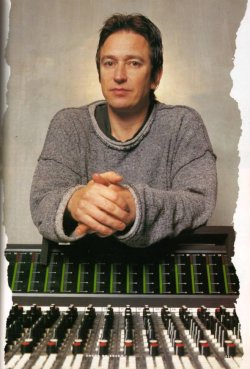

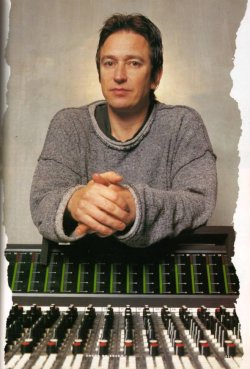

For many of us a home studio is a loft or bedroom crammed – if we’re lucky – with a sampler, synth, computer, some effects and a DAT player. Alan Wilder, late of Depeche Mode and currently working on a studio-based recording project titled Recoil, may have a home studio somewhat grander than most, but he maintains that his setup is surprisingly simple. The main work area was actually planned by an interior design company, and consequently exhibits the same exquisite, minimalist, open-plan design as his family home (as you can see from the pictures accompanying this article). The studio is not divided into a control room and a live room; in fact the main studio floor has no dividers or acoustic booths of any kind. This was a conscious decision on Alan’s part intended to meet his own methodology:

“It’s important for me to have space. Both at home and in the studio. This place was never designed to have a controlled sound or environment like a traditional studio, but rather to have the feel of a workshop, with plenty of light and space.”

POP WILL EAT ITSELF

As though some perverse inverse square law is at work, the amount of light and space in this amazing home studio appears in total contrast to the sound of the new Recoil album Unsound Methods, which is a densely-plotted, dark and atmospheric work. It’s all quite some way from Wilder’s work with Depeche Mode, with whom he shot to fame in the ‘80s. Answering an anonymous group’s Melody Maker Wanted ad for a keyboard player in 1981, Alan was fairly surprised to find himself in Depeche Mode, replacing Vince Clarke (until this point the chief songwriter in the band), who had just left the group. Songwriting duties in Depeche were subsequently taken over by Martin Gore, and Wilder became responsible for programming, sound design and production in the group as time went on, leaving no outlet for his own musical compositions; a handful were released on Depeche Mode B-sides or as the very occasional low-key album track, but that was all. It is now tempting to view Wilder’s solo project Recoil, which he launched in 1986, as his way of musically letting off steam from Depeche Mode, but as he explains, the idea of the frustrated composer desperately struggling to find an outlet for his darker musical outpourings while operating day-to-day in a hugely successful pop band somewhat belies the true, much more casual origins of the Recoil project. Admittedly, since his well-documented split from Depeche a couple of years ago, Recoil has become the focus for Wilder’s creative energies, becoming a one-man musical melting pot which has so far managed to mix blues, rock, electronics, classical elements, ambient and rap (and that’s just for starters). But in the beginning, there was just a collection of tracks released in the mid-80’s, titled (with typical minimalism) 1+2: just a home demo which hadn’t even been intended to lead anywhere in particular.

Wilder: “1+2 was really just me mucking around at home. It was a cassette demo on a 4-track Fostex or Tascam, and only ended up being released after I played it to Daniel [Miller, Managing Director of Mute Records, Depeche Mode’s independent record label]. He said, ‘could you re-do this?’ I didn’t really have time to do it properly, so we just decided to release it inconspicuously, as it was, and not pay too much attention to it.”

The modest success of 1+2 led Wilder to release a more ambitious follow-up three years later. 1989’s Hydrology was still a far cry from the commercial pop sound of Wilder’s day job, however. It remained entirely instrumental, and was still recorded on a fairly modest setup. “Hydrology was a step up from 1+2. It was done on a half-inch 16-track Fostex machine. So there were limitations, but it was much more versatile than the first thing I had done. Recoil was still very much an aside to Depeche Mode, with no pressure or expectations placed upon it. In other words, it wasn’t my main concern, and was always going to be an ‘antidote’ to Depeche Mode in some ways; a way to alleviate the frustrations of always working within a pop format. I have nothing against the pop format, but if I was going to do something on my own, there was no point in repeating what I was already doing in the group. It was intended to be completely different and experimental. It didn’t matter if it was too left-field or too weird for people, because I was still doing the pop thing on the other side.”

However, it could be argued that Bloodline, released in 1991, was a much more commercial effort. With vocals from Douglas McCarthy of Nitzer Ebb, Toni Halliday of Curve, and Moby, it came closer to having actual songs, albeit songs which split and divided with alarming regularity. For Wilder, though there was no conscious attempt to change: “I certainly didn’t feel a pressure to make it more conventional, but I did feel that I couldn’t just keep producing experimental instrumental music all the time.”

“I’d quite often get to a stage where I thought the music lacked something, and reasoned that if I was to progress with it in any way, I would have to bring something else in – be it vocals or whatever – to enhance what were basically backing tracks. Bloodline was a halfway-house between the early stuff and what I’m doing now. I brought the vocals in, but I didn’t really see it through in the way I should have done; I think I lacked the energy. I had Depeche Mode commitments, and I was really fitting Bloodline into the first real break the band had taken in 10 years.

“By the end of that year – while also producing a Nitzer Ebb album – I’d just run out of energy. I think the album suffers a little bit because of it, especially the vocals. They’re there as almost last-minute atmospherics rather than to make real songs.”

[Sound On Sound, January 1998. Words: Bill Bruce/ Pictures: Uncredited.]

An immense, studio-oriented article examining Alan Wilder's work, especially in the light of the Unsound Methods album being released at the time. Alan talks intelligently and in detail about his recording practices and general musical outlook as well as some technical talk. To his and the author's credit, his time in Depeche Mode is discussed from a personal viewpoint rather than becoming swallowed by general band history. Porno for musos.

" To me, the details are very important, and I’m not content with guitar, bass and drums as my only instrumentation. If you’ve got the possibility to refine your music by bringing in a variety of atmospheres and textures, then why not do it? You can draw people into the music even though all the little details don’t really make themselves apparent right away. "

For many of us a home studio is a loft or bedroom crammed – if we’re lucky – with a sampler, synth, computer, some effects and a DAT player. Alan Wilder, late of Depeche Mode and currently working on a studio-based recording project titled Recoil, may have a home studio somewhat grander than most, but he maintains that his setup is surprisingly simple. The main work area was actually planned by an interior design company, and consequently exhibits the same exquisite, minimalist, open-plan design as his family home (as you can see from the pictures accompanying this article). The studio is not divided into a control room and a live room; in fact the main studio floor has no dividers or acoustic booths of any kind. This was a conscious decision on Alan’s part intended to meet his own methodology:

“It’s important for me to have space. Both at home and in the studio. This place was never designed to have a controlled sound or environment like a traditional studio, but rather to have the feel of a workshop, with plenty of light and space.”

POP WILL EAT ITSELF

As though some perverse inverse square law is at work, the amount of light and space in this amazing home studio appears in total contrast to the sound of the new Recoil album Unsound Methods, which is a densely-plotted, dark and atmospheric work. It’s all quite some way from Wilder’s work with Depeche Mode, with whom he shot to fame in the ‘80s. Answering an anonymous group’s Melody Maker Wanted ad for a keyboard player in 1981, Alan was fairly surprised to find himself in Depeche Mode, replacing Vince Clarke (until this point the chief songwriter in the band), who had just left the group. Songwriting duties in Depeche were subsequently taken over by Martin Gore, and Wilder became responsible for programming, sound design and production in the group as time went on, leaving no outlet for his own musical compositions; a handful were released on Depeche Mode B-sides or as the very occasional low-key album track, but that was all. It is now tempting to view Wilder’s solo project Recoil, which he launched in 1986, as his way of musically letting off steam from Depeche Mode, but as he explains, the idea of the frustrated composer desperately struggling to find an outlet for his darker musical outpourings while operating day-to-day in a hugely successful pop band somewhat belies the true, much more casual origins of the Recoil project. Admittedly, since his well-documented split from Depeche a couple of years ago, Recoil has become the focus for Wilder’s creative energies, becoming a one-man musical melting pot which has so far managed to mix blues, rock, electronics, classical elements, ambient and rap (and that’s just for starters). But in the beginning, there was just a collection of tracks released in the mid-80’s, titled (with typical minimalism) 1+2: just a home demo which hadn’t even been intended to lead anywhere in particular.

Wilder: “1+2 was really just me mucking around at home. It was a cassette demo on a 4-track Fostex or Tascam, and only ended up being released after I played it to Daniel [Miller, Managing Director of Mute Records, Depeche Mode’s independent record label]. He said, ‘could you re-do this?’ I didn’t really have time to do it properly, so we just decided to release it inconspicuously, as it was, and not pay too much attention to it.”

The modest success of 1+2 led Wilder to release a more ambitious follow-up three years later. 1989’s Hydrology was still a far cry from the commercial pop sound of Wilder’s day job, however. It remained entirely instrumental, and was still recorded on a fairly modest setup. “Hydrology was a step up from 1+2. It was done on a half-inch 16-track Fostex machine. So there were limitations, but it was much more versatile than the first thing I had done. Recoil was still very much an aside to Depeche Mode, with no pressure or expectations placed upon it. In other words, it wasn’t my main concern, and was always going to be an ‘antidote’ to Depeche Mode in some ways; a way to alleviate the frustrations of always working within a pop format. I have nothing against the pop format, but if I was going to do something on my own, there was no point in repeating what I was already doing in the group. It was intended to be completely different and experimental. It didn’t matter if it was too left-field or too weird for people, because I was still doing the pop thing on the other side.”

However, it could be argued that Bloodline, released in 1991, was a much more commercial effort. With vocals from Douglas McCarthy of Nitzer Ebb, Toni Halliday of Curve, and Moby, it came closer to having actual songs, albeit songs which split and divided with alarming regularity. For Wilder, though there was no conscious attempt to change: “I certainly didn’t feel a pressure to make it more conventional, but I did feel that I couldn’t just keep producing experimental instrumental music all the time.”

“I’d quite often get to a stage where I thought the music lacked something, and reasoned that if I was to progress with it in any way, I would have to bring something else in – be it vocals or whatever – to enhance what were basically backing tracks. Bloodline was a halfway-house between the early stuff and what I’m doing now. I brought the vocals in, but I didn’t really see it through in the way I should have done; I think I lacked the energy. I had Depeche Mode commitments, and I was really fitting Bloodline into the first real break the band had taken in 10 years.

“By the end of that year – while also producing a Nitzer Ebb album – I’d just run out of energy. I think the album suffers a little bit because of it, especially the vocals. They’re there as almost last-minute atmospherics rather than to make real songs.”