You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

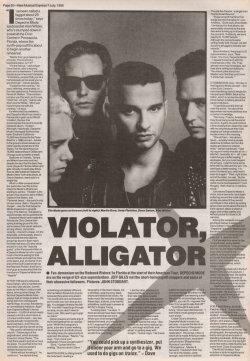

Depeche Mode Violator, Alligator (NME, 1990)

" Bruce Kirkland, the group’s U.S. representative, says, “New Order, the Cure, Depeche Mode – I equate these bands with the metal bands of the Seventies. They almost never had hit singles, but they were selling out stadiums. The classic joke about Iron Maiden was that they sold more T-shirts than records.” "

Reprint of a Rolling Stone article before the kick-off of the World Violation Tour in Florida. As this is their first appearance since the band really made a name for themselves in the USA, the article takes them to be very much an unknown quantity, examining their misconceptions and cult appeal, and the fact that even the fans don't know their names...

Depeche Mode may sell millions of albums and play to capacity crowds in huge football stadiums, but these technopop idols still aren’t happy.

“I’ve been called a faggot about twenty times today,” says Depeche Mode keyboardist Alan Wilder, who’s slumped down in a seat at the Civic Center in Pensacola, Florida, where the British synth-pop outfit is about to begin another rehearsal. “Mostly from guys leaning out of trucks. This is a sort of backward place, isn’t it?”

“It’s the haircut,” says singer Dave Gahan, who’s wearing jeans and a sleeveless T-shirt that depicts a pair of women’s breasts. “In America, people think you’re homosexual just because you’ve got short hair.” Gahan pauses. “Except for the marines,” he says, referring, presumably, to the men stationed at Pensacola’s Naval Air Station. “The marines just give you this wink, as if to say, ‘Short hair. All right.’” Gahan sits down next to Wilder. “We’ll just have to hang out with the marines,” he says.

It’s Memorial Day weekend, and Depeche Mode has come to Pensacola to gear up for World Violation, the tour that accompanies the band’s recently released album, Violator. Although, historically, Depeche Mode’s strongest foothold has been Southern California – 75,000 fans flocked to the Rose Bowl for a 1988 concert – tickets to the group’s shows always go rather quickly everywhere. For the upcoming tour, 18,000-seat arenas in Dallas and Chicago sold out within a week. Stadiums in Orlando, Tampa and Miami have also sold out, despite the fact that the band has never played Florida before and gets virtually no radio airplay there. And 42,000 tickets to Depeche Mode’s New York-area show, at Giants Stadium, were sold in a single day.

What’s a little unusual about this particular road trip is that Depeche Mode’s albums are starting to sell as well. Violator is the group’s first record to sell a million copies in the States, and “Personal Jesus” – the band’s only hit here since 1985’s “People Are People” – was the first Depeche Mode single ever to go gold. “Enjoy The Silence”, the album’s second single, will be gold shortly.

Depeche Mode has made the Pensacola Civic Center its spring training ground for the same reason that Janet Jackson, among others, came here recently: The rent’s cheap. On the downside, unfortunately, there’s the fact that the only club the group has found in town has a mirrored ball and a DJ who struts around in a tux; the fact that the “security guard” at the Pensacola Hilton is a Depeche Mode fan who’s spent most of his time asking for free concert tickets and eight-by-tens of the band; and, of course, the fact that in an area of the Gulf Coast known as the Redneck Riviera, there are a lot of guys in trucks who think the members of Depeche Mode are “faggots”.

After the band’s rehearsal, Dave Gahan, who’s married and has a two-year-old son, comes down to the Hilton’s lobby to talk about, among other things, the fact that Depeche Mode has always had an image problem. [1] He brings with him a bodyguard named Ingo. In a way, this seems an unnecessary measure. Apart from Depeche Mode’s devout followers – 15,000 of whom nearly caused a riot at a Wherehouse record store in L.A. a few months back [2] – very few people actually recognize the band members. And if they do, they tend to get the names wrong.

These days, Depeche Mode – which, in addition to Gahan and Wilder, includes keyboardist Andy Fletcher and songwriter Martin Gore – gives relatively few interviews. The band has been known to turn away journalists who haven’t pledged allegiance, as well as to boycott radio stations that balk at the group’s all-synthesizer format and decline to play its records.

“There was this band that everybody loved to hate,” Gahan says of Depeche Mode. “And yet they were incredibly successful. Why? Why do you think you’re so successful? Why do you think you’re on this planet, basically? It got to the point in interviews where we’d just say, ‘Fuck you,’ and walk out.” [3]

After this brief speech, which may or may not be a warning, Gahan begins talking freely about Depeche Mode’s ancient history. He even asks, then answers, what Martin Gore considers to be the most tired Depeche Mode-related questions: “Where’s your drummer Where are your guitars Do you consider this real music?”

“We used to rehearse in a local church,” Gahan says of the original band, which formed outside London, in working-class Basildon, in 1980, and which included Erasure’s Vince Clarke. “The vicar there used to just let us have the place. You had to be nice and polite, and you weren’t allowed to play too loud.

“I think without knowing it,” he continues, “we started doing something completely different. We had taken these instruments because they were convenient. You could pick up a synthesizer, put it under your arm and go to a gig. You plugged directly into the PA. You didn’t need to go through an amp, so you didn’t need to have a van. We used to go to gigs on trains.”

The band, which had been getting steady work at a couple of nearby pubs, eventually made a demo tape. Instead of mailing cassettes to the various labels, Clarke and Gahan delivered the original quarter-inch tape personally. “Vince and I used to go ’round to record companies and demand that they play it,” Gahan says, laughing. “Most of them, of course, would tell us to fuck off. They’d say, ‘Leave the tape with us,’ and we’d say, ‘No, it’s our only one.’ Then we’d say goodbye and go off somewhere else.”

Gahan pauses and asks Ingo if he’d mind getting him an orange juice. While the bodyguard’s gone, a fan who’s been walking nervously back and forth across the lobby takes the opportunity to approach the singer. “Martin,” he says. “Can I have your autograph? Have you got a pen?”

“Sure,” Gahan tells him, smiling. “But my name’s Dave.”

Last edited:

A few moments later, Gahan, orange juice in hand, is trying to pinpoint what it was that first made Depeche Mode attractive to the record companies. “At the time,” he says, “everybody was using electronics in a very morbid, gloomy way. Suddenly, here was this pop band that was using the stuff – these young kids who had everybody dancing, instead of standing around in gray raincoats about to commit suicide.”

After considering offers from major labels like Phonogram – “money you could never have imagined and all sorts of crazy things, like clothes allowances” – Depeche Mode signed on with Daniel Miller at the independent label Mute. (The band, which is signed to Sire Records in the U.S., has never had a manager.) In 1981, the group released its debut album, Speak and Spell, which, with some help from the dance-floor hit “Just Can’t Get Enough”, made the Top Ten in England. Shortly thereafter, Vince Clarke – then Depeche Mode’s driving force and chief songwriter – left the band to form Yazoo and, later, Erasure. Clarke claimed he was sick of touring.

“That’s what he said, but I think that’s a lot of bullshit, to be quite honest,” Gahan says. “I think he’d just taken it as far as he could. We were very successful. We were in every pop magazine. We were on the TV shows. Everything was going right for Depeche Mode. Everybody wanted to know about Depeche Mode. I think Vince suddenly lost interest in it – and he started getting letters from fans asking what kind of socks he wore.

“Martin had written a couple of songs,” Gahan continues, “and we went into the studio and recorded ‘See You’, which was our biggest hit so far. So that was it. ’Bye, Vince.” [4]

Martin Gore is sitting beside the hotel pool, reading a biography of Herman Hesse. He is shirtless, wearing long, black shorts and white knee socks. He looks much like he looks onstage these days: a blond, curly-haired answer to AC/DC’s Angus Young. “Looking back,” he is saying, “I think we should have been slightly more worried than we were. When your chief songwriter leaves the band, you should worry a bit. I suppose that’s one of the good things about being young. If we had panicked, we probably wouldn’t be here today.”

Like the other members of Depeche Mode, who are all in their late twenties, Gore is quite personable – funny, soft-spoken and without any real pretensions. Unlike the other members of the band, he plays some guitar during the live performances, has released a solo album of cover songs and, a few years back, used to go onstage in a skirt. “Martin said to me once, ‘I like to look into the mirror before I go out, and laugh and think, ‘Look what I’m getting away with tonight’,” Gahan says. “He’d wear leather trousers and then wear a skirt over the top. And then he sort of extended to just wearing a skirt. We used to sit backstage saying, ‘Martin, you can’t fucking wear that, man! You’ve got to take that off!’”

“I just thought it was quite funny,” Gore says dismissively. “I didn’t think it was going to cause such a fuss.”

Under Gore’s direction, Depeche Mode’s music became – to quote the title of an album that many of the group’s fans hold dearest – a “black celebration”. His songs, a few of which have made American radio programmers blush, have been both profane (“Blasphemous Rumours”) and kinky (“Strangelove”, “Master & Servant”). The band’s first Top Ten hit in the States, oddly enough, was the kind-spirited “People Are People”, a single from Some Great Reward.

“It was around that time that things started changing for us in America”, Gore says, at poolside. “On the tour for that album, we were totally shocked by the way fans were turning up in droves at the concerts. Suddenly, we were playing to 10,000 people. Although the concerts were selling really well, though, we still found it a struggle to actually sell records.”

Bruce Kirkland, the group’s U.S. representative, says, “New Order, the Cure, Depeche Mode – I equate these bands with the metal bands of the Seventies. They almost never had hit singles, but they were selling out stadiums. The classic joke about Iron Maiden was that they sold more T-shirts than records.”

It’s Memorial Day – the day of the Depeche Mode concert – and at the Civic Center’s merchandising stand a single fan has just spent $686. Back at the Hilton, which is across the street, Dave Gahan is talking about the band’s followers. “I’d get kids coming from all over the world,” he says of the days when his home address was common knowledge. “Germany, France, America – they’d just hang out at the end of my drive. It got to the point where I’d be chasing them down the road with my dog because they’d be singing our songs outside my house at two in the morning.”

“One of them – his name’s Sean – actually hired a private detective to follow me from the studio and discover where I lived,” Gahan continues. “I lost my rag and really shouted at him. I told him, basically to fuck off. Later I sent the guy a letter saying, ‘I apologize, but you must respect my privacy. I want to have some time with my wife and son.’ He sent back a letter saying, ‘I’m sorry I bothered you, and I won’t ever do it again.’ Then, right at the end of the letter, he said, ‘By the way, would it be possible for me to come ’round next weekend?’ I just thought, ‘Well, that’s it. It’s time to move.’”

Just before Depeche Mode’s show, some fans who have been puttering around the hotel lobby all day are asked if they would contribute to this article by writing down a few words about the band. Each agrees, takes a sheet of paper and writes quietly and without pause for close to thirty minutes. Among the subjects covered are Dave Gahan’s sideburns; Dave Gahan’s hips; the fact that “Depeche” puts on a “spectacular” live show; the fact that the band members aren’t pompous rock stars but “v. down to earth”.

One teenage boy says he has “every B side, every weirdo import, everything”. One girl says she has “loved Depeche Mode since they first came out” – unlikely, unless she was hooked on Speak and Spell at the age of seven – and returns a fairly representative essay, which reads in part: “Tonight I jumped out in front of Martin Gore and got a picture. I swear I almost fainted. He seems so complex. I would love to sit down and just discuss with Martin Gore what I interpret in his music… I feel that once I meet Martin Gore there is nothing I can’t accomplish. His touch will burn, throw me and feel me up with energy. (Razal, 16, Fort Walton Beach, Florida)”

For a band that is, as Andy Fletcher puts it, “supposed to be cold and robotic and love studios”, Depeche Mode puts on a good, old-fashioned arena show. Gahan, who wears a black studded-leather jacket and matching pants, has a pretty complete repertoire of moves: the jumping jack, the spinning top, the bump-and-grind and a sort of standing duckwalk. Several songs are accompanied by photographer Anton Corbijn’s videos, including a hilarious segment in which Martin Gore dresses as a character Corbijn refers to as “the bondage angel”. All the songs benefit from an over-the-top light show that looks a little like the last scene from Close Encounters.

The World Violation Tour includes a fairly straightforward selection of Depeche Mode songs: “Shake the Disease”, “Never Let Me Down Again”, “Stripped” and “Everything Counts”, which was a U.K hit in 1983 and was reissued last year to coincide with D.A. Pennebaker’s Depeche Mode film documentary, 101. Martin Gore, who is quite short and who is usually seen only as a shock of blond hair peeking up over a stack of keyboards, comes front and center at one point in the show to sing two solo acoustic-guitar numbers: “I Want You Now” and “Word Full of Nothing”. The band’s final encore is a guitar-driven cover of “Route 66”.

Needless to say, the crowd at the Pensacola Civic Center is in a state of pandemonium for most of the two hours that “Depeche” is onstage. Many of the songs that go over best, however, are from Violator: “Clean”, “Personal Jesus” and “Policy of Truth”, the album’s third single, which begins with a vaguely funky “Heard It Through the Grapevine”-style sequence.

In general, Violator seems to have permanently opened doors for the band in America. “Martin once said, ‘Perhaps if we called ourselves a rock band from day 1, we would have had a lot more credibility from day 1,’” says Gahan after the show. “But we’ve stuck to calling ourselves a pop band, and we’ve earned that credibility by gaining success until people couldn’t ignore us anymore.”

After considering offers from major labels like Phonogram – “money you could never have imagined and all sorts of crazy things, like clothes allowances” – Depeche Mode signed on with Daniel Miller at the independent label Mute. (The band, which is signed to Sire Records in the U.S., has never had a manager.) In 1981, the group released its debut album, Speak and Spell, which, with some help from the dance-floor hit “Just Can’t Get Enough”, made the Top Ten in England. Shortly thereafter, Vince Clarke – then Depeche Mode’s driving force and chief songwriter – left the band to form Yazoo and, later, Erasure. Clarke claimed he was sick of touring.

“That’s what he said, but I think that’s a lot of bullshit, to be quite honest,” Gahan says. “I think he’d just taken it as far as he could. We were very successful. We were in every pop magazine. We were on the TV shows. Everything was going right for Depeche Mode. Everybody wanted to know about Depeche Mode. I think Vince suddenly lost interest in it – and he started getting letters from fans asking what kind of socks he wore.

“Martin had written a couple of songs,” Gahan continues, “and we went into the studio and recorded ‘See You’, which was our biggest hit so far. So that was it. ’Bye, Vince.” [4]

Martin Gore is sitting beside the hotel pool, reading a biography of Herman Hesse. He is shirtless, wearing long, black shorts and white knee socks. He looks much like he looks onstage these days: a blond, curly-haired answer to AC/DC’s Angus Young. “Looking back,” he is saying, “I think we should have been slightly more worried than we were. When your chief songwriter leaves the band, you should worry a bit. I suppose that’s one of the good things about being young. If we had panicked, we probably wouldn’t be here today.”

Like the other members of Depeche Mode, who are all in their late twenties, Gore is quite personable – funny, soft-spoken and without any real pretensions. Unlike the other members of the band, he plays some guitar during the live performances, has released a solo album of cover songs and, a few years back, used to go onstage in a skirt. “Martin said to me once, ‘I like to look into the mirror before I go out, and laugh and think, ‘Look what I’m getting away with tonight’,” Gahan says. “He’d wear leather trousers and then wear a skirt over the top. And then he sort of extended to just wearing a skirt. We used to sit backstage saying, ‘Martin, you can’t fucking wear that, man! You’ve got to take that off!’”

“I just thought it was quite funny,” Gore says dismissively. “I didn’t think it was going to cause such a fuss.”

Under Gore’s direction, Depeche Mode’s music became – to quote the title of an album that many of the group’s fans hold dearest – a “black celebration”. His songs, a few of which have made American radio programmers blush, have been both profane (“Blasphemous Rumours”) and kinky (“Strangelove”, “Master & Servant”). The band’s first Top Ten hit in the States, oddly enough, was the kind-spirited “People Are People”, a single from Some Great Reward.

“It was around that time that things started changing for us in America”, Gore says, at poolside. “On the tour for that album, we were totally shocked by the way fans were turning up in droves at the concerts. Suddenly, we were playing to 10,000 people. Although the concerts were selling really well, though, we still found it a struggle to actually sell records.”

Bruce Kirkland, the group’s U.S. representative, says, “New Order, the Cure, Depeche Mode – I equate these bands with the metal bands of the Seventies. They almost never had hit singles, but they were selling out stadiums. The classic joke about Iron Maiden was that they sold more T-shirts than records.”

It’s Memorial Day – the day of the Depeche Mode concert – and at the Civic Center’s merchandising stand a single fan has just spent $686. Back at the Hilton, which is across the street, Dave Gahan is talking about the band’s followers. “I’d get kids coming from all over the world,” he says of the days when his home address was common knowledge. “Germany, France, America – they’d just hang out at the end of my drive. It got to the point where I’d be chasing them down the road with my dog because they’d be singing our songs outside my house at two in the morning.”

“One of them – his name’s Sean – actually hired a private detective to follow me from the studio and discover where I lived,” Gahan continues. “I lost my rag and really shouted at him. I told him, basically to fuck off. Later I sent the guy a letter saying, ‘I apologize, but you must respect my privacy. I want to have some time with my wife and son.’ He sent back a letter saying, ‘I’m sorry I bothered you, and I won’t ever do it again.’ Then, right at the end of the letter, he said, ‘By the way, would it be possible for me to come ’round next weekend?’ I just thought, ‘Well, that’s it. It’s time to move.’”

Just before Depeche Mode’s show, some fans who have been puttering around the hotel lobby all day are asked if they would contribute to this article by writing down a few words about the band. Each agrees, takes a sheet of paper and writes quietly and without pause for close to thirty minutes. Among the subjects covered are Dave Gahan’s sideburns; Dave Gahan’s hips; the fact that “Depeche” puts on a “spectacular” live show; the fact that the band members aren’t pompous rock stars but “v. down to earth”.

One teenage boy says he has “every B side, every weirdo import, everything”. One girl says she has “loved Depeche Mode since they first came out” – unlikely, unless she was hooked on Speak and Spell at the age of seven – and returns a fairly representative essay, which reads in part: “Tonight I jumped out in front of Martin Gore and got a picture. I swear I almost fainted. He seems so complex. I would love to sit down and just discuss with Martin Gore what I interpret in his music… I feel that once I meet Martin Gore there is nothing I can’t accomplish. His touch will burn, throw me and feel me up with energy. (Razal, 16, Fort Walton Beach, Florida)”

For a band that is, as Andy Fletcher puts it, “supposed to be cold and robotic and love studios”, Depeche Mode puts on a good, old-fashioned arena show. Gahan, who wears a black studded-leather jacket and matching pants, has a pretty complete repertoire of moves: the jumping jack, the spinning top, the bump-and-grind and a sort of standing duckwalk. Several songs are accompanied by photographer Anton Corbijn’s videos, including a hilarious segment in which Martin Gore dresses as a character Corbijn refers to as “the bondage angel”. All the songs benefit from an over-the-top light show that looks a little like the last scene from Close Encounters.

The World Violation Tour includes a fairly straightforward selection of Depeche Mode songs: “Shake the Disease”, “Never Let Me Down Again”, “Stripped” and “Everything Counts”, which was a U.K hit in 1983 and was reissued last year to coincide with D.A. Pennebaker’s Depeche Mode film documentary, 101. Martin Gore, who is quite short and who is usually seen only as a shock of blond hair peeking up over a stack of keyboards, comes front and center at one point in the show to sing two solo acoustic-guitar numbers: “I Want You Now” and “Word Full of Nothing”. The band’s final encore is a guitar-driven cover of “Route 66”.

Needless to say, the crowd at the Pensacola Civic Center is in a state of pandemonium for most of the two hours that “Depeche” is onstage. Many of the songs that go over best, however, are from Violator: “Clean”, “Personal Jesus” and “Policy of Truth”, the album’s third single, which begins with a vaguely funky “Heard It Through the Grapevine”-style sequence.

In general, Violator seems to have permanently opened doors for the band in America. “Martin once said, ‘Perhaps if we called ourselves a rock band from day 1, we would have had a lot more credibility from day 1,’” says Gahan after the show. “But we’ve stuck to calling ourselves a pop band, and we’ve earned that credibility by gaining success until people couldn’t ignore us anymore.”

[1] - By 1990 this subject was not only getting tired but fast becoming outdated. I can't tell whether, by bringing it up again and refusing to let it get forgotten, they were developing chips on their shoulders, or whether they were far more savvy than they let on to the idea of cult popularity and were using the matter to stick two fingers up at the music industry.

[2] - Read about that here.

[3] - In this interview in the USA a couple of years previously, Andy put down an interviewer spectacularly for taking this kind of approach:

- "Even though a radio programmer's ear might not hear it, why are all these people following you from venue to venue in droves?"

- "Because it's really good music, that's why."

[4] - Try this article for a better picture from nearer the time of what was happening in the band.

Last edited:

Bruce Kirkland calls the band’s recent boom “a classic U2 scenario”, referring to the fact that, with The Joshua Tree, U2’s record sales finally reflected the group’s considerable live following. “It’s Depeche Mode’s time,” Kirkland says, “and the industry is finally catching up.” Most important, no doubt, is the fact that Depeche Mode songs have at last found a home on Top Forty radio.

“Here in the States, we’ve been working on it for years and years,” Gore says. “I think in a way we’ve been at the forefront of new music, sort of chipping away at the standard rock-format radio stations. And I think with this record, we’ve finally managed to bulldoze our way through.”

It’s been a pleasant turn of events for Depeche Mode, because there is still no place lonelier, or more vast, than the synth-pop graveyard. “It was the Human League, in particular, who went full circle,” Gore says. “They had a note on their album that I thought was just ridiculous. You know, ‘No sequencers used on this record.’ A lot of people get swayed by the ‘real’ music thing. They think you can’t make soul music by using computers and synthesizers and samplers, which we think is totally wrong. We think the soul in the music comes from the song. The instrumentation doesn’t matter at all.”

“The beauty of using electronics is that music can now be made in your bedroom”, Andy Fletcher adds. “You don’t need to get four people together in some warehouse to practice. You don’t have to have four excellent musicians fighting amongst themselves. You can do it in your bedroom, and it’s all down to ideas.” Fletcher pauses. “Obviously, it’s sad to see the demise of the traditional rock group,” he says. “But there’s always going to be a place for it in cabaret.”

It’s one o’clock in the morning, and Razal – the young essayist who said she could accomplish anything if she could just meet Martin Gore – has been introduced to her idol. The pair have been talking quietly in the hotel bar for two hours.

Out in the lobby, a fan who’s been hanging around for days is crying. He offered the band a photograph – a picture of himself and his girlfriend, which had been taken at their high-school prom – and the band didn’t seem to want it. Dave Gahan goes out to talk to him, finds the situation hopeless and heads up to his room.

Before Gahan can get to the elevator, however, someone – obviously not a true Depeche fan – jumps in front of him and says, “Martin, can I have your autograph?”

Gahan rolls his eyes, momentarily fed up with living the strange life of an anonymous pop star. “To begin with, my name’s Dave,” he says, “and I don’t have a pen.”

It's A Fan's Fan's World

Thanks to D.A. Pennebaker’s Documentary film Depeche Mode 101, even the band’s fans have fans.

It seems safe to say that Depeche Mode had U2’s Live at Red Rocks in mind when the band approached Pennebaker (who also made Monterey Pop and Bob Dylan’s Don’t Look Back) to make 101. The film was meant to cash in on the group’s strongest selling point – its live performances – but it also sought to capture the spirit of Depeche Mode’s following. It might not have been until after the film was made, however, that the band began to realize just how devout that following was.

The documentary – released last year, along with a double live album bearing the same name – features a busload of teenage contest winners who follow the group on the last leg of its Music For The Masses Tour. The fans dance around in the bus, fix their hair, make pit stops for beer and have conversations like this: “Where are we going today?” “Graceland, probably.” “What’s Graceland?”

Margaret Mouzakitis was one of the contest winners, and she now works for the firm that represents Depeche Mode in the U.S.. She gets only a few minutes’ worth of screen time during 101 – which, along with Anton Corbijn’s long-form video Strange – has become required viewing for all serious students of Depeche Mode. Still, when Mouzakitis travels with the group, she is regularly approached by awestruck fans who ask her, “Weren’t you on the bus?”

Theresa Conroy – a young press liaison who appears several times during the film – gets the same sort of double takes. And because she introduces herself to someone at one point in the documentary, Conroy often finds that Depeche Mode fans know her name. One such fan even tried to use it. During the recording of Violator, singer Dave Gahan got a phone call from someone claiming to be Theresa Conroy. After a few moments, Gahan laughed and said, “You’re not TC!” He banged the receiver on the table to get the impostor’s attention, then told her, “You’ve been a very naughty girl."

“Here in the States, we’ve been working on it for years and years,” Gore says. “I think in a way we’ve been at the forefront of new music, sort of chipping away at the standard rock-format radio stations. And I think with this record, we’ve finally managed to bulldoze our way through.”

It’s been a pleasant turn of events for Depeche Mode, because there is still no place lonelier, or more vast, than the synth-pop graveyard. “It was the Human League, in particular, who went full circle,” Gore says. “They had a note on their album that I thought was just ridiculous. You know, ‘No sequencers used on this record.’ A lot of people get swayed by the ‘real’ music thing. They think you can’t make soul music by using computers and synthesizers and samplers, which we think is totally wrong. We think the soul in the music comes from the song. The instrumentation doesn’t matter at all.”

“The beauty of using electronics is that music can now be made in your bedroom”, Andy Fletcher adds. “You don’t need to get four people together in some warehouse to practice. You don’t have to have four excellent musicians fighting amongst themselves. You can do it in your bedroom, and it’s all down to ideas.” Fletcher pauses. “Obviously, it’s sad to see the demise of the traditional rock group,” he says. “But there’s always going to be a place for it in cabaret.”

It’s one o’clock in the morning, and Razal – the young essayist who said she could accomplish anything if she could just meet Martin Gore – has been introduced to her idol. The pair have been talking quietly in the hotel bar for two hours.

Out in the lobby, a fan who’s been hanging around for days is crying. He offered the band a photograph – a picture of himself and his girlfriend, which had been taken at their high-school prom – and the band didn’t seem to want it. Dave Gahan goes out to talk to him, finds the situation hopeless and heads up to his room.

Before Gahan can get to the elevator, however, someone – obviously not a true Depeche fan – jumps in front of him and says, “Martin, can I have your autograph?”

Gahan rolls his eyes, momentarily fed up with living the strange life of an anonymous pop star. “To begin with, my name’s Dave,” he says, “and I don’t have a pen.”

It's A Fan's Fan's World

Thanks to D.A. Pennebaker’s Documentary film Depeche Mode 101, even the band’s fans have fans.

It seems safe to say that Depeche Mode had U2’s Live at Red Rocks in mind when the band approached Pennebaker (who also made Monterey Pop and Bob Dylan’s Don’t Look Back) to make 101. The film was meant to cash in on the group’s strongest selling point – its live performances – but it also sought to capture the spirit of Depeche Mode’s following. It might not have been until after the film was made, however, that the band began to realize just how devout that following was.

The documentary – released last year, along with a double live album bearing the same name – features a busload of teenage contest winners who follow the group on the last leg of its Music For The Masses Tour. The fans dance around in the bus, fix their hair, make pit stops for beer and have conversations like this: “Where are we going today?” “Graceland, probably.” “What’s Graceland?”

Margaret Mouzakitis was one of the contest winners, and she now works for the firm that represents Depeche Mode in the U.S.. She gets only a few minutes’ worth of screen time during 101 – which, along with Anton Corbijn’s long-form video Strange – has become required viewing for all serious students of Depeche Mode. Still, when Mouzakitis travels with the group, she is regularly approached by awestruck fans who ask her, “Weren’t you on the bus?”

Theresa Conroy – a young press liaison who appears several times during the film – gets the same sort of double takes. And because she introduces herself to someone at one point in the documentary, Conroy often finds that Depeche Mode fans know her name. One such fan even tried to use it. During the recording of Violator, singer Dave Gahan got a phone call from someone claiming to be Theresa Conroy. After a few moments, Gahan laughed and said, “You’re not TC!” He banged the receiver on the table to get the impostor’s attention, then told her, “You’ve been a very naughty girl."