You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

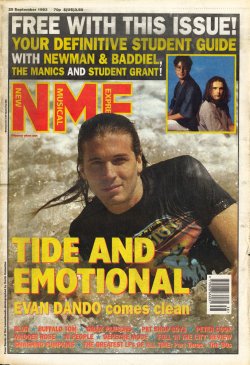

Depeche Mode Tattoo Unlimited (NME, 1993)

- Thread starter demoderus

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1993 nme tattoo unlimited

Second article of an excellent two-parter behind the scenes with Depeche Mode in Hungary. Here, Dave comes close to breaking the world record for the longest unhindered spouting of complete tripe, as the writer allows Dave's own words to lay bare his mental state at the time. Contrasted with a fan's intelligent reflections on the band's appeal and the murmurings of the Mode's tour officialdom, this makes for sordid and harrowing reading.

" I’ve actually got lots and lots of friends now. I spend a lot of time with my friends. It’s something I’d forgot how to do, I think I sort of really isolated myself, not even intentionally but… over the years I had. Now I’ve made a lot of really, really good friends, good people. "

Return to the manor of the Rock Gods! In the second instalment of the touring madness that is DEPECHE MODE’s Hungarian foray, GAVIN MARTIN gets that inking feeling while DAVID GAHAN gets the needle down at the tattoo parlour, returns to “scary” Basildon, opens up to his audience, and considers the future of the Mode. And that’s before the live sex party in London gets swinging…

Depeche Mode are gathered back at their hotel bar – base camp for their three days in Hungary. They’ve played their game of table football, watched by the girls and boys backstage, after the gig. Now it’s time to fuel up with some more juice before hitting the town – a grubby little disco bar in a backwater of Budapest.

Andy Fletcher has thrown caution, and Yoga tea, to the wind and is taking his chances with a sizeable draught of lager. The last time Fletcher was interviewed by the NME the journalist started out by asking if he drank a lot on the road. The press officer was livid: sat behind the journalist, he started signalling to Fletcher to terminate the interview. The subsequent feature was given as the reason why the band refused to meet NME for many months. [1]

They had finally decided to talk to the paper earlier this year, but when we ran a vintage 1985 Depeche Mode feature in our Rock Of Ages series they thought we were “taking the piss” and the whole thing was put back again. A touchy lot, pop stars.

Martin Gore is staving off one of his panic attacks by blagging a Nurofen off a girl from his record company. Soon he’ll be off charging round the bar, playing piggyback fights until he falls off his carrier’s back. The tequila slammer-fuelled horseplay was always heading that way, building up to a peak.

“Is it always like this?” gasps the serious young Hungarian girl when Gore fell over.

“I’m bleeding, I’m bleeding,” screamed Gore still lying on his back.

Concerned faces peered down at the little blond stick-man. Then he leapt up with a cheeky grin on his face. He wasn’t bleeding at all, and he was ready for another tequila slammer. And so the romp continued.

David Gahan made a brief appearance before retiring early. Unlike the others, he had early-morning video-shoot duties to perform. Gahan sat at a table where someone was discussing the concept of Political Correctness. “What’s that?” he asked. The PC ideal was duly explained to him. “Hmmm, sounds really boring,” said The Thin One before sloping off to his lair.

Alan Wilder is described by some as the Keith Richards of the band, meaning he sculpts the sound of their records with producer Flood, fills out the Depeche canvas, gives vital tension, drama and atmosphere to Martin Gore’s potentially morbid ditties. These days, ten years ahead of schedule, he is also taking on the appearance of the latter-day Sir Keef. Wilder by name, Wilder by nature – knocking back double tequila shots and his face is becoming a well-worn road map of rock’n’roll excess.

Judith, the serious young Hungarian girl, had got short shrift when she approached Alan Wilder earlier with an enquiry about his band, and she’d taken an instant dislike to him. Judith was the only person that spoke English among her group of friends. She’d been able to get into the band’s hotel because she’d been working at their show, voluntarily handing out AIDS awareness leaflets in a tent pitched at the back of the stadium.

She wasn’t interested in the band the way the other little girls with stockings and suspenders and “F--- me” T-shirts were, but Judith wanted to talk to Depeche because she’d invested a lot of time in their music. She and her friends had hired out a big civic hall in Budapest once every month for almost six years. Drawing between 1500 and 2000 fans each month, this was the biggest Depeche convention in Budapest, though there were smaller ones held in smaller venues every week. Depeche nights had become the rallying point for Judith and her friends during their teenage years, providing food, drink, Depeche chat, Depeche stories, Depeche records.

It was a phenomenon that had outlasted even the Russian empire collapse of the late ’80s. Now as those momentous changes were still having their effect, Judith and her friends were more conscious than ever that Hungary was at a crossroads. They watched events unfold across the border in Yugoslavia with considerable trepidation. They knew about the refugee problem, the camps outside of Budapest packed with people on the run from the war.

“It won’t happen here,” I was told later by the young Hungarian outside the hotel, “we’re good people, we don’t want a war.” You had to hope they were right, but it was only 50 years ago, during the Nazi occupation, that the local Jewish population were drowned in the Danube, the river that runs through Budapest. Dominated by the Nazis, then the Russians, Hungary was a country where it must have been hard to hold on to – or even to find – something to believe in. Things were moving again in this part of the world, heading in a dangerous direction, and for these young people the future wasn’t clear. Maybe that’s why they still held their Depeche devotion dear.

It was a hard thing to explain, a hard thing to understand what Depeche Mode meant here, Judith explained, but it was something special, something that the band’s followers elsewhere might be surprised by. The Depeche club was now something that had become bigger than the band, lots of kids with problems, dysfunctional kids, kids with backgrounds not unlike David Gahan’s, in fact, from delinquent backgrounds and broken homes had come together at these nights. Depeche Mode was the common link that had provided a spur – helping the kids discover themselves, to forge their own identity and develop relationships with like-minded souls.

Why did Depeche Mode, out of all the bands who made music during the ’80s, mean so much to these young Hungarians? Obviously their imagery and sound was immediately recognisable as European, breaking with the Anglo-American pop hegemony. But it was more than that. Judith said that Martin Gore’s songs discussed things that often go unspoken, problems and fears that are usually hidden away. She said she’d always cherish the times at the club and the friends she’d made there, that Depeche Mode meant something much more to her than a pop band.

[1] - I've a feeling the article being referred to is this one, although what's published appears pretty inoffensive to me.

Last edited:

Judith started to feel embarrassed. Her boyfriend kept goading her to go and ask some serious questions of Martin or Andy. But neither of them seemed to be in any mood to talk in great depth at this time of the night. So she bided her time and watched them.

She reckoned that Fletch was the nicest, the most approachable. She thought that Martin Gore wasn’t being his natural self, that he was putting on a rock-star tour-madness act because it was what was expected of him. She was repelled by Alan Wilder, he looked dreadful and she didn’t think it was right the way he was messing round with the young girls at the bar. When he left the hotel for more tequila at the disco club, a group of Hungarian fans clambered outside at the window. Wilder staggered up towards them. “Go on, f--- off!” he said. “Get away from the f---ing window.”

And then there was David Gahan.

The Depeche club were worried about David. They knew he had problems, you didn’t need to see him up close for too long to see that. They’d read about them in interviews, and they thought that Martin Gore had tried to help him with the songs he’d written for the new LP – they heard them as gifts from a friend, prayers for help and forgiveness. But David still didn’t look well. They hoped that he would get better, they didn’t want him to be a martyr for their religion.

Back at the hotel at 5am, after a few hours at Dull Disco, there was still a tribe of Depeches camped at the door. The girls were all dressed in black sackcloth, some carrying posters and some carrying scrapbooks of Depeche trivia. One kid, a gypsy crustie type had matted hair, rings of dirt round her face and the words “punk forever” on her baseball boots. Some of the boys brandished home-made Depeche passes, favouring an archive colour group shot from 1987 bound up in card and sticky tape. They wanted me to bring David Gahan down to see them. All they wanted was a hello. They’d been waiting there all day – couldn’t I just tap on his door and ask? Surely he couldn’t refuse, they reasoned.

Why Depeche Mode, I wondered, what’s the big thing with them? They told me that it’s all to do with the sadness, that Depeche Mode music doesn’t ignore sadness, that it puts sadness at its centre and recognises that sadness is the most common experience in the world, something everyone can relate to.

It wasn’t a cheery note on which to say goodnight and it probably wasn’t what David Gahan, 20 floors above and three hours away from his video shoot, wanted to hear.

Back in his dressing room earlier the previous evening, Gahan considered what he’d be doing if he wasn’t the object of the kids’ affections, if he wasn’t a singer.

“I’d be a mass murderer or something like that,” he laughs. “That’s not really true. Y’know what? Even when I was a little kid… I swear when I was a little kid I used to walk to school and try and miss every crack in the pavement. I know everybody’s done this but my thing was I was just going to do something and all this school crap could f--- off. Because I hated school, from day one I wanted to get out of there, y’know, I really hated it. So I just knew I was going to do something else.

“Compared to my other mates I didn’t fit in very well with any kind of… I moved around a lot, put it that way. I had a lot of mates, a lot of people I could go to hang out with that I could pick for different sorts of moods. Violent ones, druggy ones, just girls.”

You had a criminal record before you put out a record…

“Don’t bring that up again, I have enough trouble trying to get in and out of places as it is.”

When you jumped into the audience last week, did you know no fear?

“That’s the whole point. I learned that in Mannheim when I accidentally did it. I thought, if I’m going to do it, I’m really going to do it, I’m going to do it as if I’m diving off the top board at Basildon at 16 at Oswald Park swimming pool. Me and my mate Jay used to dive off the top, get up enough courage to dive off that top board. You just go, YES! Somebody’s going to pick you up, they can rip you apart but they eventually will put you back up.

“You feel it, it’s scary, it’s a weird thing with all these hands, a million hands all over you, pulling you, and you see faces and suddenly you see someone like one of our security guards and they’re like, ‘Dave, we got you’. They ripped my shirt off, it was really funny. If they’d done it tonight there was no way I’d have got out, no way. I’m not that strong.”

How do you feel about your audience? You must have mixed feelings.

“I hate the ones that try to be cool – we’re going to have a good time but stand back. That English thing, y’know. I think in general they’ve been right with us all the way. It gets a little bit more every time, little steps.”

Do you wonder how you’ll relate to a new, younger generation of Depeche fans?

“The only way I think about that is because I have a son. And I feel although I don’t really have any responsi… My son is with my ex-wife. Anyway… so anyway, but I still feel responsibility of the fact that I would want him to be… to see everything, to experience things, to make up his own mind. I think that’s something I’ve learned through touring around with Depeche Mode because I had f--- all education at school, apart from that I could paint. Everything else was just boring.”

You said earlier that you don’t like interviews.

“It’s not so much that. I like talking to people, it’s what it gets turned into. You try to be open with people and just talk and sometimes you might go a little bit off because maybe you’re trying to feel in a different mood to what you just felt. I can’t really explain that.”

You were talking about your divorce in interviews earlier this year. Doesn’t it annoy you that you have to do that? Surely it’s nobody’s business.

“Now I feel like that – and if you ask me any questions about that, I’d have to say that, and I know you’d respect that. I obviously had to talk about some stuff so I think it helped me a lot, in some way… I hope it didn’t hurt Joanne.”

You didn’t get much education, but you’ve become a pop star. Do you have to learn how to do that?

“Yeah, you do. I’m getting really good at it now (laughs). No, the best thing about it for me now is I know we’ve made a really brilliant record, I feel really proud of it. I think “Violator” was the first step to what “Songs Of Faith And Devotion” achieved, the band starting to work together a lot more to get some emotion from things that maybe weren’t there when, say, Martin just wrote the songs. Alan and I would work very hard to just build things, we’re really into atmospheres and stuff.

“It’s not just, Martin writes a song and that’s it. I mean he loves Neil Young and I love Neil Young too, but… I’m not putting Martin down in any way… it’s just that after he’s written it he thinks he’s done what he has to do.”

Do you share the writing credit?

“Naw… It’s just Martin.”

Doesn’t that annoy you? I couldn’t imagine many people wanting to listen to a Gore song before it’s been through the Mode machine.

“Umm, I sort of felt with this album that it was a little bit unfair. Not because Martin didn’t write all the songs. He wrote the songs and they’re brilliant songs and… umm. Y’know, everything came from him, but everybody else also worked really hard to really put some real emotion down. Alan would stay there forever, basically. I was just trying to feel much more than I’d ever felt about words and melodies and highs and lows.”

She reckoned that Fletch was the nicest, the most approachable. She thought that Martin Gore wasn’t being his natural self, that he was putting on a rock-star tour-madness act because it was what was expected of him. She was repelled by Alan Wilder, he looked dreadful and she didn’t think it was right the way he was messing round with the young girls at the bar. When he left the hotel for more tequila at the disco club, a group of Hungarian fans clambered outside at the window. Wilder staggered up towards them. “Go on, f--- off!” he said. “Get away from the f---ing window.”

And then there was David Gahan.

The Depeche club were worried about David. They knew he had problems, you didn’t need to see him up close for too long to see that. They’d read about them in interviews, and they thought that Martin Gore had tried to help him with the songs he’d written for the new LP – they heard them as gifts from a friend, prayers for help and forgiveness. But David still didn’t look well. They hoped that he would get better, they didn’t want him to be a martyr for their religion.

Back at the hotel at 5am, after a few hours at Dull Disco, there was still a tribe of Depeches camped at the door. The girls were all dressed in black sackcloth, some carrying posters and some carrying scrapbooks of Depeche trivia. One kid, a gypsy crustie type had matted hair, rings of dirt round her face and the words “punk forever” on her baseball boots. Some of the boys brandished home-made Depeche passes, favouring an archive colour group shot from 1987 bound up in card and sticky tape. They wanted me to bring David Gahan down to see them. All they wanted was a hello. They’d been waiting there all day – couldn’t I just tap on his door and ask? Surely he couldn’t refuse, they reasoned.

Why Depeche Mode, I wondered, what’s the big thing with them? They told me that it’s all to do with the sadness, that Depeche Mode music doesn’t ignore sadness, that it puts sadness at its centre and recognises that sadness is the most common experience in the world, something everyone can relate to.

It wasn’t a cheery note on which to say goodnight and it probably wasn’t what David Gahan, 20 floors above and three hours away from his video shoot, wanted to hear.

Back in his dressing room earlier the previous evening, Gahan considered what he’d be doing if he wasn’t the object of the kids’ affections, if he wasn’t a singer.

“I’d be a mass murderer or something like that,” he laughs. “That’s not really true. Y’know what? Even when I was a little kid… I swear when I was a little kid I used to walk to school and try and miss every crack in the pavement. I know everybody’s done this but my thing was I was just going to do something and all this school crap could f--- off. Because I hated school, from day one I wanted to get out of there, y’know, I really hated it. So I just knew I was going to do something else.

“Compared to my other mates I didn’t fit in very well with any kind of… I moved around a lot, put it that way. I had a lot of mates, a lot of people I could go to hang out with that I could pick for different sorts of moods. Violent ones, druggy ones, just girls.”

You had a criminal record before you put out a record…

“Don’t bring that up again, I have enough trouble trying to get in and out of places as it is.”

When you jumped into the audience last week, did you know no fear?

“That’s the whole point. I learned that in Mannheim when I accidentally did it. I thought, if I’m going to do it, I’m really going to do it, I’m going to do it as if I’m diving off the top board at Basildon at 16 at Oswald Park swimming pool. Me and my mate Jay used to dive off the top, get up enough courage to dive off that top board. You just go, YES! Somebody’s going to pick you up, they can rip you apart but they eventually will put you back up.

“You feel it, it’s scary, it’s a weird thing with all these hands, a million hands all over you, pulling you, and you see faces and suddenly you see someone like one of our security guards and they’re like, ‘Dave, we got you’. They ripped my shirt off, it was really funny. If they’d done it tonight there was no way I’d have got out, no way. I’m not that strong.”

How do you feel about your audience? You must have mixed feelings.

“I hate the ones that try to be cool – we’re going to have a good time but stand back. That English thing, y’know. I think in general they’ve been right with us all the way. It gets a little bit more every time, little steps.”

Do you wonder how you’ll relate to a new, younger generation of Depeche fans?

“The only way I think about that is because I have a son. And I feel although I don’t really have any responsi… My son is with my ex-wife. Anyway… so anyway, but I still feel responsibility of the fact that I would want him to be… to see everything, to experience things, to make up his own mind. I think that’s something I’ve learned through touring around with Depeche Mode because I had f--- all education at school, apart from that I could paint. Everything else was just boring.”

You said earlier that you don’t like interviews.

“It’s not so much that. I like talking to people, it’s what it gets turned into. You try to be open with people and just talk and sometimes you might go a little bit off because maybe you’re trying to feel in a different mood to what you just felt. I can’t really explain that.”

You were talking about your divorce in interviews earlier this year. Doesn’t it annoy you that you have to do that? Surely it’s nobody’s business.

“Now I feel like that – and if you ask me any questions about that, I’d have to say that, and I know you’d respect that. I obviously had to talk about some stuff so I think it helped me a lot, in some way… I hope it didn’t hurt Joanne.”

You didn’t get much education, but you’ve become a pop star. Do you have to learn how to do that?

“Yeah, you do. I’m getting really good at it now (laughs). No, the best thing about it for me now is I know we’ve made a really brilliant record, I feel really proud of it. I think “Violator” was the first step to what “Songs Of Faith And Devotion” achieved, the band starting to work together a lot more to get some emotion from things that maybe weren’t there when, say, Martin just wrote the songs. Alan and I would work very hard to just build things, we’re really into atmospheres and stuff.

“It’s not just, Martin writes a song and that’s it. I mean he loves Neil Young and I love Neil Young too, but… I’m not putting Martin down in any way… it’s just that after he’s written it he thinks he’s done what he has to do.”

Do you share the writing credit?

“Naw… It’s just Martin.”

Doesn’t that annoy you? I couldn’t imagine many people wanting to listen to a Gore song before it’s been through the Mode machine.

“Umm, I sort of felt with this album that it was a little bit unfair. Not because Martin didn’t write all the songs. He wrote the songs and they’re brilliant songs and… umm. Y’know, everything came from him, but everybody else also worked really hard to really put some real emotion down. Alan would stay there forever, basically. I was just trying to feel much more than I’d ever felt about words and melodies and highs and lows.”

Last edited:

Had you felt disaffected in the past?

“I felt… I just kicked myself in the arse and said, ‘What do you really wanna do, what are you really like? Pick, y’know? What do you want? Do you want the big fancy house in the country with loads of cars or do you wanna go somewhere and just live with people and just hang out and stuff like that?’

“That’s me now, y’know? Now I’ve got enough space to really get into music, not thinking about that kind of stuff, like, ahh, ‘I wonder if I can, like, buy a car’ or something. What would I want to think about shit like that any more for?”

Is being on tour still a helter-skelter experience for you, emotional highs followed by depressing lows?

“Totally, yeah. I mean, you’re lucky you’re here, really. I might have just been saying, ‘Tell him I don’t want to f---ing do it, tell him I’m ill’. I’m really high from the f---ing gig, y’know, it’s… When it’s like that…

“I won’t even sleep tonight. I’ve got to get up and go and do some… I’ve got to go off with (Anton) Corbijn into the f---ing woods and do the ‘Condemnation’ bit. [1] But, really, I have fun with doing that. It’s just the eight o’clock morning, you gotta get over it.”

You say you changed everything about yourself. The first thing people say is you changed the way you look. Is it more than that?

“I don’t think I even… It’s funny, you know, ’cos I know my hair got long, stuff like that, but I’ve always had beards, played around with beards and stuff ever since, like, I could ever grow one to be quite honest.

“And then I just… it was just like I said, I put my brain into a lot of different things, like I went out and I went to clubs and I started listening to music again. And I started seeing bands and getting into a band and following them around and getting into that feeling. Bands like Jane’s (Addiction), that was mainly due to my wife, because she was working for ’em. Instead of me doing the gig, I would just be able to go to the gig and hang out. It was great, really.”

Was that like following The Clash round when you were a kid?

“Yeah, it was the same sort of thing, but it was the Damned with me. I didn’t get The Clash until I was a little older, on account of my education (laughs).”

When did you first get a tattoo?

“When I was 14 at Southend seafront, by a man called Clive. He’d a tattoo round his neck – ‘cut here’, with all the dots. He was like a sort of sailor guy, perfect. That one there…” [2]

He shows me one of the old-style, rough-and-ready designs.

“A collector’s item? Yeah they love it now, the people that work on me now, when they see this, it’s like, ‘Who done that?’ All these guys know each other, it’s a whole scene – in Amsterdam, f---ing Los Angeles, in London, in Japan it’s like they all know each other, it’s a real clan. Tattooists, they stick together. When they see this, they flip out – especially Bob, who done a lot of stuff on me, this guy called Bob Roberts from L.A.”

What was the last thing you had done?

“The last I had done was two weeks before I left. I had to have the first bit done and then it had to heal a bit and then I had to go and have the rest done. But I had to get it done, we’d drawn it and everything and so…

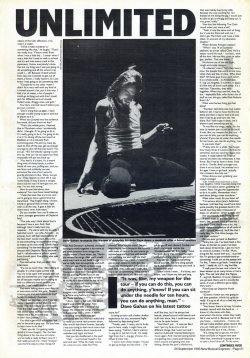

“It was like my wings, really, for the tour (a massive pair etched on his back). It was, like, my weapon for the tour – if you can do this, you can do anything, y’know? If you can sit under the needle for ten hours, you can do anything, man.”

It was sore, then?

“Pretty sore for a while. You forget how many times it’s nice to do that (he stretches), and you can’t for about two weeks. It really killed me. Then of course we went into rehearsals, it was funny. But I had to have it done, I had to do it. Charlie, Bob’s younger son, drew it on my back. He worked on it for ages. I have to go back, actually. He’s missed a few bits out.”

When did you start grabbing your crotch onstage?

“Oh, I think that goes back a long way (laughs). I think I started doing that when I was about seven, grabbing my crotch. Now I’ve got the opportunity to do it in public. Remember what I said about being a mass murderer.”

What other music do you listen to?

“I’m serious about Jane’s Addiction because I still feel they could have been quite possibly the greatest band in the world, but they blew it because of dope, or whatever, which is really sad.”

“I felt… I just kicked myself in the arse and said, ‘What do you really wanna do, what are you really like? Pick, y’know? What do you want? Do you want the big fancy house in the country with loads of cars or do you wanna go somewhere and just live with people and just hang out and stuff like that?’

“That’s me now, y’know? Now I’ve got enough space to really get into music, not thinking about that kind of stuff, like, ahh, ‘I wonder if I can, like, buy a car’ or something. What would I want to think about shit like that any more for?”

Is being on tour still a helter-skelter experience for you, emotional highs followed by depressing lows?

“Totally, yeah. I mean, you’re lucky you’re here, really. I might have just been saying, ‘Tell him I don’t want to f---ing do it, tell him I’m ill’. I’m really high from the f---ing gig, y’know, it’s… When it’s like that…

“I won’t even sleep tonight. I’ve got to get up and go and do some… I’ve got to go off with (Anton) Corbijn into the f---ing woods and do the ‘Condemnation’ bit. [1] But, really, I have fun with doing that. It’s just the eight o’clock morning, you gotta get over it.”

You say you changed everything about yourself. The first thing people say is you changed the way you look. Is it more than that?

“I don’t think I even… It’s funny, you know, ’cos I know my hair got long, stuff like that, but I’ve always had beards, played around with beards and stuff ever since, like, I could ever grow one to be quite honest.

“And then I just… it was just like I said, I put my brain into a lot of different things, like I went out and I went to clubs and I started listening to music again. And I started seeing bands and getting into a band and following them around and getting into that feeling. Bands like Jane’s (Addiction), that was mainly due to my wife, because she was working for ’em. Instead of me doing the gig, I would just be able to go to the gig and hang out. It was great, really.”

Was that like following The Clash round when you were a kid?

“Yeah, it was the same sort of thing, but it was the Damned with me. I didn’t get The Clash until I was a little older, on account of my education (laughs).”

When did you first get a tattoo?

“When I was 14 at Southend seafront, by a man called Clive. He’d a tattoo round his neck – ‘cut here’, with all the dots. He was like a sort of sailor guy, perfect. That one there…” [2]

He shows me one of the old-style, rough-and-ready designs.

“A collector’s item? Yeah they love it now, the people that work on me now, when they see this, it’s like, ‘Who done that?’ All these guys know each other, it’s a whole scene – in Amsterdam, f---ing Los Angeles, in London, in Japan it’s like they all know each other, it’s a real clan. Tattooists, they stick together. When they see this, they flip out – especially Bob, who done a lot of stuff on me, this guy called Bob Roberts from L.A.”

What was the last thing you had done?

“The last I had done was two weeks before I left. I had to have the first bit done and then it had to heal a bit and then I had to go and have the rest done. But I had to get it done, we’d drawn it and everything and so…

“It was like my wings, really, for the tour (a massive pair etched on his back). It was, like, my weapon for the tour – if you can do this, you can do anything, y’know? If you can sit under the needle for ten hours, you can do anything, man.”

It was sore, then?

“Pretty sore for a while. You forget how many times it’s nice to do that (he stretches), and you can’t for about two weeks. It really killed me. Then of course we went into rehearsals, it was funny. But I had to have it done, I had to do it. Charlie, Bob’s younger son, drew it on my back. He worked on it for ages. I have to go back, actually. He’s missed a few bits out.”

When did you start grabbing your crotch onstage?

“Oh, I think that goes back a long way (laughs). I think I started doing that when I was about seven, grabbing my crotch. Now I’ve got the opportunity to do it in public. Remember what I said about being a mass murderer.”

What other music do you listen to?

“I’m serious about Jane’s Addiction because I still feel they could have been quite possibly the greatest band in the world, but they blew it because of dope, or whatever, which is really sad.”

[1] - Some of the most telling moments in this interview are not in what Dave says, but what he shies away from saying - like just there.

[2] - This might be his oldest remaining, because I believe Dave's first (or at any rate one of the first) was removed in around 1981, with disastrous consequences. The skin unexpectedly bubbled up around the tattooed area, meaning he had to perform live with his arm in a sling. The burn-like marks are clearly visible on Dave's left forearm on pictures from the early Eighties, although he later had his "dagger" tattoo done over the area.

Are you friendly with Perry Farrell?

“I don’t want to get into that stuff, that’s, like, private, your private life. I like Nick Cave, the Stones a lot, my mate makes compilations of all kinds of stuff – Lynyrd Skynyrd. Stuff like that I really like, the Mid-West boogie, the old biker rockers.”

Do you ever go back to Basildon?

“Scary but, yes, I’ve been back a few times. In the last six years I’ve been back about three times. I get my mum to come to London. I’m like, ‘Mum, bring the flat round with you’. I just feel like I’m going to get arrested there or something. I walk out at the station and I’m like, ‘I want to go back, I want to go back’. I really do, it’s f---ing horrible.

“I walk past the taxi rank where I’ve been beaten up so many times or had a fight. The cab rank after the Mecca. F---ing hell, Basildon. It’s scary because you go back there and it’s exactly the same. It’s just a different generation. Very scary.”

How long can Depeche Mode continue?

“(Groans) I knew you were going to ask that question. I think it’s up to us, really. It’s up to all of us to feel we want to do it, of course.

“You know, there’s no way I’d make another record with the band or… I know it’s the same with Alan, everyone’s the same, unless they really felt it was worth it. Because we’re still, you know… everyone’s… I know we can make another great record. But you just really got to want to do it. I think after this tour if we, y’know…

“It’s a long way to go yet, we don’t finish until July or August next year. After that, everybody is going to want to take a lot of time off. To do some… just to go and y’know… aah.”

Have you ever been in a fist fight with anyone in the band?

“I actually haven’t, no. Fletch has had a fight with everyone but me. He’s never actually tried to hit me. But just lately I think he’s potentially been thinking about it.”

David doesn’t get the next question, my diction or my accent has him foxed.

“Where the f--- are you from?” he screams.

London, say I.

“But where is that accent from?”

Ireland, say I.

“But it’s mixed with London now. It’s just like Blade Runner, isn’t it?”

Eh?

“Soon there’s going to be another f---ing language everywhere. It’s getting hard to talk to people. What are they talking about?”

What do you like to do apart from music?

“I can’t wait to do the next thing, really. Aww, y’know, just… I’ve actually got lots and lots of friends now. I spend a lot of time with my friends. It’s something I’d forgot how to do, I think I sort of really isolated myself, not even intentionally but… over the years I had. Now I’ve made a lot of really, really good friends, good people. Mostly women, I may point out as well.”

That’s cool, it’s not illegal yet.

“Totally cool, especially when they’re all really good-looking as well.” (Cue hysterical schoolboy laughter of desperation)

It’s time to play that old game: I’ve-had-more-totty-than-you’ve-had-hot-dinners-before-you-were-even-born-kid.

David’s about to embark on the sort of spiel I haven’t heard since Weeper The One-Ball Wonder took us young ’uns round the campfire and told us about his sexual exploits nearly 20 years ago…

“I had an older sister that had a lot of really nice girlfriends. So I used to walk to school with a lot of nice girls. I was like the young little… the young little brother they all needed to explore, so I had a lot of fun, actually, in my youth.” (cue mad laugh)

So you were used to it? It wasn’t really like winning the lottery when you became a pop star?

“Oh no. I learned pretty fast, I must say. I must boast.”

You were cut out for this life.

“You might say that (more mad laughter) it’s up to you. I didn’t say it.”

“I don’t want to get into that stuff, that’s, like, private, your private life. I like Nick Cave, the Stones a lot, my mate makes compilations of all kinds of stuff – Lynyrd Skynyrd. Stuff like that I really like, the Mid-West boogie, the old biker rockers.”

Do you ever go back to Basildon?

“Scary but, yes, I’ve been back a few times. In the last six years I’ve been back about three times. I get my mum to come to London. I’m like, ‘Mum, bring the flat round with you’. I just feel like I’m going to get arrested there or something. I walk out at the station and I’m like, ‘I want to go back, I want to go back’. I really do, it’s f---ing horrible.

“I walk past the taxi rank where I’ve been beaten up so many times or had a fight. The cab rank after the Mecca. F---ing hell, Basildon. It’s scary because you go back there and it’s exactly the same. It’s just a different generation. Very scary.”

How long can Depeche Mode continue?

“(Groans) I knew you were going to ask that question. I think it’s up to us, really. It’s up to all of us to feel we want to do it, of course.

“You know, there’s no way I’d make another record with the band or… I know it’s the same with Alan, everyone’s the same, unless they really felt it was worth it. Because we’re still, you know… everyone’s… I know we can make another great record. But you just really got to want to do it. I think after this tour if we, y’know…

“It’s a long way to go yet, we don’t finish until July or August next year. After that, everybody is going to want to take a lot of time off. To do some… just to go and y’know… aah.”

Have you ever been in a fist fight with anyone in the band?

“I actually haven’t, no. Fletch has had a fight with everyone but me. He’s never actually tried to hit me. But just lately I think he’s potentially been thinking about it.”

David doesn’t get the next question, my diction or my accent has him foxed.

“Where the f--- are you from?” he screams.

London, say I.

“But where is that accent from?”

Ireland, say I.

“But it’s mixed with London now. It’s just like Blade Runner, isn’t it?”

Eh?

“Soon there’s going to be another f---ing language everywhere. It’s getting hard to talk to people. What are they talking about?”

What do you like to do apart from music?

“I can’t wait to do the next thing, really. Aww, y’know, just… I’ve actually got lots and lots of friends now. I spend a lot of time with my friends. It’s something I’d forgot how to do, I think I sort of really isolated myself, not even intentionally but… over the years I had. Now I’ve made a lot of really, really good friends, good people. Mostly women, I may point out as well.”

That’s cool, it’s not illegal yet.

“Totally cool, especially when they’re all really good-looking as well.” (Cue hysterical schoolboy laughter of desperation)

It’s time to play that old game: I’ve-had-more-totty-than-you’ve-had-hot-dinners-before-you-were-even-born-kid.

David’s about to embark on the sort of spiel I haven’t heard since Weeper The One-Ball Wonder took us young ’uns round the campfire and told us about his sexual exploits nearly 20 years ago…

“I had an older sister that had a lot of really nice girlfriends. So I used to walk to school with a lot of nice girls. I was like the young little… the young little brother they all needed to explore, so I had a lot of fun, actually, in my youth.” (cue mad laugh)

So you were used to it? It wasn’t really like winning the lottery when you became a pop star?

“Oh no. I learned pretty fast, I must say. I must boast.”

You were cut out for this life.

“You might say that (more mad laughter) it’s up to you. I didn’t say it.”

The tap on the shoulder is about to come. So it’s time for a chatty query. Seen any good movies recently?

“We haven’t really had the chance. There’s in-house movies, stuff like that we have in the hotel, but I can never work out how to use the f---ing machine. I just play movies and forget about it, plug in the guitar and the ghetto-blaster, forget about it.”

The next day I’m in a taxi cab speeding towards central London with the Depeche Mode press officer. David Gahan is the cover star on a listings mag flagging the band’s show at Crystal Palace that weekend. The cover line reads: Crucifixion Or Resurrection: The Making Of A Rock God. [1] The press officer asks me what I think of the feature. The piece plays to the Depeche myth, David as a Rock God, ranting about the gig he’s just played being extra special, everything is hunky dory.

It feeds the fans what they want to hear, I guess it serves the magazine’s purposes, I tell them, though I feel that it’s not the real Depeche story, that it’s a con job.

“It serves its purpose for us, too,” decides the press officer.

Three days later, it’s early in the morning on August 1 at London’s Crystal Palace and The End Of The Depeche Mode European Tour Party is in full swing. After this they have a month off, then the campaign goes out to America. There’s vague talk that the tour may be 18 months long, but no one really believes it.

There’s a party within the party. In the middle of the floor, a leathery-faced security guy with shades and a walkie-talkie stands outside the door which provides the entry, up a spiral staircase, to the VIP free tequila and champagne bar. Only the band and their special guests are allowed in, so unlucky plebs like myself stand and wonder what’s going on up there.

Apparently what’s going on up there is LIVE SEX ACTS. Keen to protect their decadent image, Depeche have invited along performers – statuesque girls, suitably attired in conical bras, fishnet tights and no knickers. A bloke with a laminate describes the goings-on in the VIP bar as “very enjoyable”.

I think about the allegations made about ritual ‘abuse’ inside a certain heavy metal band and wonder if this sort of thing is really on. Is it decadence on a par with the Weimar Republic and the rotting Roman Empire?

But there’s more than one way of looking at it. Certainly Martin Gore’s songs have an ambivalent attitude to matters of flesh and spirituality, to sin and salvation. The Irish girl beside me says she spends a lot of time at clubs in Paris where men and women perform sex acts. Far from being disgusting, she says, it’s a very beautiful, very artistic thing.

So who are we mere mortals to judge, down here without a laminate, while the gods indulge themselves above us?

Beer in hand, Martin Gore takes his chances with the plebs but when he tries to walk through the crowd he is assailed at every turn.

The feverish Depeche grapevine has been wheeling and dealing once again.

“Everybody I bump into seems to be a fan. I don’t know how they all got in here,” he complains to the press officer. “Everybody I meet, it’s like, ‘Hey, do you remember me from Gothenburg?’”

David Gahan is nowhere to be seen. Someone tells me that they saw him last year in Spain during the recording of the band’s album and he looked “scary, painfully thin, like he was almost blue.”

Earlier, downstairs in his dressing room, David held court for his relatives, even his ex-wife and kid son were there. When a friend who hadn’t seen Gahan for some hears saw the singer he was shocked, “sad and angry” at the singer’s condition.

“Seeing him with his relatives was really weird,” he said, “seeing him with his son – there seemed to be an invisible wall between them.”

Gahan rushed across the room and grabbed his friend, clung to him with something close to desperation. He said they must get together, must talk. It seemed like he was anxious to make some link with the past but the next day Gahan would be back in the Mode machine, protected, cut off and his old friend wouldn’t be able to contact him.

As I’m about to leave, I bump into a Mode camp insider. What, I ask, are the chances of Gahan – whose speaking voice is still burned down to a husky whisper in between songs – making it through the tour?

“Who can say?” comes the reply. “We just have to wait and see what happens. David has to go through a lot of things, it’s something that no one, not even anyone else in the band can understand.

“No one can understand what it’s like to be a young man and you get all that money, all that fame. I’ve done everything I can to help. I think everybody has, it’s really up to David.

“This is something he must go through. It’s a hard job fronting a band like Depeche, but he must know that if it wasn’t for Martin there’d be no songs, if it wasn’t for Alan the records wouldn’t sound the way they do, and if it wasn’t for Fletch there probably wouldn’t be any money.

“I think it’s hard for David to accept that. I think he does a good job but he has a lot of problems. I think he’s looking for something really. I really think what he needs is love, he needs to be loved.”

Rock Gods, eh?

Maybe they’re just like everybody else after all.

“We haven’t really had the chance. There’s in-house movies, stuff like that we have in the hotel, but I can never work out how to use the f---ing machine. I just play movies and forget about it, plug in the guitar and the ghetto-blaster, forget about it.”

The next day I’m in a taxi cab speeding towards central London with the Depeche Mode press officer. David Gahan is the cover star on a listings mag flagging the band’s show at Crystal Palace that weekend. The cover line reads: Crucifixion Or Resurrection: The Making Of A Rock God. [1] The press officer asks me what I think of the feature. The piece plays to the Depeche myth, David as a Rock God, ranting about the gig he’s just played being extra special, everything is hunky dory.

It feeds the fans what they want to hear, I guess it serves the magazine’s purposes, I tell them, though I feel that it’s not the real Depeche story, that it’s a con job.

“It serves its purpose for us, too,” decides the press officer.

Three days later, it’s early in the morning on August 1 at London’s Crystal Palace and The End Of The Depeche Mode European Tour Party is in full swing. After this they have a month off, then the campaign goes out to America. There’s vague talk that the tour may be 18 months long, but no one really believes it.

There’s a party within the party. In the middle of the floor, a leathery-faced security guy with shades and a walkie-talkie stands outside the door which provides the entry, up a spiral staircase, to the VIP free tequila and champagne bar. Only the band and their special guests are allowed in, so unlucky plebs like myself stand and wonder what’s going on up there.

Apparently what’s going on up there is LIVE SEX ACTS. Keen to protect their decadent image, Depeche have invited along performers – statuesque girls, suitably attired in conical bras, fishnet tights and no knickers. A bloke with a laminate describes the goings-on in the VIP bar as “very enjoyable”.

I think about the allegations made about ritual ‘abuse’ inside a certain heavy metal band and wonder if this sort of thing is really on. Is it decadence on a par with the Weimar Republic and the rotting Roman Empire?

But there’s more than one way of looking at it. Certainly Martin Gore’s songs have an ambivalent attitude to matters of flesh and spirituality, to sin and salvation. The Irish girl beside me says she spends a lot of time at clubs in Paris where men and women perform sex acts. Far from being disgusting, she says, it’s a very beautiful, very artistic thing.

So who are we mere mortals to judge, down here without a laminate, while the gods indulge themselves above us?

Beer in hand, Martin Gore takes his chances with the plebs but when he tries to walk through the crowd he is assailed at every turn.

The feverish Depeche grapevine has been wheeling and dealing once again.

“Everybody I bump into seems to be a fan. I don’t know how they all got in here,” he complains to the press officer. “Everybody I meet, it’s like, ‘Hey, do you remember me from Gothenburg?’”

David Gahan is nowhere to be seen. Someone tells me that they saw him last year in Spain during the recording of the band’s album and he looked “scary, painfully thin, like he was almost blue.”

Earlier, downstairs in his dressing room, David held court for his relatives, even his ex-wife and kid son were there. When a friend who hadn’t seen Gahan for some hears saw the singer he was shocked, “sad and angry” at the singer’s condition.

“Seeing him with his relatives was really weird,” he said, “seeing him with his son – there seemed to be an invisible wall between them.”

Gahan rushed across the room and grabbed his friend, clung to him with something close to desperation. He said they must get together, must talk. It seemed like he was anxious to make some link with the past but the next day Gahan would be back in the Mode machine, protected, cut off and his old friend wouldn’t be able to contact him.

As I’m about to leave, I bump into a Mode camp insider. What, I ask, are the chances of Gahan – whose speaking voice is still burned down to a husky whisper in between songs – making it through the tour?

“Who can say?” comes the reply. “We just have to wait and see what happens. David has to go through a lot of things, it’s something that no one, not even anyone else in the band can understand.

“No one can understand what it’s like to be a young man and you get all that money, all that fame. I’ve done everything I can to help. I think everybody has, it’s really up to David.

“This is something he must go through. It’s a hard job fronting a band like Depeche, but he must know that if it wasn’t for Martin there’d be no songs, if it wasn’t for Alan the records wouldn’t sound the way they do, and if it wasn’t for Fletch there probably wouldn’t be any money.

“I think it’s hard for David to accept that. I think he does a good job but he has a lot of problems. I think he’s looking for something really. I really think what he needs is love, he needs to be loved.”

Rock Gods, eh?

Maybe they’re just like everybody else after all.

[1] - The magazine in question is Time Out, 28th July 1993.