- Joined

- Aug 15, 2019

- Messages

- 7,493

- Reaction score

- 143

- Points

- 63

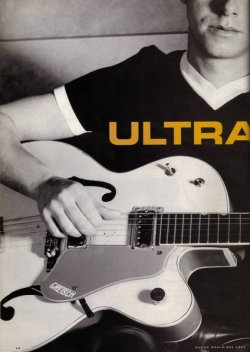

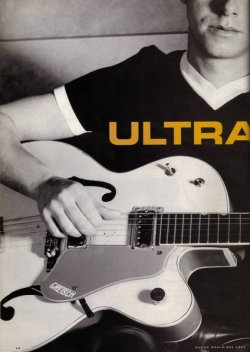

Ultra Sounds

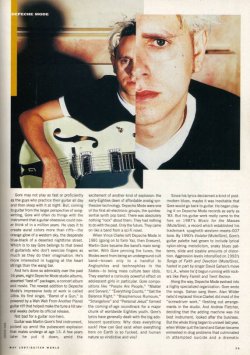

[Guitar World, May 1997. Words: Alan di Perna. Pictures: Alastair Thain.]

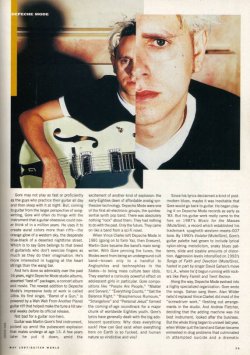

A close encounter with the ambient guitar world of Depeche Mode songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Martin Gore.

Seated in the rosy glow of his London hotel suite, Martin Gore plays a few tentative blues runs on a vintage Gretsch Anniversary that is as fine as the room’s antique furniture. “I don’t have any guitar heroes,” he confesses. “Those two words don’t really go together in my vocabulary.”

Gore himself probably isn’t anybody’s guitar hero. But that’s okay. He belongs to a completely different breed of guitarist. The guitar is hardly his sole claim to fame, or even his sole instrument. It’s just one of the tools he uses to bring life to the songs he writes for Depeche Mode.

Gore may not play as fast or proficiently as the guys who practice their guitar all day and then sleep with it at night. But, coming to guitar from the larger perspective of songwriting, Gore will often do things with the instrument that a guitar obsessive could never think of in a million years. He uses it to create aural colours more than riffs – the orange glow of a western sky, the desperate blue-black of a deserted nighttime street. Which is to say Gore belongs to that breed of guitarists who don’t exercise fingers as much as they do their imagination. He’s more interested in tugging at the heart strings than the wang bar.

And he’s done so admirably over the past 16 years, eight Depeche Mode studio albums, assorted ‘best of’ packages, a concert album and movie. The newest addition to Depeche Mode’s impressive body of work is called Ultra. Its first single, “Barrel of a Gun”, is powered by a Wah Wah From Another Planet guitar riff that helped make the tune a hit several weeks before its official release.

Not bad for a guitar non-hero.

Guitar was Martin Gore’s first instrument, picked up amid the pubescent explosion that males undergo at age 13. A few years later he put it down, amid the excitement of another kind of explosion: the early-Eighties dawn of affordable analog synthesizer technology. Depeche Mode were one of the first all-electronic groups, the quintessential synth pop band. There was absolutely nothing ‘rock’ about them. They had nothing to do with the past. Only the future. They came on like a band from a sci-fi novel.

When Vince Clarke left Depeche Mode in 1981 (going on to form Yaz, then Erasure), Martin Gore became the band’s main songwriter. With Gore penning the tunes, the Modes went from being an underground cult band – known only to a handful of Anglophiles and technophiles in the States – to being mass culture teen idols. They exerted a curiously powerful effect on adolescent girls in particular. Gore compositions like ‘People Are People’, ‘Master And Servant’, ‘Everything Counts’, ‘Get The Balance Right’, ‘Blasphemous Rumours’, ‘Strangelove’ and ‘Personal Jesus’ formed the coming-of-age soundtrack to a major chunk of worldwide Eighties youth. Gore’s lyrics have generally dealt with the big adolescent questions: Why does everything suck? How can God exist when everything here on Earth is so fucked, and human nature so vindictive and vile?

Since his lyrics declaimed a kind of post-modern blues, maybe it was inevitable that Gore would go back to guitar. He began playing it on Depeche Mode records as early as ’83. But his guitar work really came to the fore on 1987’s Music For The Masses (Mute / Sire), a record which established his trademark spaghetti-western-meets-007 tone. By 1990’s Violator (Mute / Sire), Gore’s guitar palette had grown to include lyrical nylon-string melodicism, snaky blues patterns, slide and sizeable amounts of distortion. Aggression levels intensified on 1993’s Songs of Faith and Devotion (Mute / Sire), fuelled in part by singer David Gahan’s move to L.A., where he’d begun running with rockers like Perry Farrell and Trent Reznor.

Along the way, Depeche Mode evolved into a highly specialized organization. Gore wrote the songs. Gahan sang them. Alan Wilder (who’d replaced Vince Clarke) did most of the ‘screwdriver work’, fleshing out arrangements in the studio. And Andrew Fletcher, deciding that the adding machine was his best instrument, looked after the business. But the whole thing began to unravel last year, when Wilder quit the band and Gahan became enmeshed in drug problems that culminated in attempted suicide and a dramatic Memorial Day arrest.

It might have been the end of the line for Depeche Mode. But instead, Gore soldiered on, writing new songs end entering the studio with producer Tim Simenon (celebrated for the ground-breaking electronic dance records he’d recorded under the name Bomb the Bass, and for his production work with Bjork, Neneh Cherry, Sinead O’Connor and Seal.)

Meanwhile, Fletcher continued looking after the finances. Gahan underwent rehab and began working with a vocal coach to regain the voice that had fallen into disuse during his period of drug excess. In time, he was in good enough shape to join in on the sessions with the band in London and New York.

The result is the aforementioned Ultra. It’s the biggest stylistic leap Depeche Mode has taken in a long time, drawing on the limpid blue cool of modern electronic dance styles like ambient, trip hop, jungle and drum & bass. Though the big single, “Barrel of a Gun”, burns with strident urgency, most of the other cuts have a kind of stark, still beauty that quietly eludes stylistic categorization.

“There are a lot of different influences there,” says Gore. “There are all these very small parts that go into a big mixing pot that somehow comes out sounding like Depeche Mode. Probably because of the way I write and the way Dave sings. Those are the constants.”

[Guitar World, May 1997. Words: Alan di Perna. Pictures: Alastair Thain.]

A remarkable, detailed interview with Martin for a guitar magazine. The interviewer focuses on the band's use of guitars but with never loses sight of the fact that Depeche Mode are not primarily a guitar band. Priceless for a guitar enthusiast and currently the only article I have of its kind.

" Gore belongs to that breed of guitarists who don’t exercise fingers as much as they do their imagination. He’s more interested in tugging at the heart strings than the wang bar. "

A close encounter with the ambient guitar world of Depeche Mode songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Martin Gore.

Seated in the rosy glow of his London hotel suite, Martin Gore plays a few tentative blues runs on a vintage Gretsch Anniversary that is as fine as the room’s antique furniture. “I don’t have any guitar heroes,” he confesses. “Those two words don’t really go together in my vocabulary.”

Gore himself probably isn’t anybody’s guitar hero. But that’s okay. He belongs to a completely different breed of guitarist. The guitar is hardly his sole claim to fame, or even his sole instrument. It’s just one of the tools he uses to bring life to the songs he writes for Depeche Mode.

Gore may not play as fast or proficiently as the guys who practice their guitar all day and then sleep with it at night. But, coming to guitar from the larger perspective of songwriting, Gore will often do things with the instrument that a guitar obsessive could never think of in a million years. He uses it to create aural colours more than riffs – the orange glow of a western sky, the desperate blue-black of a deserted nighttime street. Which is to say Gore belongs to that breed of guitarists who don’t exercise fingers as much as they do their imagination. He’s more interested in tugging at the heart strings than the wang bar.

And he’s done so admirably over the past 16 years, eight Depeche Mode studio albums, assorted ‘best of’ packages, a concert album and movie. The newest addition to Depeche Mode’s impressive body of work is called Ultra. Its first single, “Barrel of a Gun”, is powered by a Wah Wah From Another Planet guitar riff that helped make the tune a hit several weeks before its official release.

Not bad for a guitar non-hero.

Guitar was Martin Gore’s first instrument, picked up amid the pubescent explosion that males undergo at age 13. A few years later he put it down, amid the excitement of another kind of explosion: the early-Eighties dawn of affordable analog synthesizer technology. Depeche Mode were one of the first all-electronic groups, the quintessential synth pop band. There was absolutely nothing ‘rock’ about them. They had nothing to do with the past. Only the future. They came on like a band from a sci-fi novel.

When Vince Clarke left Depeche Mode in 1981 (going on to form Yaz, then Erasure), Martin Gore became the band’s main songwriter. With Gore penning the tunes, the Modes went from being an underground cult band – known only to a handful of Anglophiles and technophiles in the States – to being mass culture teen idols. They exerted a curiously powerful effect on adolescent girls in particular. Gore compositions like ‘People Are People’, ‘Master And Servant’, ‘Everything Counts’, ‘Get The Balance Right’, ‘Blasphemous Rumours’, ‘Strangelove’ and ‘Personal Jesus’ formed the coming-of-age soundtrack to a major chunk of worldwide Eighties youth. Gore’s lyrics have generally dealt with the big adolescent questions: Why does everything suck? How can God exist when everything here on Earth is so fucked, and human nature so vindictive and vile?

Since his lyrics declaimed a kind of post-modern blues, maybe it was inevitable that Gore would go back to guitar. He began playing it on Depeche Mode records as early as ’83. But his guitar work really came to the fore on 1987’s Music For The Masses (Mute / Sire), a record which established his trademark spaghetti-western-meets-007 tone. By 1990’s Violator (Mute / Sire), Gore’s guitar palette had grown to include lyrical nylon-string melodicism, snaky blues patterns, slide and sizeable amounts of distortion. Aggression levels intensified on 1993’s Songs of Faith and Devotion (Mute / Sire), fuelled in part by singer David Gahan’s move to L.A., where he’d begun running with rockers like Perry Farrell and Trent Reznor.

Along the way, Depeche Mode evolved into a highly specialized organization. Gore wrote the songs. Gahan sang them. Alan Wilder (who’d replaced Vince Clarke) did most of the ‘screwdriver work’, fleshing out arrangements in the studio. And Andrew Fletcher, deciding that the adding machine was his best instrument, looked after the business. But the whole thing began to unravel last year, when Wilder quit the band and Gahan became enmeshed in drug problems that culminated in attempted suicide and a dramatic Memorial Day arrest.

It might have been the end of the line for Depeche Mode. But instead, Gore soldiered on, writing new songs end entering the studio with producer Tim Simenon (celebrated for the ground-breaking electronic dance records he’d recorded under the name Bomb the Bass, and for his production work with Bjork, Neneh Cherry, Sinead O’Connor and Seal.)

Meanwhile, Fletcher continued looking after the finances. Gahan underwent rehab and began working with a vocal coach to regain the voice that had fallen into disuse during his period of drug excess. In time, he was in good enough shape to join in on the sessions with the band in London and New York.

The result is the aforementioned Ultra. It’s the biggest stylistic leap Depeche Mode has taken in a long time, drawing on the limpid blue cool of modern electronic dance styles like ambient, trip hop, jungle and drum & bass. Though the big single, “Barrel of a Gun”, burns with strident urgency, most of the other cuts have a kind of stark, still beauty that quietly eludes stylistic categorization.

“There are a lot of different influences there,” says Gore. “There are all these very small parts that go into a big mixing pot that somehow comes out sounding like Depeche Mode. Probably because of the way I write and the way Dave sings. Those are the constants.”